Ancylostoma caninum

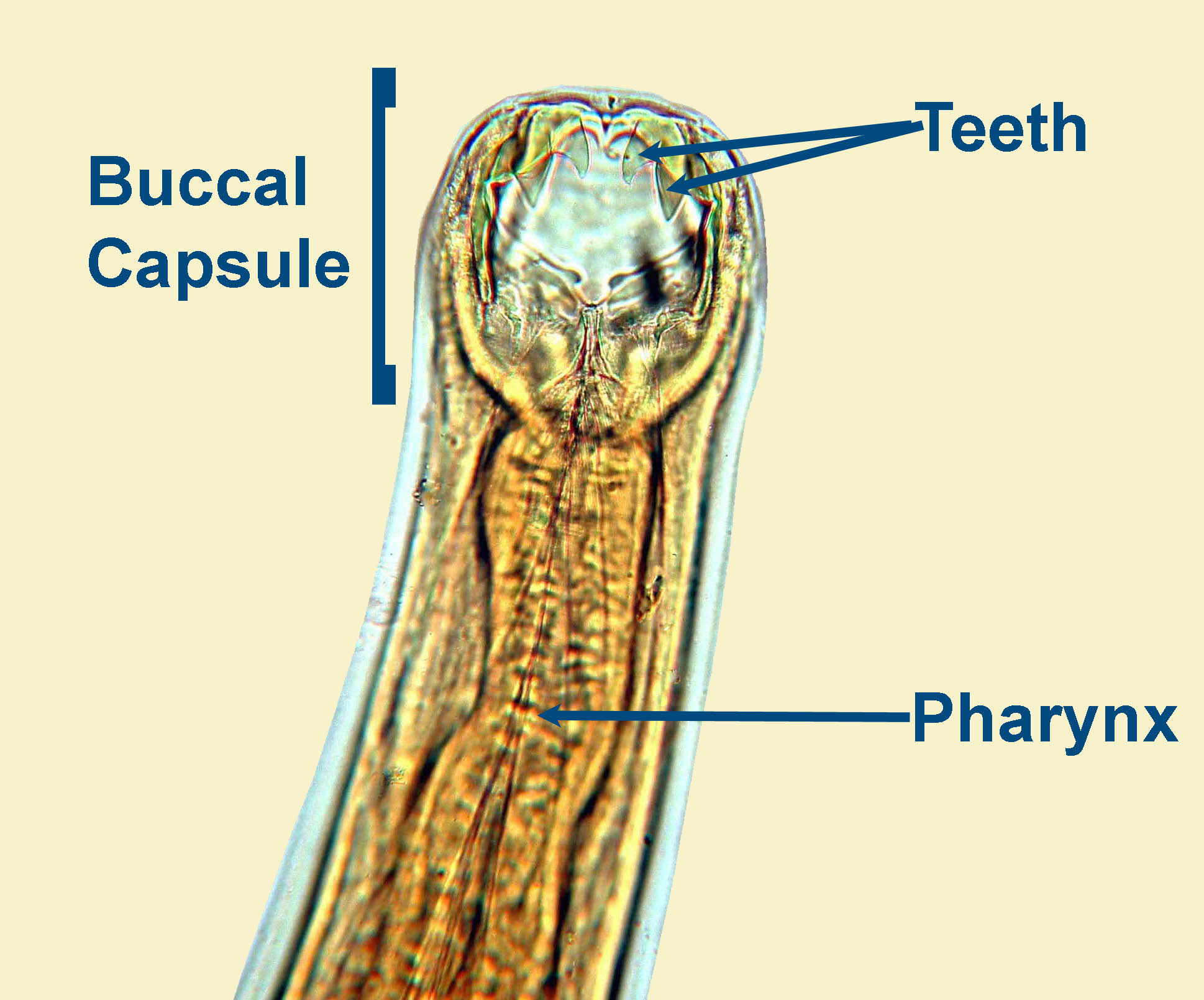

Ancylostoma caninum is a pathogenic hookworm of domestic dogs and free-ranging canids, so called because its buccal capsule is bent dorsally in the form of a "hook."

Summary

Ancylostoma caninum is a pathogenic hookworm of domestic dogs and free-ranging canids, so called because its buccal capsule is bent dorsally in the form of a "hook."

Pre-adult and adult A. caninum live in the small intestine of their canine hosts. The life cycle of the nematode is direct, although paratenic hosts may be involved. Third-stage larvae are infective and can gain access to dogs by ingestion or skin penetration. Milk from the mother is an important source of infective larvae for suckling pups (trans-mammary transmission). In young pups, the parasite can cause severe disease and death even before patent infections are detected, primarily as a result of the blood sucking activities of the pre-adults and adults in the small intestines.

In general, in dogs of all ages, pathogenicity is related to parasite burdens. Ancylostoma caninum thrives in regions where the environment is warm and humid, and where dogs are crowded and perhaps stressed. Clinical disease associated with A. caninum is rare in Canada, and is seen most often in dogs imported from regions where the parasite is endemic or that are from kennels with sub-optimal management.

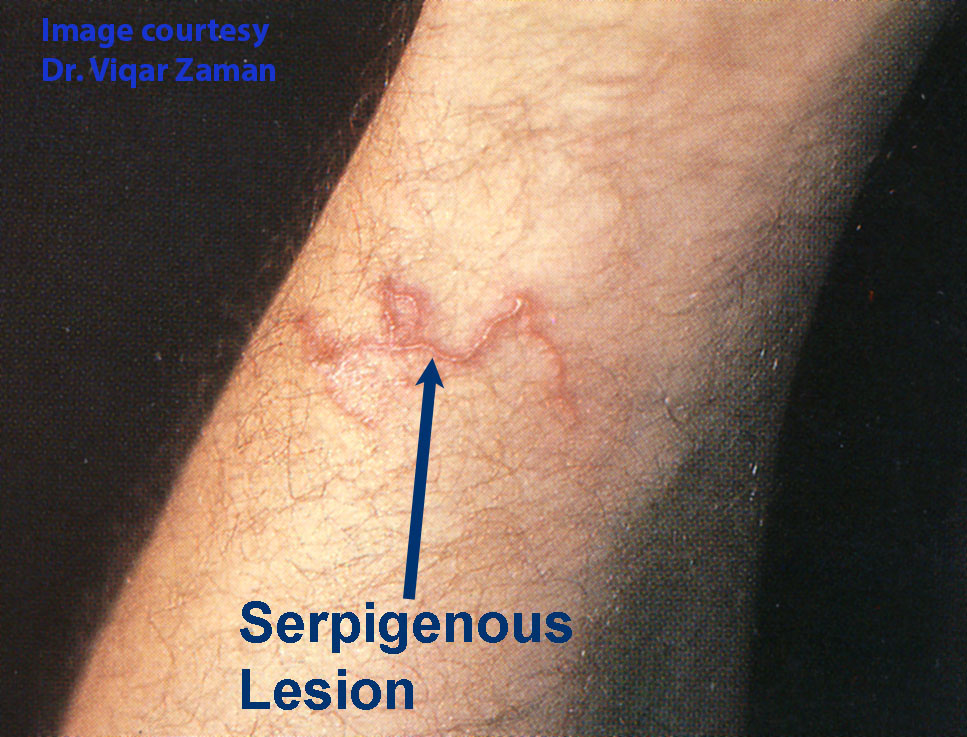

Third-stage larvae of A. caninum sometimes invade the skin of people, resulting in cutaneous larva migrans. Rarely these larvae complete their development to adults in the human intestine, where they can cause a clinically significant eosinophilic enteritis. This parasite is increasingly showing multidrug resistance in the United States, less so in Canada where it is still relatively rare.

Taxonomy

Phylum: Nematoda

Class: Secernentea

Order: Strongylida

Superfamily: Ancylostomatoidea Family: Ancylostomatidae

Ancylostoma caninum is one of the hookworms of dogs. It is related to the other hookworms of dogs (A. braziliense, A. ceylanicum and Uncinaria stenocephala), and to the hookworms of cats (A. tubaeforme and A. ceylanicum) and of people (A. duodenale and Necator americanus). The adult parasites and the eggs of these various hookworm species are morphologically similar, and the life cycles and pathology share many features. Some species of hookworm are able to infect several species of host, including people.

Morphology

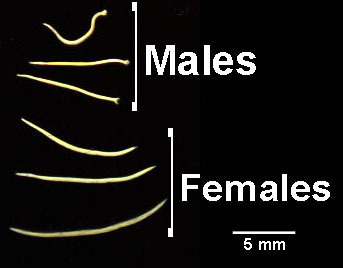

Adult A. caninum are up to approximately 12 mm (males) and 15 mm (females) in length and are easily visible to the naked eye. Adults have a prominent buccal capsule, the opening into which has three pointed teeth on each side of its ventral aspect. The exact structure of the buccal capsule is important in distinguishing between the various hookworm species.

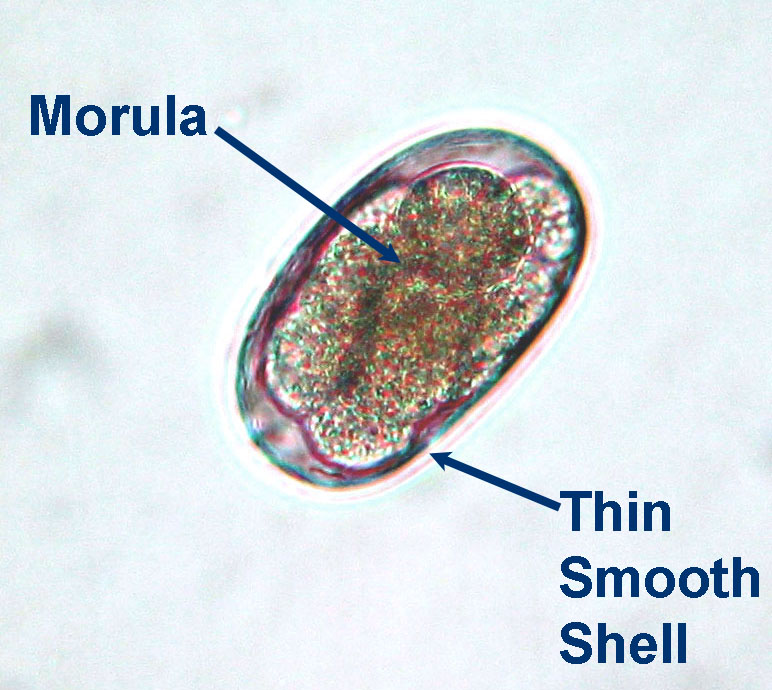

Eggs measure approximately 55 to 75 µm by 35 to 45 µm, and are oval with a thin smooth shell (typical "stringyle-type" egg). When freshly passed, each egg contains a few cells grouped together – a “morula”. Eggs of A. caninum are slightly smaller than those of U. stenocephala, and this is the basis for differentiation of the two from fecal examinations.

Host Range and Geographic Distribution

Life cycle

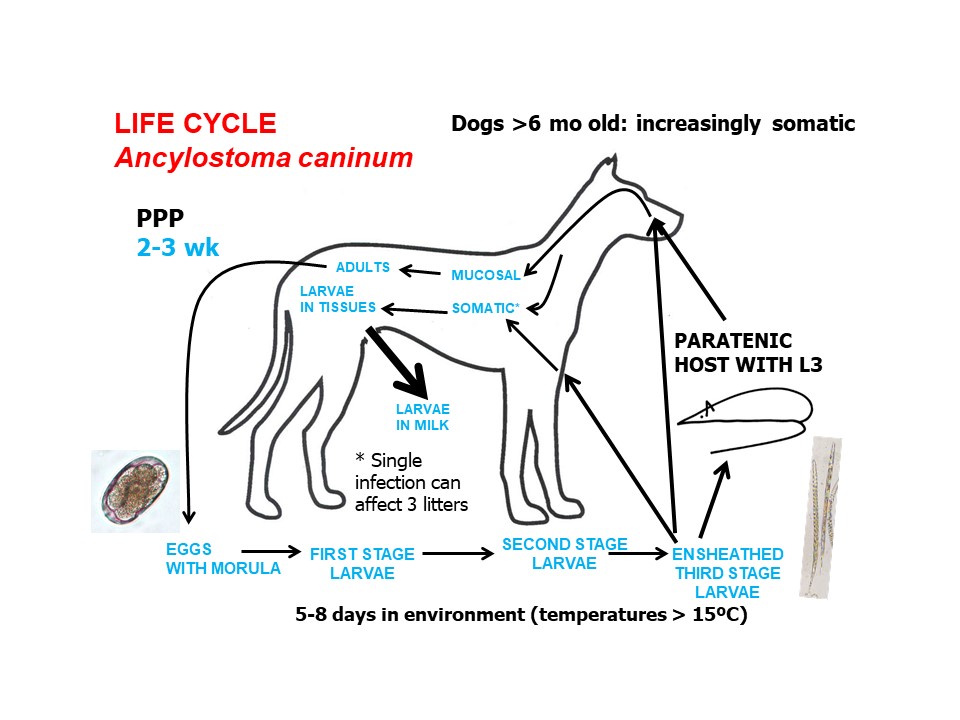

Adult A. caninum live in the small intestine. Eggs are passed in feces. In the environment, a first-stage larva develops within each egg. The larva then hatches and develops to the infective third stage - within a 5-8 days under ideal conditions (temperatures greater than 15 C). Dogs are infected when larvae are ingested or penetrate the skin.

Following ingestion, in pups less than 6 months of age, most larvae follow a mucosal migration. In young or naive dogs, infective larvae that penetrate the skin follow a semi-tracheal migration (subcutaneous tissues to vasculature to right heart to lungs to trachea to pharynx to GI tract). The pre-patent period is 2-3 weeks, shorter in pups. In dogs older than 6 months of age, larvae acquired through ingestion of through the skin increasingly undergo somatic migration (following ingestion, GI tract to portal vessels to liver to right heart to lungs to left heart to somatic tissue; following skin penetreation, subcutaneous tissues to vasculature to right heart to lungs to left heart to somatic tissue.

In female dogs, these larvae in the tissues can become mobilized during late pregnancy and travel to the mammary glands where they infect nursing pups through the colostrum and milk for at least the first three weeks of lactation. This trans-mammary transmission is the most important source of exposure for young pups, in which third stage larvae ingested in milk undergo a mucosal migration. A single massive infection of a breeding female may infect multiple litters.

Finally, dogs may become infected by ingestion of third stage larvae in a range of paratenic hosts.

Life Cycle: Ancylostoma caninum

Epidemiology

Pathology and clinical signs

Infective larvae of A. caninum penetrating the skin may cause localized lesions – cutaneous larva migrans - which is most common in areas of the body in contact with the ground (ventral dermatitis). Pre-adults and adults in the intestine suck blood, which in heavy infections, can cause severe even fatal anaemia especiallyl in untreated young pups. The pre-adult and adult parasites attach to the intestinal mucosa using their buccal capsule, abrade the host tissues with their teeth, and secrete an anti-coagulant. They suck blood very rapidly and they graze – they feed for a while in one site, then detach leaving the site bleeding, then re-attach in a new location.

Clinical signs of hookworm disease are primarily those associated with blood loss anemia although migrating larvae can cause respirtory signs in heavely infected pups. Infection with A. caninum in dogs is more common than is clinical disease, and some adult dogs can harbour small or moderate burdens of A. caninum with few obvious adverse effects. In dogs of any age, other concurrent disease may exacerbate the effects of hookworm infection.

Diagnosis

Treatment and Control

There are several products approved for use in dogs in Canada for the life cycle stages of A. caninum in the intestinal lumen. For clinically anemic, very young pups treatment has to be aggressive and supplemented by supportive measures to correct, or at least ameliorate, the blood loss. Fenbendazole and macrocyclic lactones, given to a pregnant or lactating female, help to prevent pre-natal and trans-mammary transmission. These are extra-label uses for these drugs.

Following treatment which removes adult nematodes from the intestine, somatic larvae may repopulate the intestine, leading to paradoxical surges in egg shedding approximately 2 weeks following treatment (larval leak). This cannot be easily distinguished from rapid re-infection from the environment or, increasingly, multi-drug resistance, especially in dogs from the USA. In light of increasing anthelmintic resistance, consideration should be given to treating only those adult dogs with clinical anemia due to hookworms or concurrent disease which may cause them to decompensate, as well as breeding females.

Public health significance