Ctenocephalides (felis) felis (cat flea) Ctenocephalides (felis) canis (dog flea)

Fleas of the genus Ctenocephalides occur on dogs and cats around the world.

Summary

Dog and cat fleas, and fleas from other hosts, will sometimes bite people, and can transmit bacterial pathogens

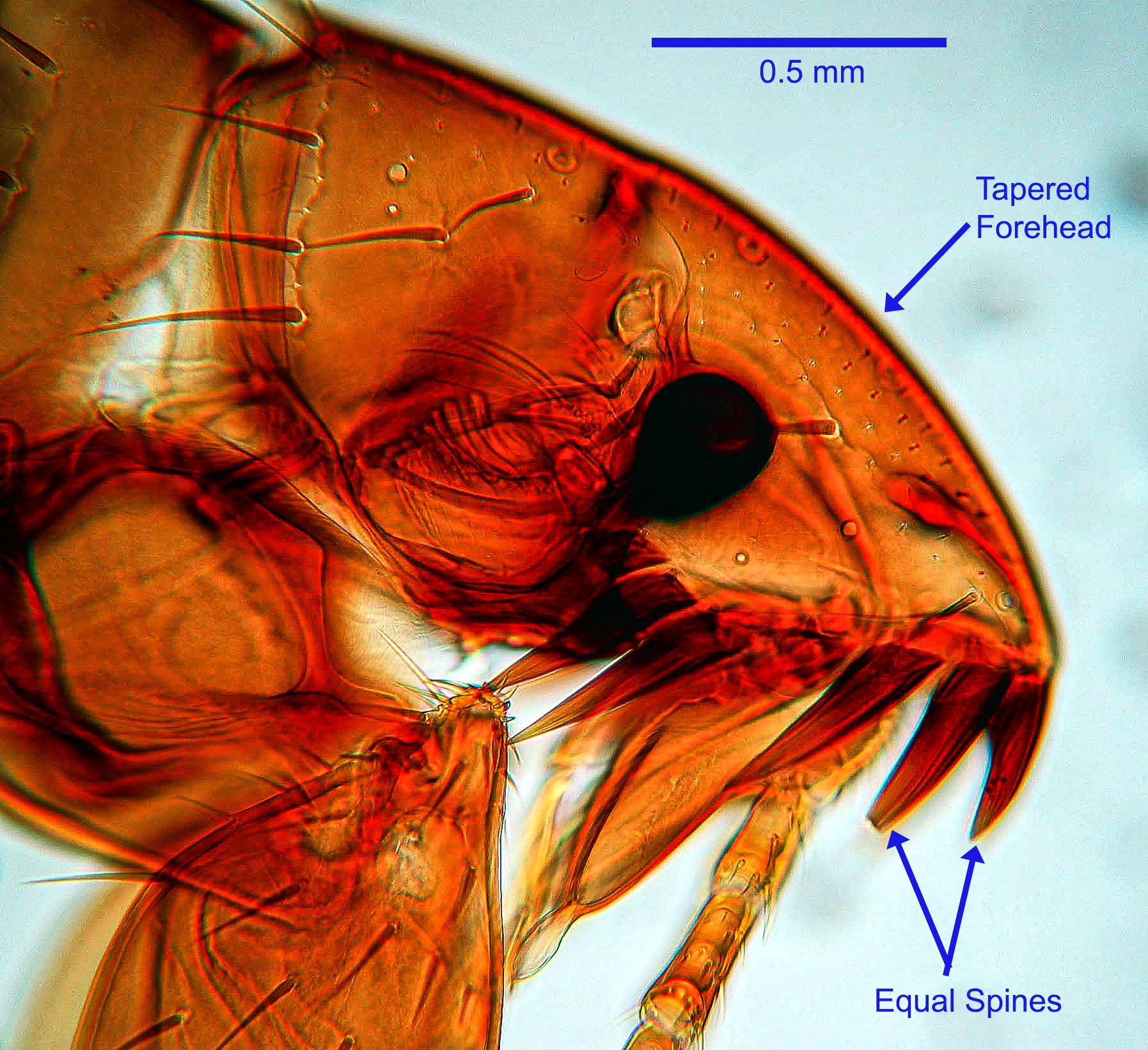

C. felis: Head

Taxonomy

Phylum: Arthropoda

Class: Insecta

Order: Diptera

Suborder: Siphonaptera

The Order Siphonaptera includes all fleas. Most fleas of veterinary importance on mammals in Canada are in the Family Pulicidae (including Ctenocephalides, Pulex, and Xenopsylla). Fleas in the family Ceratophyllidae tend to primarily feed on birds, although they are not particularly host specific and will bite mammals. Family Tungidae is only an issue in the tropics.

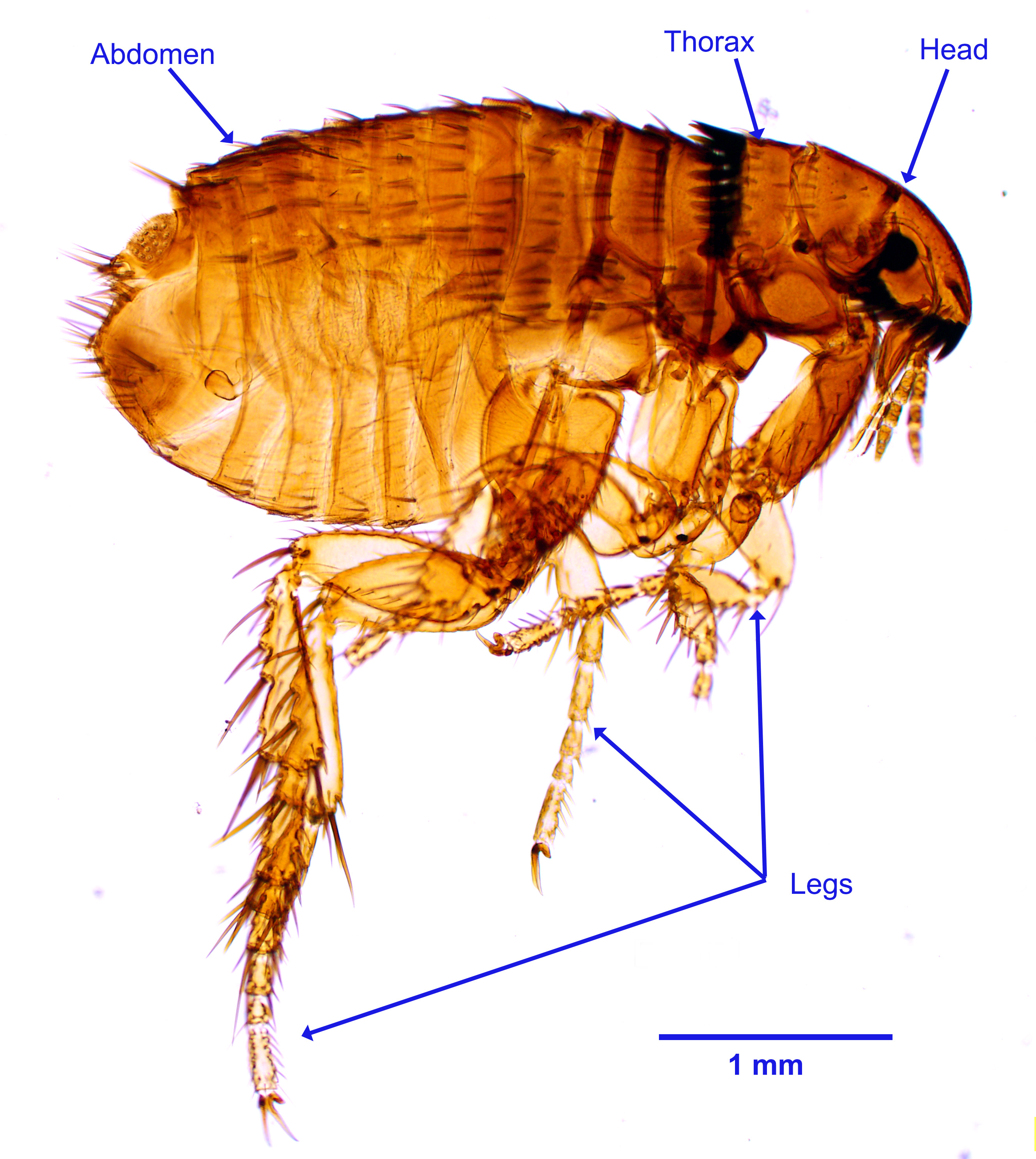

Morphology

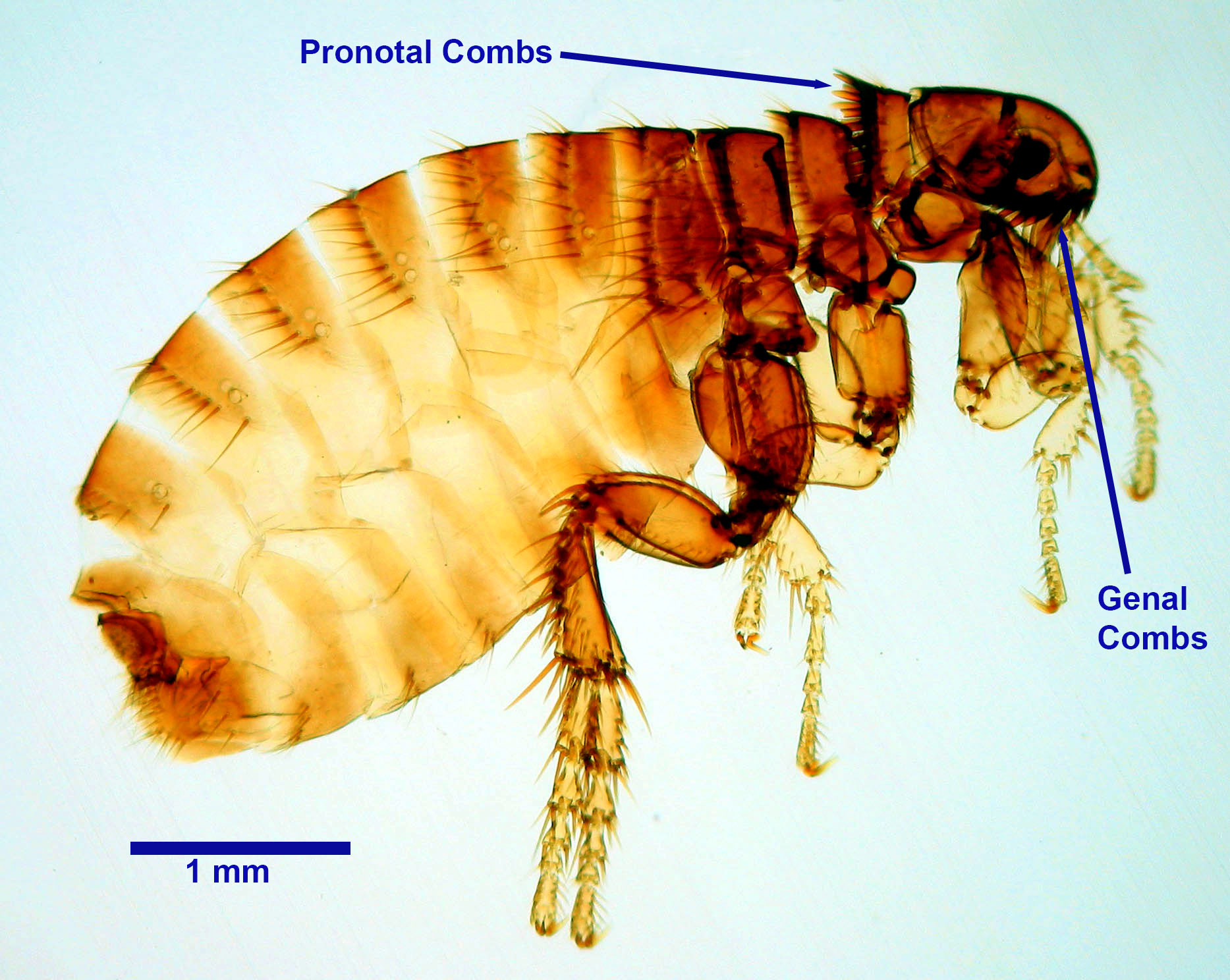

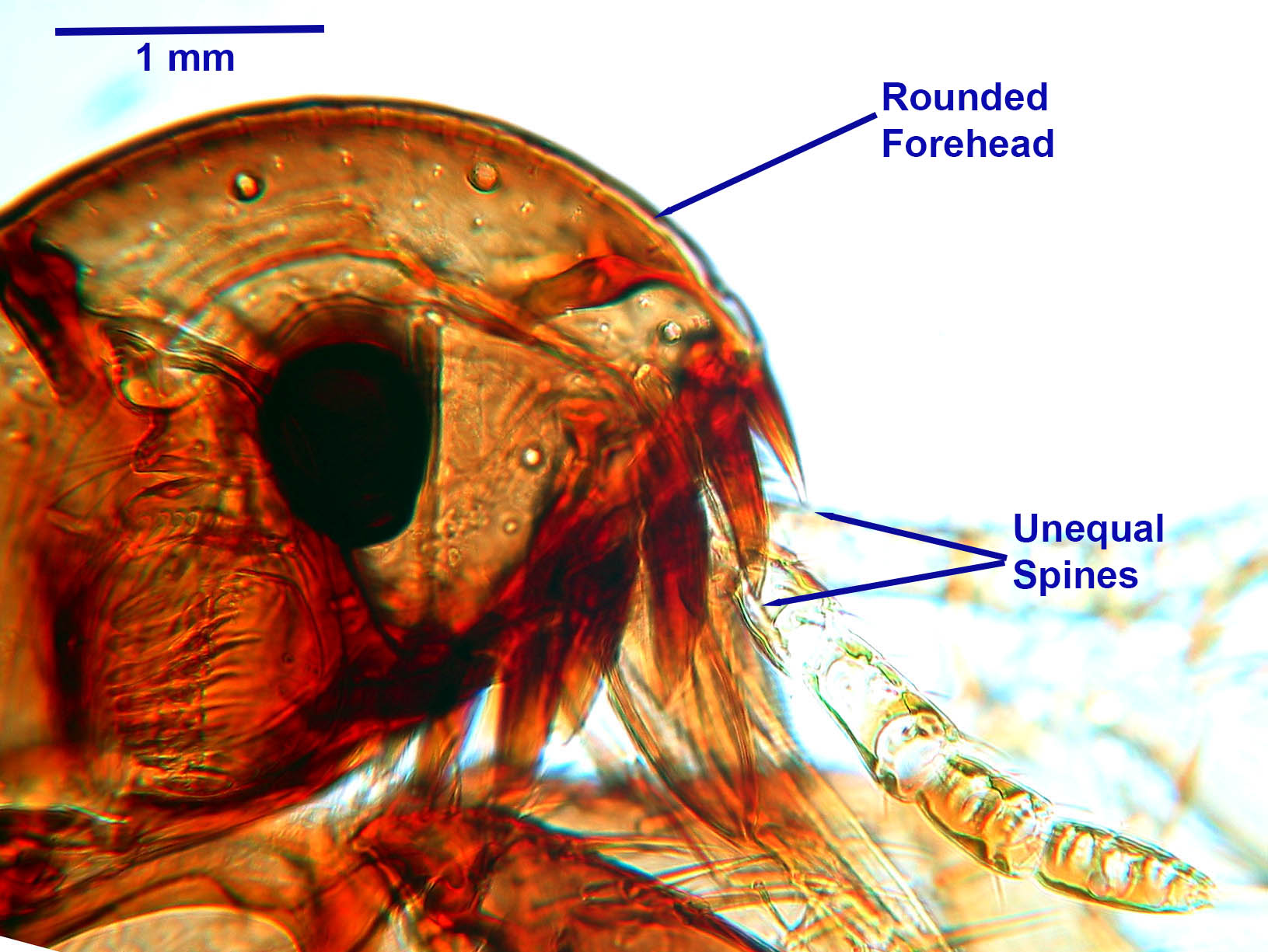

Adult fleas are small (measuring up to a few mm in length), laterally flattened and with six legs but no wings. The caudal pair of legs are longer and more substantial than the others and are important for jumping. The head of a flea has a convex lateral profile, and depending on the species, may have ventral genal and/or caudal pronotal combs that are important in identification. The common human flea – Pulex irritans – has no combs. The lateral profile head of the cat flea cat flea gently slopes, whereas that of the dog flea is more convex.

Adult fleas are small (measuring up to a few mm in length), laterally flattened and with six legs but no wings. The caudal pair of legs are longer and more substantial than the others and are important for jumping. The head of a flea has a convex lateral profile, and depending on the species, may have ventral genal and/or caudal pronotal combs that are important in identification. The common human flea – Pulex irritans – has no combs. The lateral profile head of the cat flea cat flea gently slopes, whereas that of the dog flea is more convex.Flea eggs are pearly white and oval, measuring approximately 0.5 mm in length. The larval stages of fleas are whitish yellow, segmented and caterpillar-like, with fine bristles at the caudal margin of each segment. Third-stage larvae may be up to approximately 1 cm in length. Flea pupae when first formed are up to approximately 3 mm in length and are covered by a thin, loosely-woven cocoon, to which debris from the environment often adheres.

Host range and geographic distribution

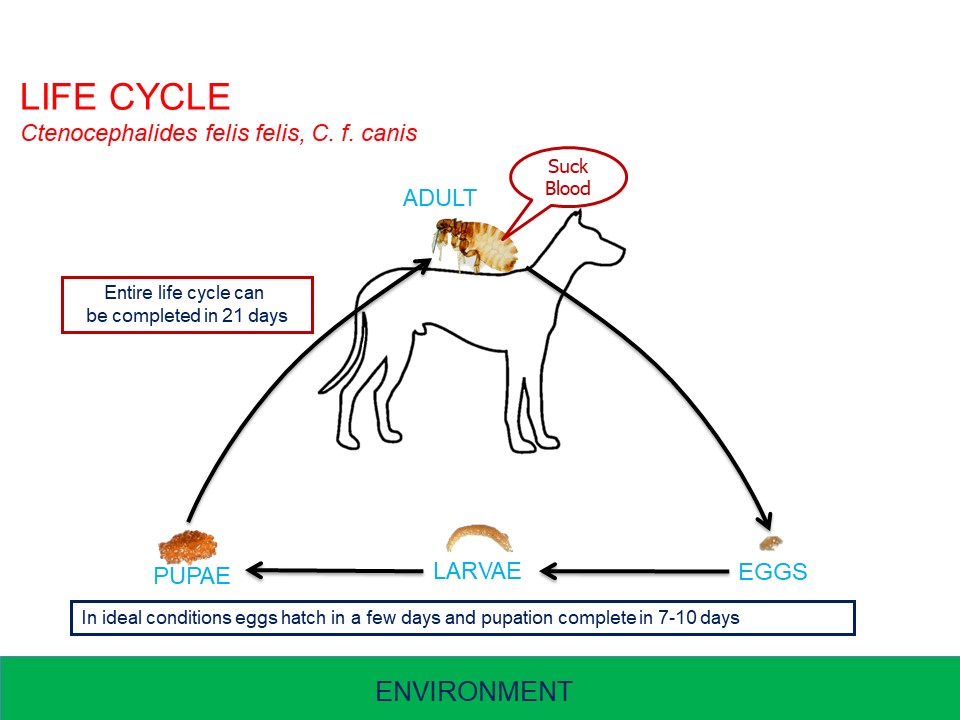

Life cycle - direct

Under suitable environmental conditions (see below), a larva develops within each egg, which then hatches. The larvae move away from light (negative phototaxis) and towards the deeper layers of their environment (positive geotaxis). Flea larvae are highly mobile and are able to move up to 40 cm on a suitable substrate. They feed on blood-rich fecal material from the adult fleas, on non-fertile eggs, and on each other (!), and moult through three larval stages. The larva then pupates, forming a sticky cocoon to which debris becomes rapidly attached. Under ideal conditions, after approximately one week, the pupa develops into an immature adult which remains within the pupae. Emergence of the immature flea depends on physical pressure, warm temperatures and carbon dioxide, as occur when a host steps on or close to the cocoon. In the absence of these stimuli, the immature flea can survive in the cocoon for up to four or five months. Once emerged, the adult flea must find a suitable host within a couple of weeks or it will not survive. The newly-emerged adults are attracted to their hosts by body heat, movement and carbon dioxide. Once on the host, the adults usually begin to blood feed immediately, and the females mate and start egg laying within a couple of days.

The rates of development of the free-living life cycle stages of fleas require temperatures between 4C and 35C and relative humidity greater than 50%. Under ideal conditions (temperature approximately 25C, relative humidity approximately 75%), eggs will hatch in a few days, pupation will be completed in 7 to 10 days and the whole life cycle can be completed within 3 weeks. Flea larvae are very susceptible to high temperatures and to desiccation, but immature adults withing the pupa can survive for several months, even when relatively desiccated.

Epidemiology

Probably the key feature is that most of the flea population is composed of immature stages in the environment. Individual animals can, however, harbour large numbers of adult fleas, and although grooming, especially by cats, may remove many of these, the infested animal may still be a formidable source of environmental contamination. In the environment immature adults present in the pupae can survive for months until they are stimulated to emerge. Thus pets may become re-infested from seasonal dwellings even after months of abscence.

Fleas have low host specificity adn therefore other animals and birds, and their burrows and nests, can serve as sources of infestation for dogs and cats with wildlife fleas (Pulex, Xenopsylla, Ceratophyllus) and, perhaps, with C. felis.

In warmer parts of the world, for example the southern US and southern coastal BC, the various life cycle stages of fleas can survive in the environment year-round. In cooler areas, including most of western Canada, cat and dog fleas are uncommon and it is not entirely clear how fleas survive from year to year. Some may accomplish this as immature stages in a presumably protected environment; others may persist on “carrier” hosts.

Pathology and clinical signs

Adult fleas, especially females, blood feed. This can cause severe irritation and lead to blood-loss anaemia, particularly in heavily infested young animals that are otherwise stressed. It has been estimated that 72 adult female fleas can remove 1 ml of blood per day. Additionally, flea dirts (feces) may adversely affect hair coat appearance. The severity of the effects of fleas depends on the number present on the animal, the host’s tolerance of skin irritation, and the presence or absence of hypersensitivity to antigens in the saliva. The grooming activity of cats can result in notable reductions in adult flea populations on the animals.

Flea dirt

Dogs and cats, even those with apparently only a few fleas, may develop a hypersensitivity reaction to antigens in flea saliva - Fleabite Allergic Dermatitis (FAD). This is characterised by severe pruritus, especially along the caudal back, the caudal aspects of the hind legs, and the ventral abdomen, and by the results of the animal’s attempts to relieve the itching by licking, scratching and chewing. It may be very difficult to find fleas on a dog or cat with FAD, even those with severe lesions, in some cases because the fleas are removed by frequent self-grooming. The lesions and clinical signs can persist because they are associated with hypersensitivity, which is not dependent on the presence of the fleas.

Fleas from dogs and cats may feed on other hosts, and on people, sometimes causing severe irritation, and fleas from these hosts may feed on dogs and cats, with similar results.

Fleas, including C. felis felis, are important in the US as vectors of feline, and possibly human plague (both caused by Yersinia pestis), of murine typhus (caused by Rickettsia typhi) and, across North America, of the nematode Dipetalonema reconditum and the cestode Dipylidium caninum. Recent research indicates that C. felis felis can also transmit Bartonella henselae (the cause of cat-scratch fever) and Feline Leukemia Virus among cats.

Diagnosis

Flea Allergic Dermatitis (FAD) may mimic other allegies, and even sarcoptic mange, and can be confirmed by intradermal testing for hypersensitivity. Due to the intense pruritus and the difficulty in detection, animals suspected of FAD should be treated immediately and not await detection of fleas.

Treatment and control

There are several adulticides (imidacloprid - a neonicotinoid, selamectin, and isoxazolines) approved for use in dogs and cats in Canada. Adulticides are the initial treatment of choice for FAD cases. There are also life cycle disruptors approved in Canada (juvenile-hormone analogs i.e. pyriproxyfen and methoprene and chitin synthesis inhibitors i.e. lufenuron) which do not kill the adults, but which interfere with the fleas’ natural development cycle and will more gradually eliminate the flea population within a home or kennel. There are a range of topical and oral products, and should be administered to all in-contact dogs and cats. Most products require repeated monthly administration during the warmer seasons of the year, and even year round in warm and wet regions. There are also several products approved in Canada for use as premise treatments, but these are generally only indicated in households with severely allergic pets or with heavy infestationsThere is no evidence to date that fleas have developed significant resistance to any of the commonly used products, but care is required to maintain this situation.

In addition, over-use of flea products (such as neonicotinoids) may have environmental impacts on harmless and even beneficial insects.

Note that cat and dog fleas are intermediate hosts for the tapeworm Dipylidium caninum, and animals infected with fleas should be monitored for this tapeworm, and treated with an appropriate cestocide if indicated.

Public health significance

Fleas are not very host specific, and animal and bird fleas will readily feed on people, even if they do not usually proceed to egg laying. Dogs or cats that have large burdens of fleas are particularly likely to pass them on to people.

Although rare, fleas can transmit pathogens to people, including Bartonella and Rickettsia spp. bacteria, and in endemic regions (such as southern Saskatchewan), rodent fleas can transmit Yersinia pestis (plague).

References

Blagburn BL et al. (2009) Biology, treatment and control of flea and tick infestations. Veterinary Clinics of North America Small Animal Practice 39: 1173-1200.

Perrins N et al. (2007) Recent advances in flea control. In Practice 29: 202-207.