Dermacentor andersoni: the Rocky Mountain wood tick

Dermacentor andersoni is a large reddish-brown to gray-brown tick. In Canada, it is found from central Saskatchewan and west through Alberta and into British Columbia.

Summary

Taxonomy

Subphylum: Chelicerata

Class: Arachnida

Subclass: Acaria

Order: Ixodida (= Metastigmata)

Family: Ixodidae

As arachnids, ticks are closely related to mites and spiders. Hard ticks of veterinary importance in Canada include Rhipicephalus sanguineus, Dermacentor variabilis, D. albipictus, and various Ixodes spp. including I. scapularis and I. pacificus, the vectors of Borrelia burgdorferi - the cause of Lyme disease.

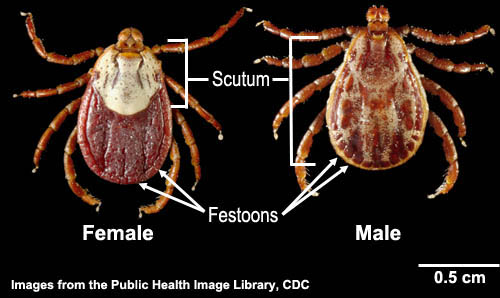

Morphology

Host range and geographic distribution

Life cycle

Adult ticks overwinter in the environment and begin to emerge from hibernation (exit diapause) in early spring shortly after snowmelt (a period of days above 5°C). They will actively search (quest) for hosts by climbing to the tips of grass blades and other low vegetation waiting for appropriate hosts to brush past. Numerous mammals have been reported as hosts for adult D. andersoni. They are generally larger species including deer, elk, coyotes, dogs, horses, cattle and people. As the weather warms the ticks become active in greater numbers, reaching a peak in the late spring (temperatures between 16°C and 19°C and above 20% humidity) or possibly early summer (in Saskatchewan). As days get hotter and drier (a period of days above 20°C and below 20% humidity) the number of active ticks declines rapidly. Most adult ticks that have not found hosts by this time seek protection under ground debris and generally will not become active again until the following spring. These unfed ticks can survive for at least two years and possibly longer and will become active each spring. Questing adult D. andersoni have been reported from February to November in regions of their North American geographic range but peak activity seems to be in May and June.

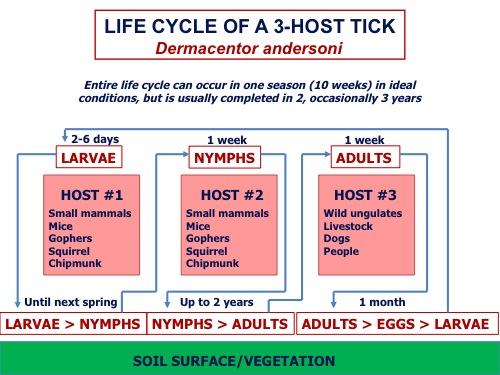

Adult ticks that have been successful in finding a host will feed for about a week, mate during that time, and drop off the host into the environment. Females lay eggs about seven days later and then die. Eggs hatch approximately a month after being produced with the emerged larvae dispersing from the egg mass and actively seeking hosts, generally small mammals including mice, squirrels, gophers, chipmunks and small carnivores. If successful in finding a host they will feed for 2-6 days and fall off into the environment where they moult and become nymphs. It is possible to find questing larval D. andersoni in regions of their North American geographic range from March to October, with peak numbers found in June and July. Larval ticks can survive, unfed, for at least a year and will overwinter.

Most nymphs do not feed during the summer in which they have developed and will be inactive, under ground cover, until the following spring or early summer. When they do begin questing they will search for small mammal hosts and, if successful, feed for about a week. They then fall off the host and moult to the adult stage. Active D. andersoni nymphs can be found in regions of their North American geographic range from March to October with peak numbers seen in May through June. They may be able to survive a second winter beneath ground debris. Newly emerged adults generally do not feed until a number of weeks after moulting and therefore generally do not feed until the following spring.

The entire life cycle of D. andersoni can occur in one season (68 days under ideal laboratory conditions) but it is generally completed in two and occasionally three years. Factors that influence life cycle completion include temperature, humidity and host availability. Conditions supportive of tick development can advance the timing of the cycle and increase tick abundance. With continued climate change, earlier, warmer springs may lead to adult ticks questing earlier in the year, but this may be countered by hotter summers and regional variation in precipitation.

Epidemiology

Dermacentor andersoni is seasonal in its activity with adults (the life stage primarily seen on domestic animals) actively questing for hosts in spring and early summer. Climatic factors such as temperature, wind and moisture levels will affect tick activity.

Dermacentor spp. ticks are most active on sunny, windless days in warm spring or moderate summer temperatures. They tend to be found on tall grass or low brush, along the edges of trails, pastures, and wooded areas with deeper litter for environmental stages. While ticks tend to be associated with rural and wilderness regions, they are increasingly found in urban green spaces (river valleys, parks, off leash areas, etc).

Pathology and clinical signs

Dermacentor andersoni transmits the causal agents of Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (RMSF) (Rickettsia rickettsii) and tularaemia (Francisella tularensis), as well as the Colorado Tick Fever (CTF) virus (which seems not to occur naturally in animals). Dermacentor andersoni might also be a significant vector for Anaplasma (e.g. A. marginale) in ungulates. These pathogens are rare in dogs in Canada, RMSF is an issue in dogs in the United States.

Diagnosis

Treatment and Control

Depending on the owner’s risk tolerance, there are 3 tiers to tick control on pets; the first is simply avoiding tick habitat, especially in spring and early summer. The second is to do thorough tick checks and remove ticks from pets within 6-24 hours of being active in tick habitat. This timing is based on the minimum amount of time for ticks to attach, feed, and transmit pathogens. Ticks can be carefully removed with tweezers (or fingers) by grasping the mouth parts as close to the skin as possible (ticks secrete a glue patch and embed their mouthparts deep into the skin, so use slow and steady pressure). Bites should be washed and monitored for signs of local bacterial infection

The third tier involves administration of topical or oral tick preventatives, which serve as repellents or systemic products that rapidly kill ticks within hours of infestation. Systemic isoxazolines are rapidly becoming the treatment of choice for tick prevention in dogs and cats, while older repellent type products (i.e. imidacloprid with permethrin, and some pyrethrin/pyrethroid-based products) may still be used in dogs, but are unsafe for cats