Demodex canis

Demodex mites are common in the hair follicles and sometimes sebaceous glands of the skin of dogs around the world.

Summary

Demodectic mange in dogs is most common in young animals and has three main clinical presentations: 1) localized (1-4 isolated lesions) - often resolves spontaneously, excellent prognosis; 2) generalized (5 or more discrete sites) - does not resolve spontaneously, good prognosis in young animals with treatment, poor prognosis in older animals; and 3) pododemodecosis - affects the feet. Generalized demodectic mange in an older dog often signals underlying disease.Topical treatments like amitraz dips have largely been supplanted by newer isoxazolines and moxidectin/imidacloprid combination drugs. Pruritus is not a common feature of demodectic mange unless there is secondary bacterial infection, which is common with the generalized form of the disease. People have their own species of Demodex, and dogs are not considered a source of human infections.

Taxonomy

Subphylum: Chelicerata

Class: Arachnida

Subclass: Acari

Order: Prostigmata

Demodex species are in the same Order as Cheyletiella and Neotrombicula, which is different from that containing Sarcoptes, Notoedres, Psoroptes, Chorioptes and Otodectes, and from that containing Dermanyssus and Ornithonyssus. Demodex spp. are highly specific to their mammalian hosts and are considered part of the normal skin fauna.Three species of Demodex infest dogs: D. canis (the most common); D. injai; and D. cornei (short form, species status controversial).

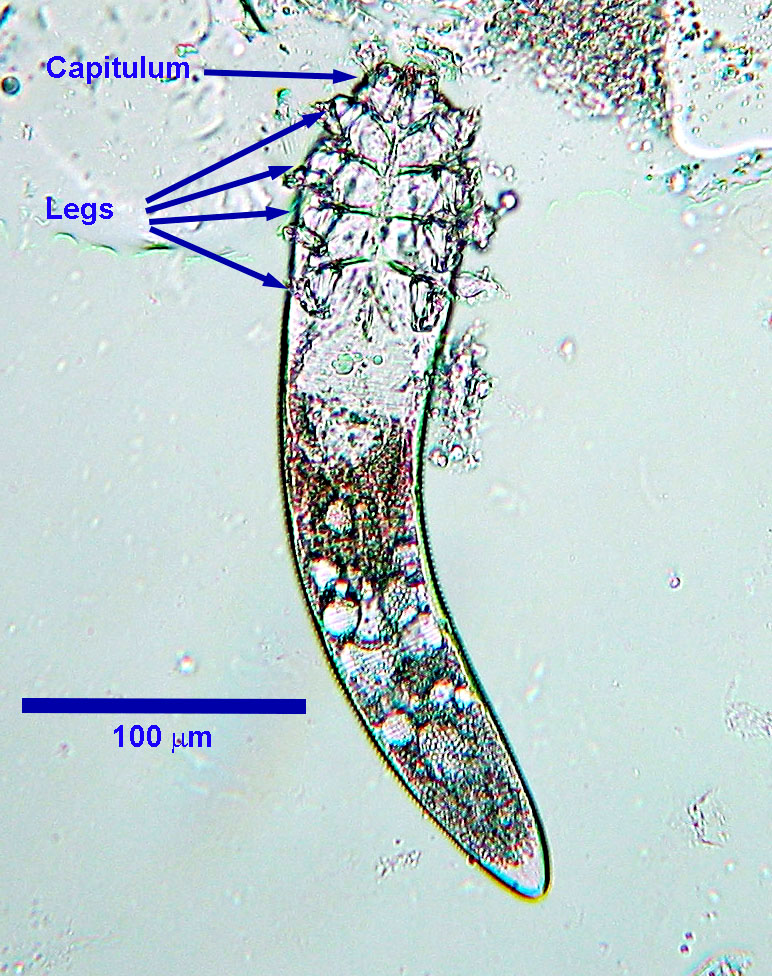

Morphology

Demodex injai is larger than D. canis, measuring up to approximately 375 µm in length, and D. cornei is smaller , measuring up to approximately 150 µm in length.

Host range and geographic distribution

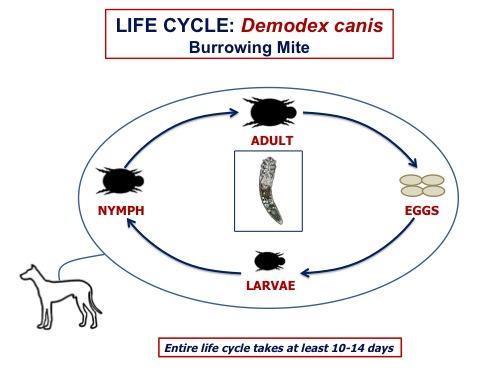

Life cycle - direct

Demodex mites complete their entire life cycle on the host. Adults live primarily in hair follicles, where the females lay eggs. Each egg hatches to release a larva, which moults through several larval and nymphal stages to become an adult. The entire life cycle requires at least three weeks.

Epidemiology

Pathology and clinical signs

Localized Demodecosis

Lesions are usually small, localized areas of hair loss, erythema and silvery scaling around the mouth, eyes and forelegs, with or without pruritus. These lesions often heal spontaneously. Rarely, and usually without other localized lesions, there are large numbers of mites in the ear canals, leading to a ceruminous otitis externa requiring treatment. Lesions may come and go over several months but, once resolved, recurrence is rare. Localized demodecosis does not often progress to the generalized disease. Most cases of localized demodecosis are in dogs < 1 year old and have an excellent prognosis, often resolving without any treatment.

Generalized Demodecosis

Generalized demodecosis is among the most severe and difficult to manage of all canine skin diseases. Lesions are usually widespread and more severe than with the localized form, and may involve whole regions of the body (by definition, more than 5 discrete sites on the body). Clinical signs associated with generalized demodecosis usually first appear in puppies 3 to 18 months old (juvenile onset). Juvenile onset generalized demodecosis has a good prognosis with modern treatments. Cases diagnosed in animals two to five years old, suggest the possibility of missed diagnoses of juvenile onset, or adult onset secondary to concomitant disease. Generalized demodecosis that is first diagnosed in dogs older than five years usually indicates underlying disease, for example neoplasia, causing immunosuppression that compromises the dog’s ability to control its Demodex population, and these generally have poor prognosis due to the underlying health issues.

Lesions of generalized demodecosis usually first appear on the face and limbs and coalesce to form large patches. The primary abnormality is follicular hyperkeratosis with follicular casts and folliculitis. Often there is also peripheral lymphadenopathy. With generalized demodecosis there is often secondary bacterial infection. If untreated, after several months the skin is covered with crusted, pyogenic, haemorrhagic, follicular-furuncular lesions, often primarily on the head and limbs and rarely on the abdomen. The owners of dogs thus affected often request euthanasia.

Lesions, which may be quite severe, are restricted to the feet, often again with bacterial complications. Pododemodecosis may or may not occur as a manifestation of generalized demodecosis, or may persist after the generalized disease has been successfully treated, in some cases becoming chronic and very difficult to manage. Pododemodecosis is not often seen.

Other, less common, clinical presentations have been associated with Demodex infestation in dogs: nodular skin disease (D. canis); greasy, truncal dermatitis (D. injai); and facial dermatitis (D. injai) (Information from Jackson HA and Marsella R, BSAVA Manual of Canine and Feline Dermatology, Third edition, 2012).

Diagnosis

Detection of Demodex sp. mites (which are normal skin fauna) is only meaningful when considered in the context of history and clinical signs. Mites can be detected in deep skin scrapings taken from a pinch a skin squeezed between the fingers to force the mites from the follicles (plus or minus KOH digestion). Especially in advanced cases, it may be necessary to examine scrapings from several areas to find the mites. The diagnosis is confirmed if large numbers of adult mites are found, or if there is a large ratio of larvae and nymphs to adults.

Recovery of a single mite from a scraping in a dog with clinical signs of demodecosis should be considered supportive of a diagnosis of demodecosis. Conversely, recovery of mites from clinically normal dogs (although rare), does not imply demodecosis, although such animals should be monitored for development of clinical signs

Sometimes skin biopsies can help establish a diagnosis of demodecosis if clinical signs are present but mites cannot be detected in deep skin scraping.

Treatment and control

Treatment of localized demodectic mange is usually unnecessary, unless it fails to self-resolve within a few months or progresses to the generalized form. Treatment of generalized and pododemodecosis are much more difficult. A combination of moxidectin and imidacloprid currently has a label claim for Demodex spp. Isoxazolines are now the drugs of choice for treating demodectic mange. Older topical treatments like Amitraz dips and lime sulfur baths are largely obsolete. Dogs less than one year old with generalized demodecosis, often with a familial history of the disease have good prognosis with treatment.

Adult onset generalized demodecosis is often less responsive to treatment unless the underlying cause can be addressed (such as discontinuing immunosuppressive treatment). Pups diagnosed with demodecosis (especially the generalized form), and their parents, should not be used for breeding.

Public health significance

References

Tater KC et al. (2008) Canine and feline demodecosis. Veterinary Medicine 103: 444-461

Neuber A et al. (2007) Treatment of canine demodecosis. UK Vet: Companion Animal 12: 54-57.

Note: some of the products mentioned in this paper may not be approved in Canada.

Gortel K (2006) Update on canine demodecosis. Veterinary Clinics of North America, Small Animal Practice 36 (1): 229-241.

Note: some of the products mentioned in this paper may not be available in Canada.

Mueller et al. (2020) Diagnosis and treatment of demodicosis in dogs and cats, Clinical consensus guidelines of the World Association for Veterinary Dermatology. Veterinary Dermatology 31:4-e2. https://wavd.org/wp-content/uploads/diagnosis-and-treatment-of-demodicosis-in-dogs-and-cats-mueller-et-al-2020-veterinary-dermatology.pdf