Baylisascaris procyonis

Baylisascaris procyonis is a small-intestinal nematode of raccoons in North and Central America, including Canada

Summary

Taxonomy

Phylum: Nematoda

Class: Secernentea

Order: Ascaridida

Superfamily: Ascaridoidea

Family: Ascarididae

Baylisascaris procyonis is an ascarid nematode related to Ascaris (pigs), Parascaris (horses), Toxocara and Toxascaris (dogs and cats), and shares many features with these genera. Closely related species include, B. columnaris in skunks, B. transfugia in bears, and B. devosi in wolverines.

Note: Our understanding of the taxonomy of parasites is constantly evolving. The taxonomy described in wcvmlearnaboutparasites is based on Deplazes et al. eds. Parasitology in Veterinary Medicine, Wageningen Academic Publishers, 2016

Morphology

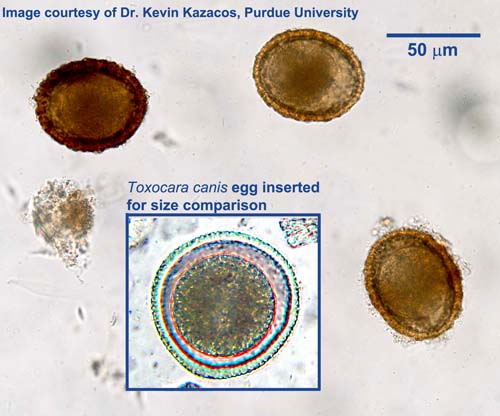

Adult B. procyonis are large, fleshy worms, up to approximately 20 cm in length. Mature females are larger than mature males. Eggs are ellipsoidal, approximately 75µm by 60µm, with a thick, rough, granular shell. They closely resemble the eggs of Toxocara canis, which are sub-spherical but larger, measuring approximately 90µm by 80µm, and have a pitted shell similar to a golf ball. The larvae developing in the paratenic hosts are relatively large, reaching 1-2 mm in length.

Host Range and Geographic Distribution

Life cycle

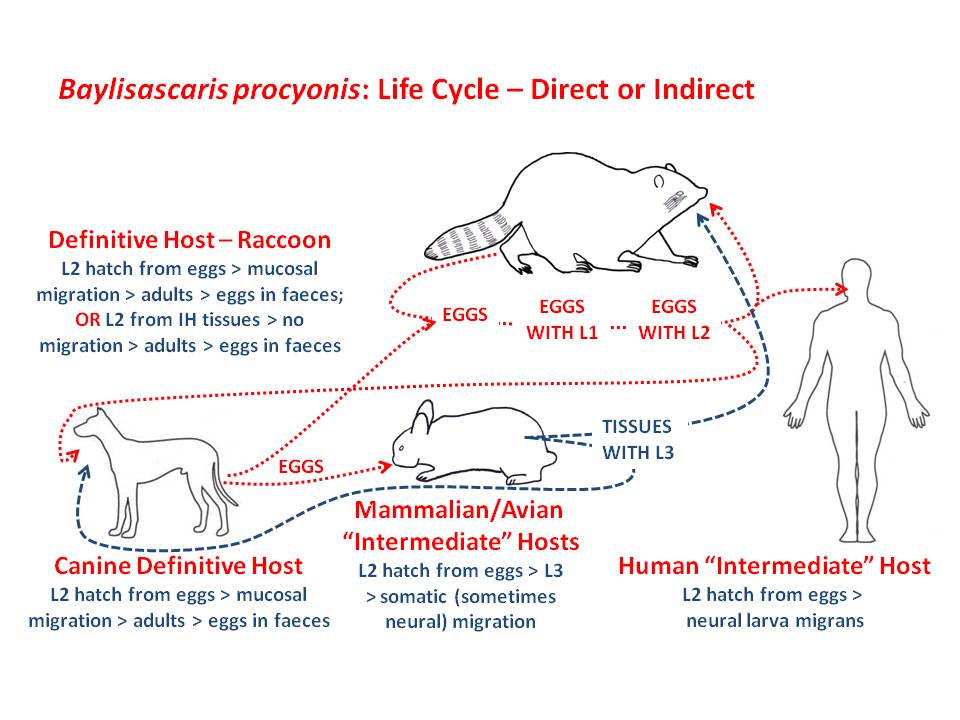

Raccoons are the definitive hosts for B. procyonis, but dogs can (rarely) also support the development of adult parasites and patent infections. In the definitive hosts the adult parasites are found in the small intestine, and parasite numbers tend to be higher in young animals. Adult female parasites can produce large numbers of eggs (up to 250,000 eggs per gram) which are passed in the feces. In the environment, larvae develop within the eggs to the third-stage larvae, which is the infective stage for definitive and paratenic hosts. Under ideal conditions, this egg development takes approximately two weeks. In young raccoons, following ingestion, the eggs hatch and the larvae released undergo a mucosal migration in the small intestine. The prepatent period is approximately two months. In adult raccoons, infection by ingestion of third-stage larvae in the tissues of paratenic hosts is more common, and the prepatent period is approximately one month. Dogs can serve as paratenic hosts following ingestion of infective B. procyonis eggs, with larvae undergoing a somatic migration and become encapsulated in a variety of tissues. In many paratenic host species, migrating larvae invade the central nervous system and cause severe pathology and clinical signs. Rarely, in dogs ingesting larvated eggs in the environment or larvae in other paratenic hosts, the larvae undergo a mucosal migration and develop to adult nematodes in the intestine of the dog.

People serve as paratenic hosts in the life cycle, in which larvae in the central nervous system can cause serious, even fatal clinical problems.

Epidemiology

Prevalence and intensity of B. procyonis are higher in young raccoons less than one year old than in older animals. Young raccoons are infected primarily by ingestion of infective eggs from their immediate environment - including the haircoat of their mothers and the dens in which they live, while in older animals ingestion of paratenic hosts is more important. Raccoons tend to have designated locations for defaecation - so-called "raccoon latrines". The latrines are most often found at the base of trees or on large logs, but they also occur in association with buildings. Given the high levels of egg production by B. procyonis and the longevity of the eggs in the environment (years, given suitable conditions), these latrines and their immediate surroundings can become very heavily contaminated and serve as a major source of B. procyonis infection.

The latrines are attractive to many species of paratenic hosts, which visit the latrines to recover undigested plant material, especially seeds, from the feces of the raccoons. Most infections in dogs and in people are likely acquired from contact with these latrines or with other areas contaminated with raccoon faeces, although dogs could also ingest paratenic hosts. To date,human and dog infections are thought to have been acquired as a result of environmental contamination with raccoon feces.

It is important to note that eggs are not immediately infective and therefore the real risk lies in ingestion of larvated eggs in older feces in heavily contaminated environments.

Pathology and Clinical Signs

Baylisascaris procyonis in raccoons is rarely if ever associated with clinical signs unless present in very large numbers in the intestine. In dogs, the adult parasites in the intestines do not usually cause clinical signs, but migrating larvae have been associated with severe, even fatal neurological disease.

In paratenic hosts, neural larval migrans (NLM) is relatively common, and has been observed in more than 100 species of mammals and birds.

In the paratenic hosts, the severity and nature of the clinical signs depends on the number of larvae reaching the central nervous system, the migration routes followed in the CNS, the size attained by the larvae (can be 1-2 mm in length), and the severity of the tissue damage. Death is a common result of B. procyonis in these hosts.

Diagnosis

In raccoons and dogs, patent infections with B. procyonis can be diagnosed by recovering and identifying eggs in fecal samples using an appropriate centrifugation-flotation technique. The eggs of B. procyonis (ellipsoidal, approximately 75µm by 60µm, with a thick, rough, granular shell) are similar, but not identical, to those of Toxocara canis (sub-spherical but larger, measuring approximately 90µm by 80µm, and have a pitted shell similar to a golf ball).

Newer coproantigen and coproPCR tests can provide definitive diagnosis, although it is important to consider coprophagia with these methods as well. It is possible that some dogs with apparently patent infections with B. procyonis have simply ingested fresh raccoon faeces containing non-larvated, non-infective eggs that pass through the GI system. Likewise, detection of larvated eggs of B. procyonis in fresh fecal samples from a dog can be attributed to coprophagia of raccoon feces; however, this does indicate that the dog is at risk of developing NLM and of mechanically passing eggs infective for people in its stool.

In dogs serving as paratenic hosts, history (including exposure to old raccoon feces) and clinical signs are important in the diagnosis of symptomatic B. procyonis infection. Definitive diagnosis depends on the detection and identification of the larvae in various tissues at post-mortem.

For cases in people, an ELISA available in the USA can detect antibodies in serum and in cerebro-spinal fluid.

Treatment and Control

Minimizing the risks of exposure of dogs and people to B. procyonis depends on awareness of the issue, making inhabited buildings and land inhospitable to them and, if this is not practical, on limiting contact between children and dogs and raccoon habitat, especially the latrines.

Public health significance

The major public health significance of Baylisascaris procyonis of raccoons is as a cause of larva migrans, including ocular and visceral and neural larva migrans (NLM), in people.

This disease is still relatively uncommon in North America

Most of the cases reported have been in children less than five years old with a history of pica and/or geophagia and exposure to raccoons and/or raccoon habitat. Baylisascaris NLM in people is a very serious disease, and those who survive have life-long neurological deficits. Compared to larval migrans caused by Toxocara canis, larvae of B. procyonis are larger and more neurotropic. Dogs with patent B. procyonis infections are also a public health threat, as well as through mechanical passage of larvated eggs from ingesting raccoon feces.

Awareness of the issue of B. procyonis and larva migrans is critical to the prevention of human infections, especially in situations where there is the potential for exposure of people, particularly children, and pets to raccoon habitats, especially the latrines. Wildlife rehabilitators should be aware of the high prevalence of this serious zoonosis in young raccoons, and there is serological evidence that exposure may be common in this human population