Cuterebra species — rabbit bot

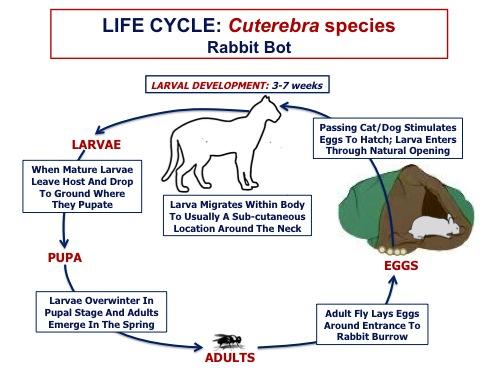

Adults of the dipteran (fly) genus Cuterebra are free-living. Larvae are found under the skin of various hosts, generally rodents but occasionally dogs and cats.

Summary

Taxonomy

Phylum: Arthropoda

Class: Insecta

Order: Diptera

Sub-order: Brachycera

Family: Oestridae

Other oestrid flies of veterinary importance include Hypoderma (warbles in cattle), Gasterophilus (bots in horses) and Oestrus (bots in sheep).

Note: Our understanding of the taxonomy of parasites is constantly evolving. The taxonomy described in wcvmlearnaboutparasites is based on Deplazes et al. eds. Parasitology in Veterinary Medicine, Wageningen Academic Publishers, 2016t

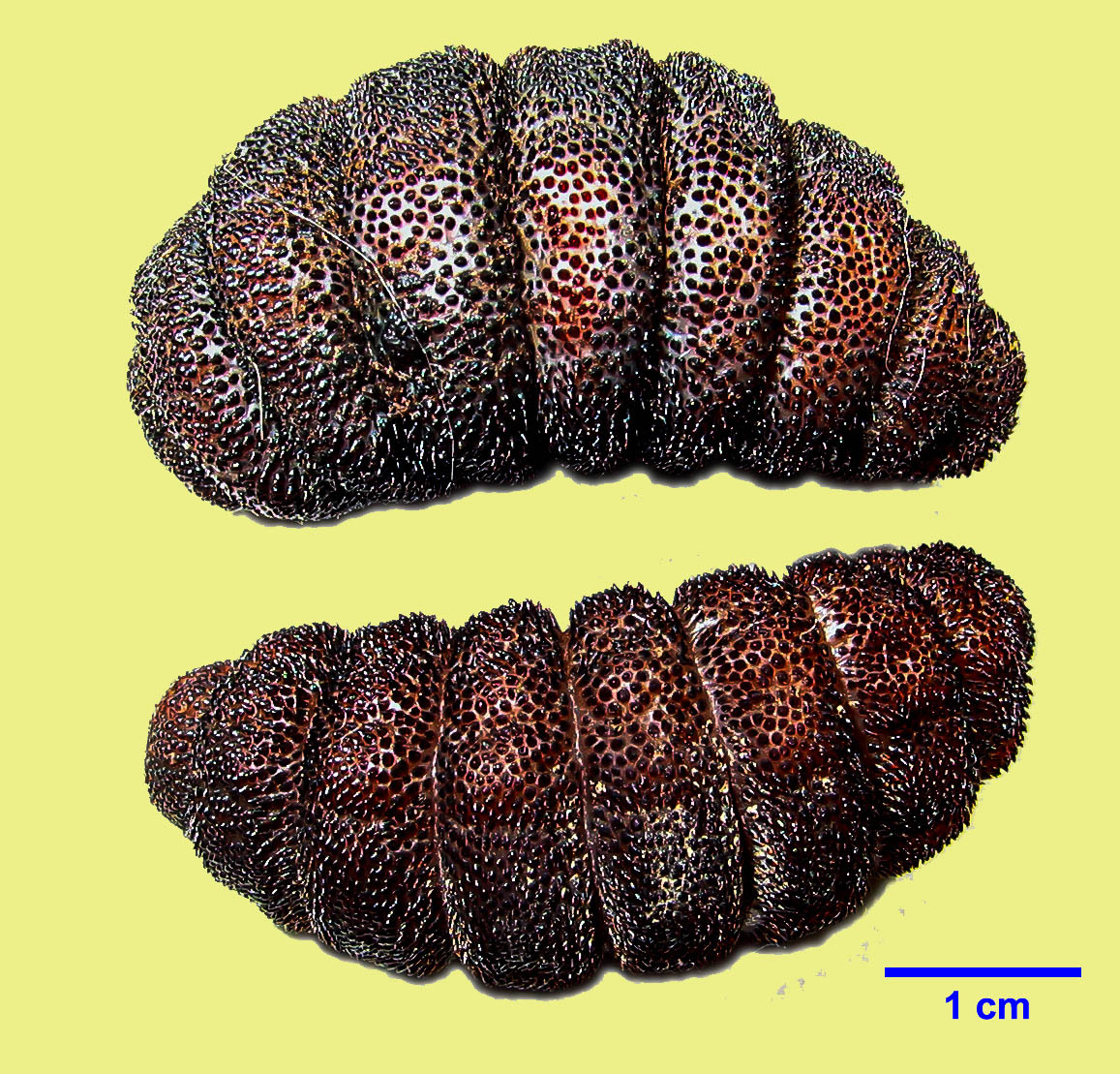

Morphology

Host range and geographic distribution

Life cycle - direct

Epidemiology

Infections are infrequently detected in dogs and cats in western Canada, generally with a history of being free-roaming around rabbit or rodent burrows.

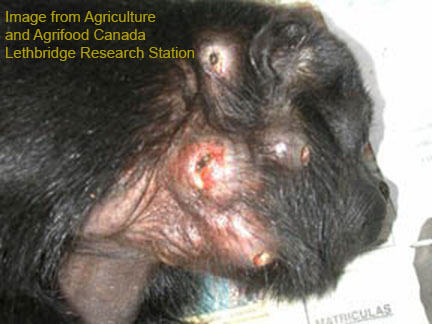

Pathology/clinical signs

Diagnosis

Third stage larvae are large and may be visualized via the breathing hole. There are no differential diagnosis for these bots in Canada, although there are other myiasis flies with much smaller larvae. Time of year (late summer/early fall) is helpful.

Treatment and control

For subcutaneous larvae, very careful surgical removal usually works well (crushing may trigger an anaphylactic response). It is important not to rupture the larva during removal, and to remember the possibility of secondary bacterial infection. Larvae in the mouth area and nose can often be removed relatively easily. Larvae in deeper tissues present a more serious problem.

Successful control of Cuterebra depends on preventing access by dogs and cats to areas where the female flies may have laid eggs. For rural pets this can be very difficult