Sarcocystis species

Species of the intracellular, apicomplexan protozoan Sarcocystis occur in mammals, reptiles and birds around the world, including in Canada.

Summary

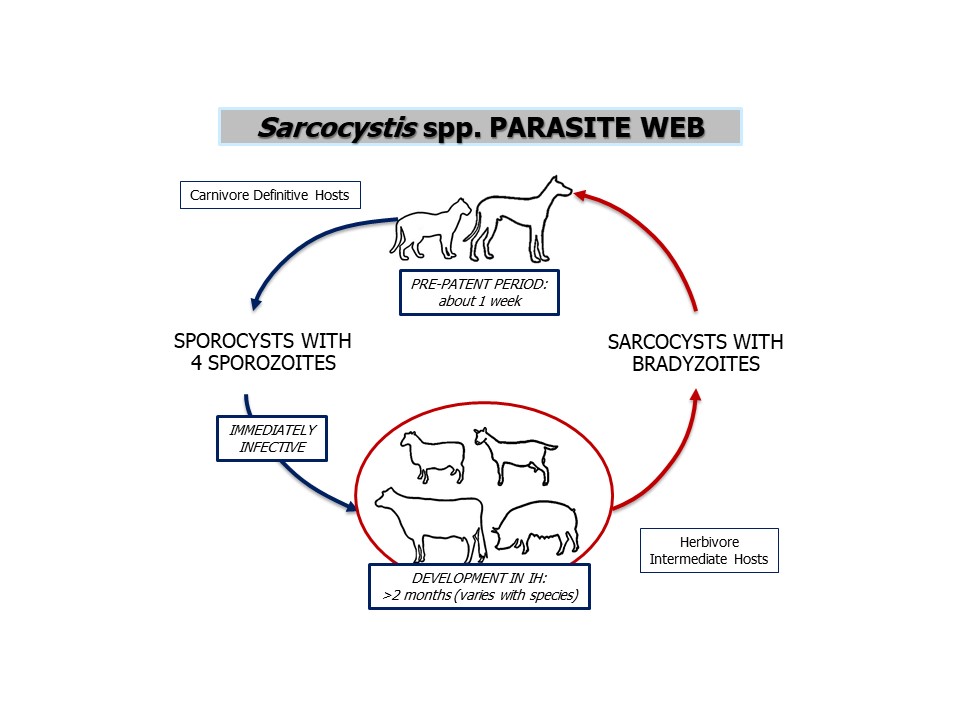

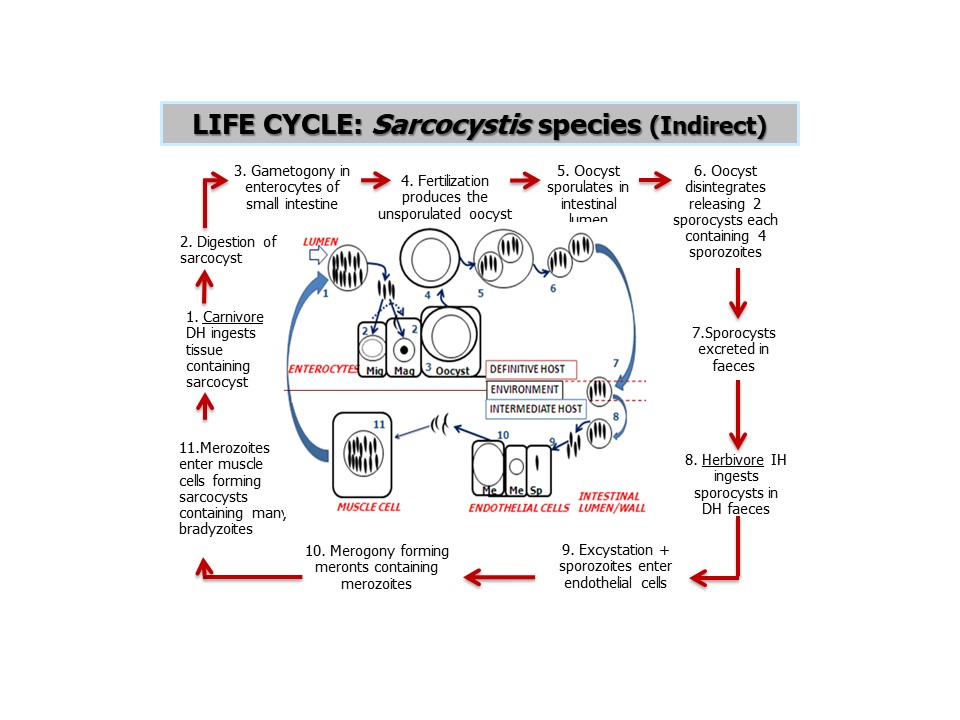

Species of the intracellular, apicomplexan protozoan Sarcocystis occur in mammals, reptiles and birds around the world, including in Canada. There are many species within the genus that circulate among specific host assemblages. The life cycle is indirect involving a carnivore definitive host - in which sexual reproduction (gametogony) and sporogony occurs inthe small intestine, and a herbivore or omnivore intermediate host, in which asexual reproduction (merogony or schizogony) occurs in the vascular endothelium and in other tissues. Carnivoredefinitive hosts pass sporocysts in the feces which are environmentally resistant and immediately infective for the intermediate hosts. Upon ingestion of sporocysts by a suitable intermediate host,sarcocysts develop in the muscle tissue. The life cycle is completed when a definitive host ingests sarcocysts in the tissues of an intermediate host through predation or scavenging. Many Sarcocystis infections, particularly in definitive hosts, are not associated with significant pathology or clinical signs. Some species, however, can cause disease in intermediate hosts, for example S. bovicanis (aka S. cruzi) and Dalmeny disease in cattle, Sarcocystis species in the CNS of sheep causing neurological signs, and S. neurona causes equine protozoal myeloencephalitis (EPM) in horses, and a wide range of vertebrate species, including dogs and cats. In dogs fed raw meat or who hunt and scavenge wildlife, it is common to detect sporocysts on routine fecal flotation, which are small, ovoid, and contain banana shaped sporozoites. Rarely, dogs can develop clinical disease (encephalitis, hepatitis, myositis) when serving as intermediate hosts for some species of Sarcocystis, for which the definitive hosts are likely wild carnivores. Treatment is seldom needed or recommended, but anticoccidial drugs have been used with some success in the treatment of horses with EPM. The species of Sarcocystis present in Canada are not zoonotic, but people (as definitive hosts) can acquire Sarcocystis from consumption of undercooked beef or pork elsewhere in the world and (as intermediate hosts), from ingestion of food or water contaminated with sporocysts from reptile feces in Asia.

Taxonomy

Phylum: Alveolata Subphylum: Apicomplexa

Class: Coccidea

Order: Eimeriida

Family: Sarcocystidae

Sarcocystis has many biological characteristics similar to other members of this family including Toxoplasma, Cystoisospora, and Neospora, but there are important differences, particularly in the life cycle. The taxonomy of species within the coccidial genus Sarcocystis is somewhat uncertain, but a number of distinct species have been identified in domestic and free-ranging animals,birds, reptiles, and people. Currently the names of many species of Sarcocystis have been revised to reflect the known definitive and intermediate hosts. Sarcocystis species tend to be somewhat host specific, especially in their definitive hosts.

Note: Our understanding of the taxonomy of helminth, arthropod, and particularly protozoan parasites is constantly evolving. The taxonomy described in wcvmlearnaboutparasites is based on Deplazes et al. eds. Parasitology in Veterinary Medicine, Wageningen Academic Publishers, 2016

Selected species and their respective definitive and intermediate hosts are listed below.

Cats - as definitive hosts

S. bovifelis (aka S. hirsuta) - cattle intermediate hosts

S. ovifelis (aka S. gigantea, S. medusiformis) - sheep intermediate hosts

S. porcifelis (aka S. suifelis) - pig intermediate hosts

Dogs - as definitive hosts

S. bovicanis (aka S. cruzi) - cattle intermediate hosts

S. ovicanis (aka S. tenella) - sheep intermediate hosts

S. fayeri - horse intermediate hosts

and many others

Dogs - as intermediate hosts

S. neurona - possum definitive host, dog as aberrant intermediate host (encephalomyelitis)

S. canis - unknown definitive host, dog as aberrant intermediate host (hepatitis)

S. caninum - unknown definitive host, dog as intermediate host (hepatitis and myositis)

S. svanai - unknown definitive host, dog as intermediate host (hepatitis and myositis)

Cattle - intermediate hosts

S. bovicanis (aka S. cruzi) - dog and coyote definitive hosts

S. bovifelis (aka S. hirsuta) - cat definitive host

S. bovihominis (aka S. hominis) - human definitive hosts

Sheep - intermediate hosts

S. ovicanis (aka S. tenella) - dog definitive hosts

S. ovifelis (aka S. gigantea, S. medusiformis) - cat definitive hosts

Horses - intermediate hosts

S. neurona - possum definitive host, horse as aberrant intermediate host

S. fayeri - dog definitive host

Pigs - intermediate hosts

S. suicanis (aka S. porcicanis, S. miescheriana) - dog, wolf and fox definitive hosts

S. porcifelis (aka S. suifelis) - cat definitive hosts

S. suihominis - human definitive hosts

People - definitive hosts (and sometimes intermediate hosts for other species)

S. bovihominis (aka S. hominis) - cattle intermediate hosts

S. suihominis - pig intermediate hosts

Morphology

The sporocysts of Sarcocystis species in the feces of definitive hosts are oval, measure 10-15 µm by 7-10 µm, and each contains four sporozoites. Identification to species is often difficult without specialized knowledge and molecular methods.

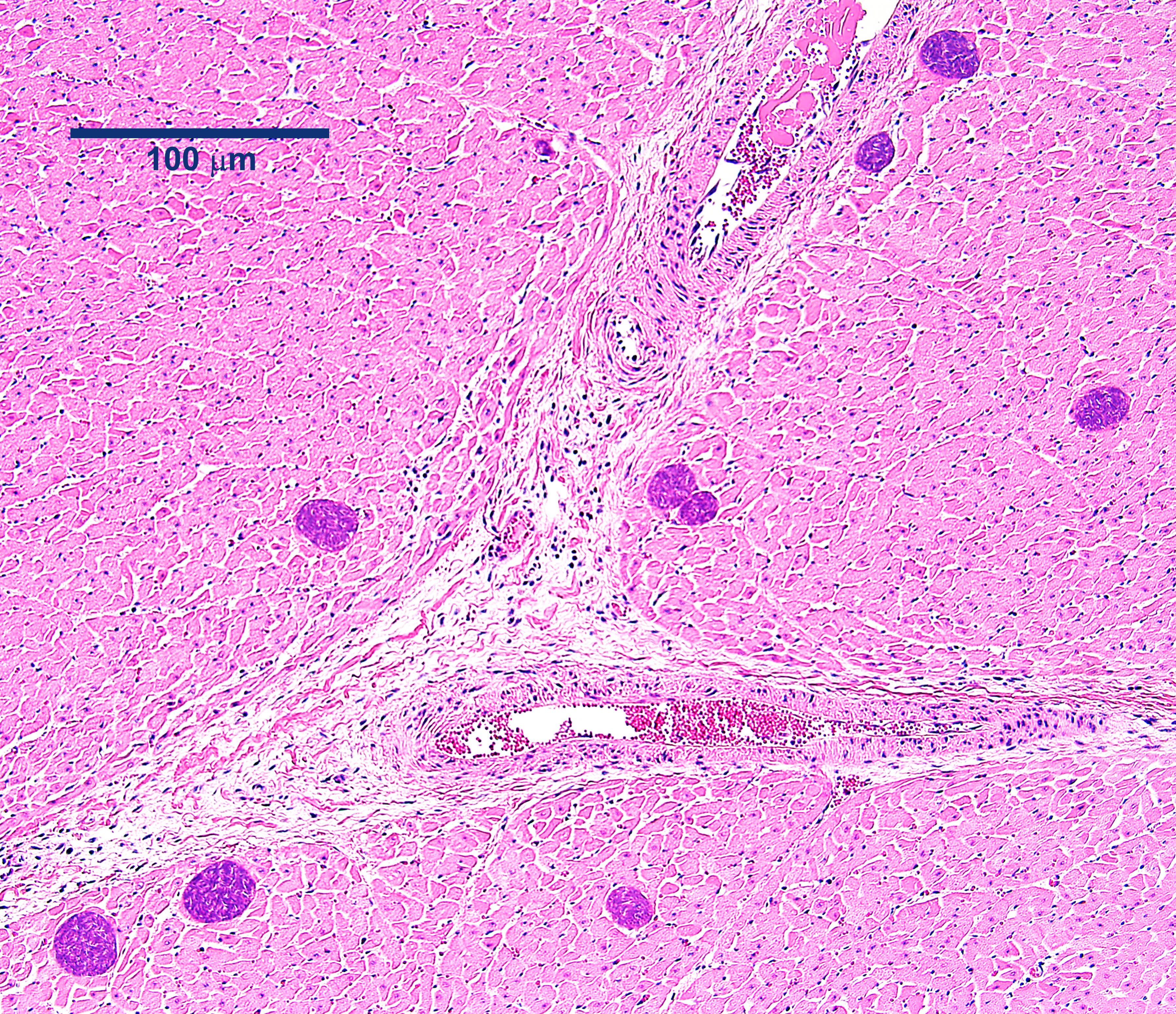

The life cycle stages of Sarcocystis in the vascular endothelium of intermediate hosts (schizonts = meronts, merozoites) can be detected only histologically, and identification to species requires molecular methods. Sarcocysts in skeletal muscle are usually linear in shape, and depending on the species and stage of development, vary in size from less then 1mm to a few centimetres in length. Sarcocysts are most commonly detected on routine histology of cardiac or skeletal muscle, especially in wildlife.

Host range and geographic distribution

Various species of Sarcocystis are found in domestic and free-ranging animals and birds around the world, including in Canada, sometimes at high prevalence and abundance . These parasites occur in cats, dogs, cattle, sheep, horses, pigs, and people. Some of these act as definitive hosts, some as intermediate hosts, and some as both. Species of Sarcocystis show some host specificity.

Life cycle - indirect

Infection of intermediate hosts is by ingestion of the sporocysts. In these hosts, the sporozoites are released and invade the intestinal mucosa, then blood vessels, where they enter the endothelial cells and undergo one or more cycles of asexual reproduction (merogony or schizogony), each resulting in the production of meronts containing merozoites. Finally the merozoites enter muscle cells and form sarcocysts containing large numbers of bradyzoites. Ingestion of the sarcocysts by definitive hosts completes the life cycle. Depending on the species, sarcocysts can be found in a range of organs and tissues, and clinical signs vary from totally asymptomatic to severe inflammation. Clinical signs can occur if meronts or sarcocysts develop in sensitive areas (for example, the central nervous system). Sometimes carnivores can also serve as intermediate hosts, developing sarcocysts in skeletal muslce, or as aberrant intermediate hosts, developing meronts in the vasculature of the liver or CNS.

Epidemiology

Pathology and clinical signs

Cats as intermediate hosts

Cats, along with many other vertebrate species, serve as intermediate hosts for S. neurona, which can, rarely, cause myeloencephalitis.

Dogs as intermediate hosts

There are rare reports of pathology and clinical signs associated with extra-intestinal development of Sarcocystis species, in the central nervous system (S. neurona), liver (S. canis), skin, and skeletal muscle (S. caninum and S. svanai).

Cattle - intermediate hosts

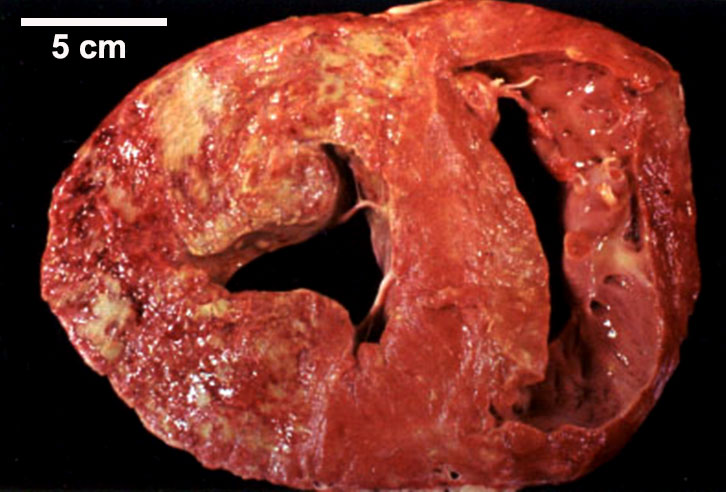

Infrequent reports of pathology and clinical signs associated with the extra-intestinal development of Sarcocystis bovicanis (aka S. cruzi), and possibly other species, in vascular endothelium in many organs and tissues. Clinical signs include fever, emaciation, anaemia and abortion, with high morbidity and some mortality. This is Dalmeny disease, first described in Dalmeny, Ontario, in 1963.

There are fairly common reports of lesions visible to the naked eye associated with the sarcocysts of S. cruzi, and possibly other species, in skeletal and cardiac muscle detected on meat inspection. This is eosinophilic myositis which is rarely if ever a cause of clinical signs, but which is commonly seen in cattle at slaughter and can lead to downgrading of the affected carcasses.

Sheep - intermediate hosts

Rare reports of generalized disease and sometimes abortions associated with the development of Sarcocystis species in vascular endothelium. Rare reports of pathology and neurological clinical signs associated with the development of sarcocysts of Sarcocystis species in the central nervous system. More common reports of Sarcocystis species in skeletal muscle, leading to carcass downgrading.

Horses - intermediate hosts

Most notably S. neurona, for which horses are an aberrant intermediate ( dead-end) host, is one of the causes of Equine Protozoal Myeloencephalitis. Other Sarcocystis species in horses do not appear to be associated with clinical disease.

Pigs - intermediate hosts

Sarcocystis suicanis is usually asymptomatic, but it can cause problems in skeletal muscle during all stages of its extra-intestinal development, leading to carcass downgrading. Sarcocystis porcifelis is believed to be relatively non-pathogenic in pigs. Sarcocystis suihominis can cause significant pathology in the liver of pigs associated with the extra-intestinal development of the parasites in vascular epithelium.

People - definitive hosts (and sometimes intermediate hosts for other species)

Sarcocystis hominis and S. suihominis are rarely if ever associated with pathology or clinical signs in their human definitive hosts, although S. suihominis appears more likely to cause transient gastrointestinal signs. When serving as intermediate hosts, species of Sarcocystis (S. lindemanni, S. nesbitti) have been associated with pathology and clinical signs caused by extra-intestinal life cycle stages of the parasite, particularly sarcocysts, in skeletal muscles .

Diagnosis

Sporocysts are relatively commonly detected on routine fecal flotation of wild carnivores, as well as dogs and cats fed raw meat or with access to consumption of wildlife carcasses. Many, but not all, species of Sarcocystis can be identified on the basis of sporocyst structure or molecular characterization, but it is beyond the capability of many diagnostic parasitology laboratories. The sarcocysts of many species are very small and cannot bedetected with the naked eye. Sarcocysts are most commonly detected as incidental findings on histology at post mortem, and immunohistochemistry can be useful for both sarcocysts and other extra-intestinal life cycle stages (meronts, merozoites). Serology is also used in some intermediate hosts (such as horses for S. neurona) but most of the antibodies currently available cannot distinguish beyond the genus Sarcocystis. PCR is increasingly useful for distinguishing among species of Sarcocystis, especially for S. neurona and other well-established species.

Treatment and control

There is very rarely a need for specific treatment of either the intestinal stages of Sarcocystis in the carnivore definitive hosts or of the extra-intestinal stages in the herbivore or omnivore intermediate hosts, except for S. neurona in horses, and sometimes other intermediate hosts, that are showing clinical signs. For dogs serving as intermediate hosts for Sarcocystis spp. who develop clinical disease (myositis, hepatitis), decoquinate may be an effective treatment. For horses with EPM, anticoccidial treatments include ponazuril, toltrazuril, and sulfa drugs with pyrimethamine. Supportive treatment can be very helpful when dealing with clinical sarcocystosis in intermediate hosts, for example Dalmeny disease in cattle.

Control of Sarcocystis depends on limiting access by intermediate hosts to sporocysts in the feces of definitive hosts (preventing carnivores from defecating on or near livestock feed), and especially not feeding definitive hosts (dogs and cats) raw, incompletely cooked, or incompletely frozen meat and other tissues from infected intermediate hosts. Most species of Sarcocystis cannot be detected with the naked eye in meat of intermediate hosts. Meat and organs from livestock and wildlife should always be thoroughly cooked or frozen to prevent transmission of Sarcocystis and other tissue dwelling coccideans, like Toxoplasma and Neospora.

Public health significance

The two species of Sarcocystis for which people are known definitive hosts are zoonoses: S. hominis - acquired by ingesting sporocysts in meat and other tissues from infected cattle, and S. suihominis - acquired by ingesting sporocysts in meat and other tissues from pigs. Rarely, people serve as intermediate hosts for Sarcocystis; most recently, cases of S. nesbitti myositis were described in tourists visiting islands in Malaysia, likely acquired from consuming sporocysts in water or food contaminated with snake feces.

References

Sykes, JE, Dubey, J.P., Lindsay, L.L., Prato, P., Lappin, M.R., Guo, L.T., Mizisin, A.P., Shelton, G.D. 2011. Severe Myositis Associated with Sarcocystis spp. Infection in 2 Dogs. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine 25 (6): 1277-1283. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-1676.2011.00828.x

J.P. Dubey, Jennifer L. Chapman, Benjamin M. Rosenthal, M. Mense, Ronald L. Schueler. 2006. Clinical Sarcocystis neurona, Sarcocystis canis, Toxoplasma gondii, and Neospora caninum infections in dogs. Veterinary Parasitology 137 (1–2): 36-49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2005.12.017.

Chapman, J., Mense, M. & Dubey, J. P. 2005. Clinical muscular sarcocystosis in a dog. J. Parasitol., 91:187–190.

Dubey, JP. et al. 2014. Sarcocystis caninum and Sarcocystis svanai n. spp. (Apicomplexa: Sarcocystidae) Associated with Severe Myositis and Hepatitis in the Domestic Dog (Canis familiaris). Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology 62(3): 307-371. https://doi.org/10.1111/jeu.12182