Diphyllobothrium species

Adult cestodes of the genus Diphyllobothrium live in the small intestine of dogs and other fish-eating mammals and birds in many parts of the world, especially the northern hemisphere.

Summary

Adult cestodes of the genus Diphyllobothrium (now Dibothriocephalus) live in the small intestine of dogs and other fish-eating mammals and birds in many parts of the world, especially the northern hemisphere. In Canada, most human and canine infections are associated with freshwater species, D. latum (now Dibothriocephalus latus) and D. dendriticum, although there are also marine species (D. ursi and D. nihonkaiense) associated with bears and Pacific salmon. The parasites have an indirect life cycle involving a copepod first intermediate, a fish second intermediate host, and often a fish paratenic host. The life cycle stage infective for definitive hosts is the plerocercoid, which are usually visible in the flesh and sometimes other tissues of the fish. Diphyllobothrium (now Dibothriocephalus) in dogs is rarely associated with clinical signs other than mild gastro-intestinal upsets. In Canada, these tapeworms are rare in urban pet dogs, but relatively common in dogs with access to uncooked, unfrozen fish in rural and remote regions . Clearing infections requires high doses of praziquantel, repeated several times, and is off-label. Human infection also occurs in Canada as a result of eating infected fish (not through contact with dogs or dog feces), and can be associated with mild gastro-intestinal signs.

Taxonomy

Phylum: Platyhelminthes

Class: Cestoda

Order: Pseudophyllida

Family: Diphyllobothriidae

Diphyllobothrium (now Dibothriocephalus) and Spirometra are two genera within the Order Pseudophyllidea that are important in domestic animals and/or people.Other pseudophyllids such as Ligula, Schistocephalus, and Bothriocephalus may be found in fish and fish-eating vertebrates and are not considered of veterinary importance.

Pseudophyllid tapeworms are very different from those within the Order Cyclophyllidea (including Taenia and Dipylidium), particularly with regard to life cycles and ecology. Most tapeworms significant for domestic animals and birds and wildlife in Canada are members of the Order Cyclophyllidea.

Note: Our understanding of the taxonomy of parasites is constantly evolving. The taxonomy described in wcvmlearnaboutparasites is based on Deplazes et al. eds. Parasitology in Veterinary Medicine, Wageningen Academic Publishers, 2016.

Morphology

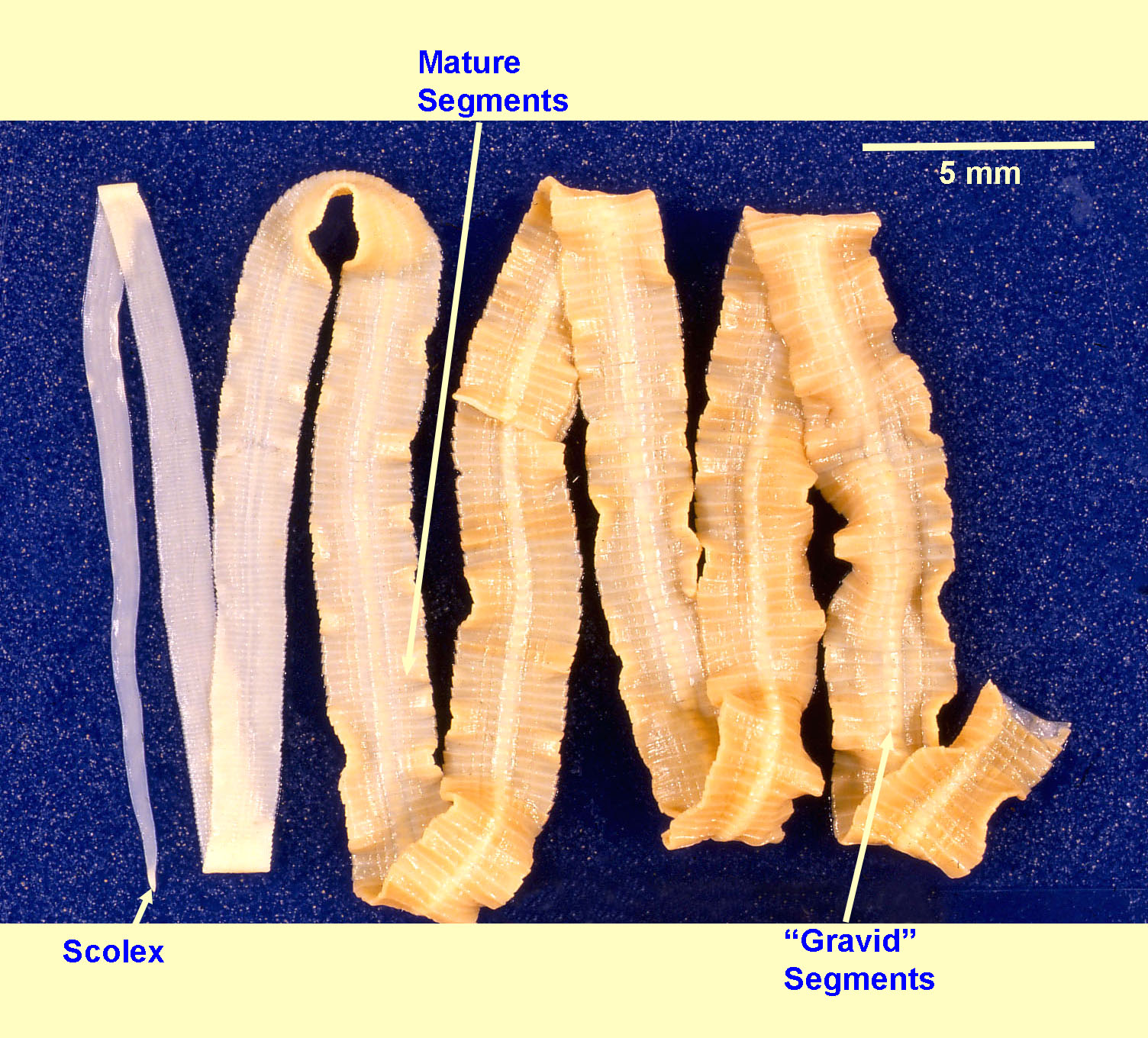

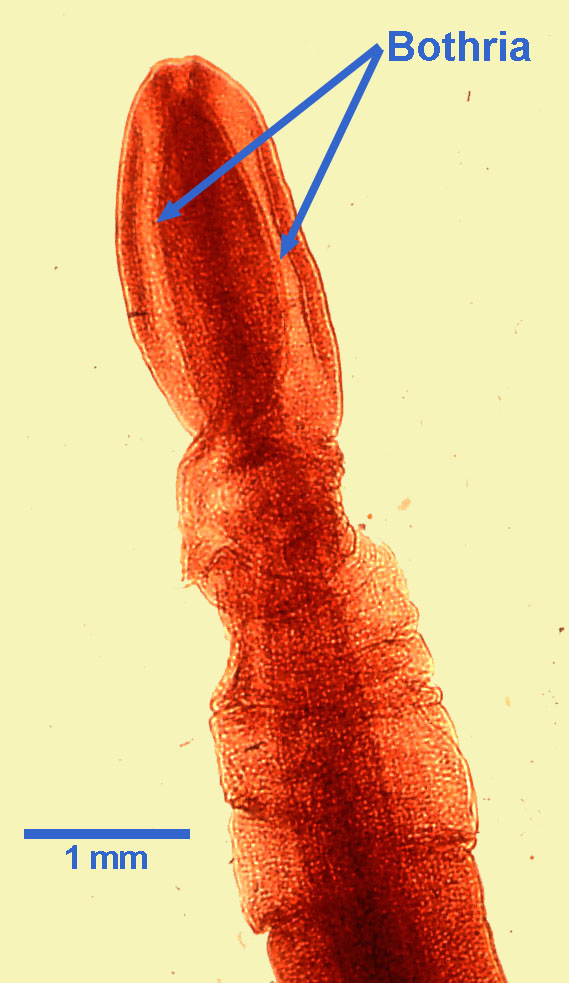

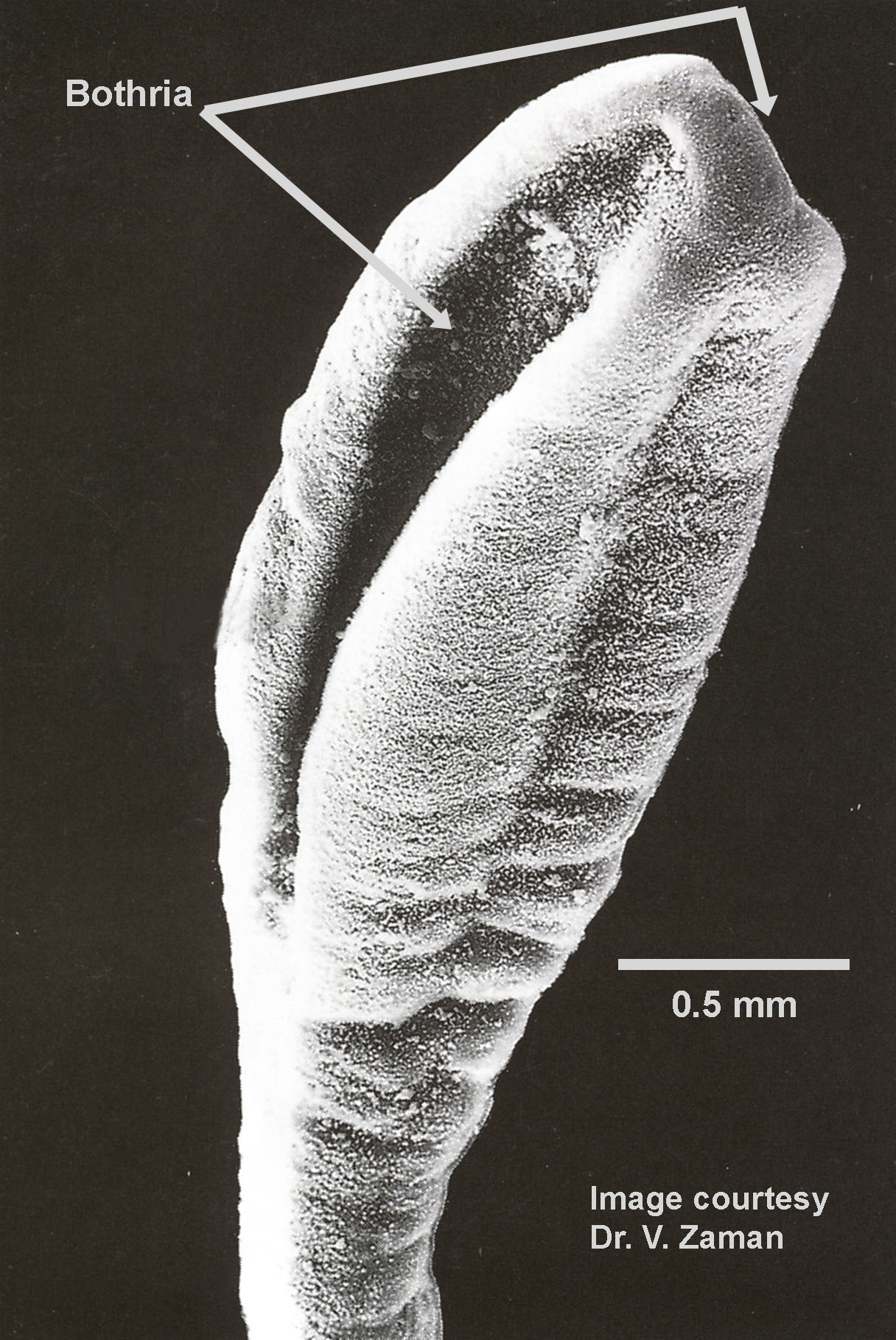

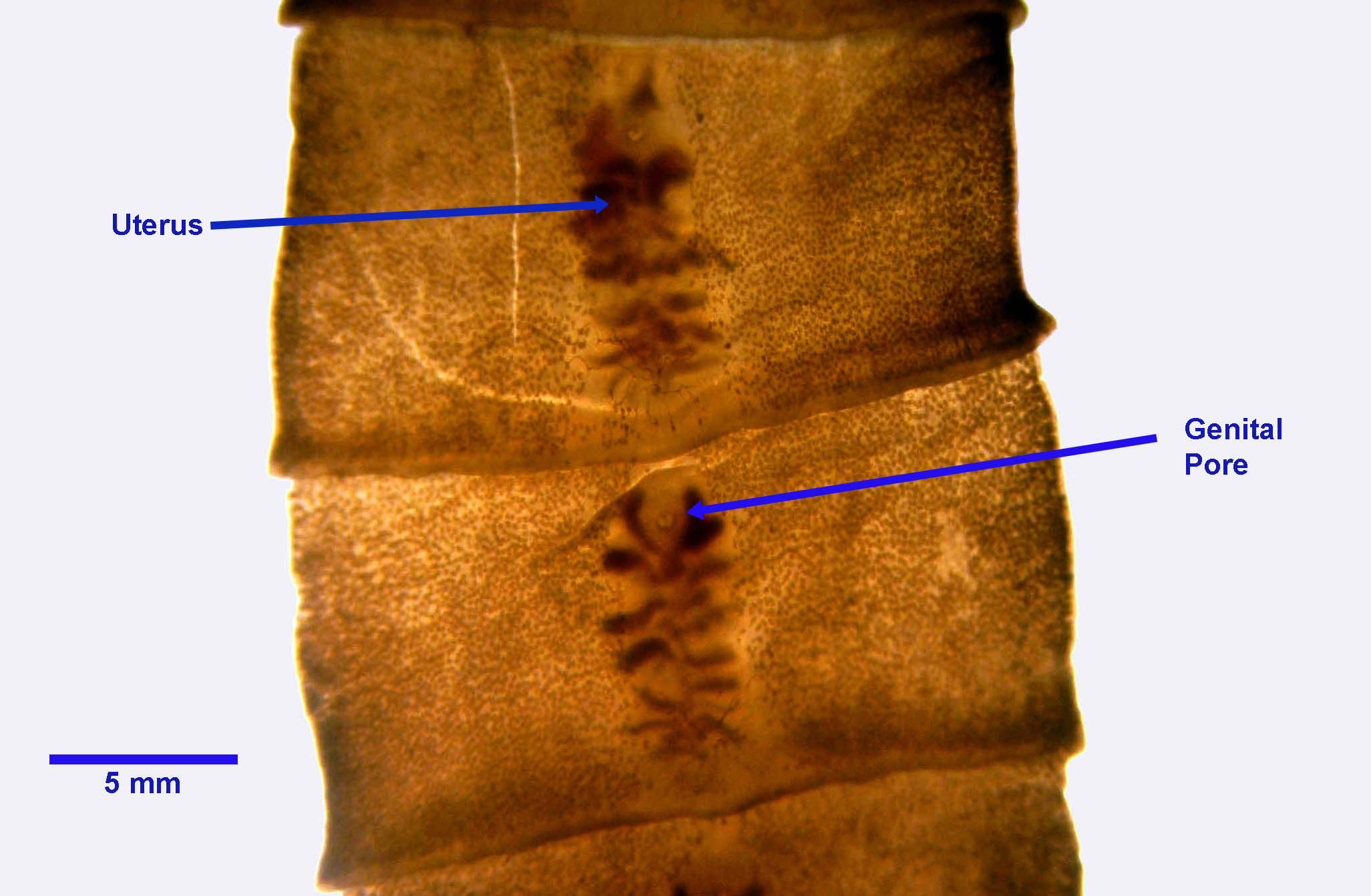

Adult Diphyllobothrium (now Dibothriocephalus) species are large (1-15 m in length) and have an anterior scolex (attachment or holdfast organ), behind which is the ribbon-shaped, segmented body. Typically, the newly-formed immature segments in the anterior part of the tapeworm are smaller than the mature and gravid segments towards the posterior. The scolex does not have a rostellum or hooks or circular suckers, but has two lateral bothria (longitudinal muscular grooves) immediately behind the tip. Each mature segment of Diphyllobothrium contains a single set of reproductive organs with a ventral genital pore and a ventral uterine pore, both slightly anterior to the uterus. The central uterus gives the adult cestode a zipper-like appearance distinct from Taenia spp. adult cestodes.

In the gravid segments, the eggs of Diphyllobothrium (now Dibothriocephalus) are contained in the central, coiled uterus. Details of the egg structure are not visible in the segments, and the uterus and the genital pore are the only structures visible even in specimens that are fixed and stained. The structure of the scolex and the presence of ventral vs lateral genital pore are the primary means of distinguishing adult pseudophyliid from cyclophyllid cestodess.

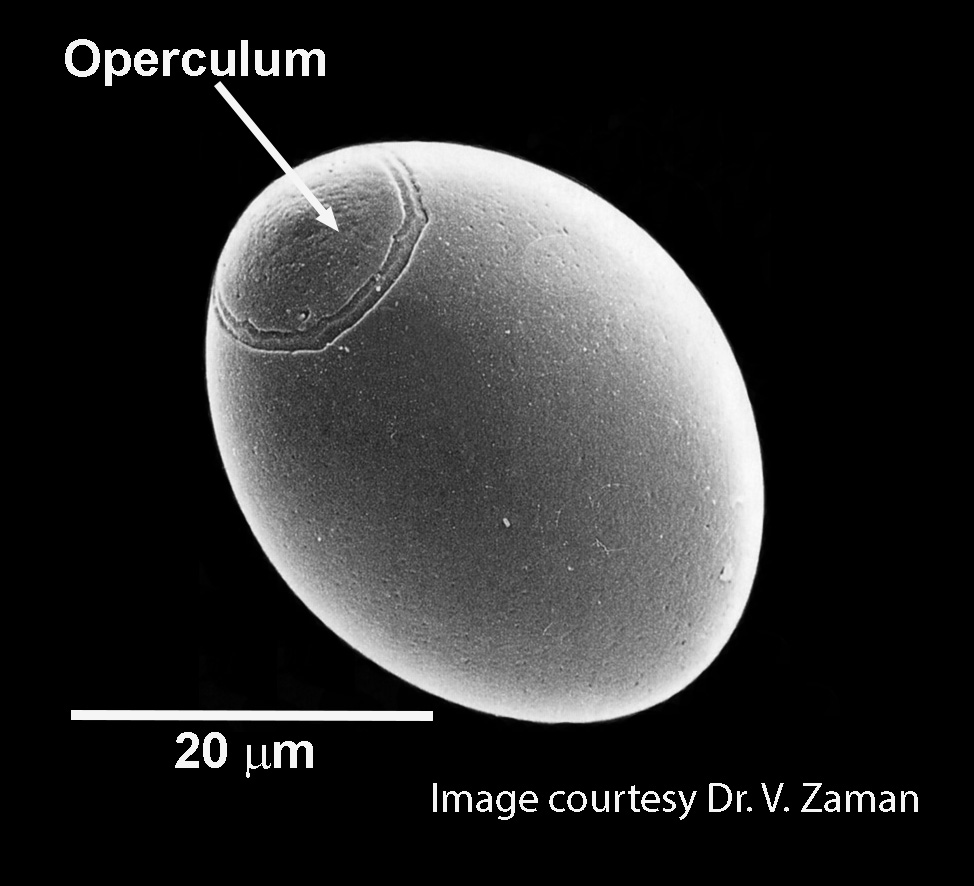

The eggs of Diphyllobothrium (now Dibothriocephalus) measure approximately 65 to 70 µm by 40 to 50 µm, are oval, with a thin smooth shell and an operculum (lid) at one end. At the opposite end, there is often a small protuberance. Details of the internal structures of the eggs are not usually visible in specimens recovered from fecal flotations.

Host range and geographic distribution

Life cycle

Adult Diphyllobothrium (now Dibothriocephalus) live in the small intestine of the definitive hosts and, like all cestodes of veterinary importance, are hermaphrodites. The presence of a uterine pore in the gravid segments means that eggs can be shed from the adult parasites without the loss of gravid segments, although these too may be passed in the feces of the definitive host, often as long ribbons.

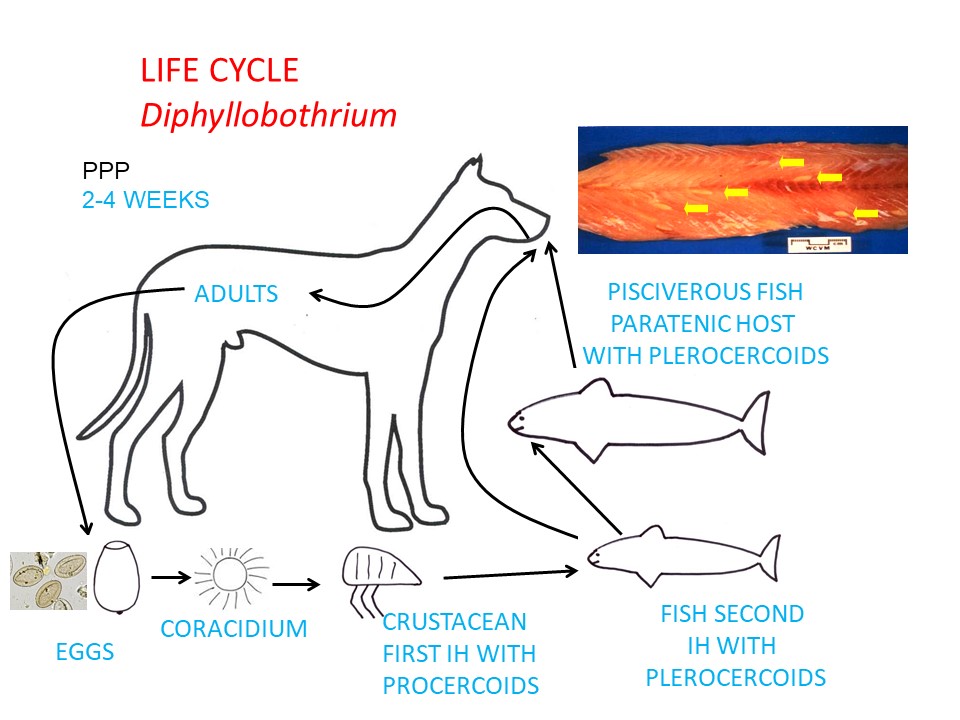

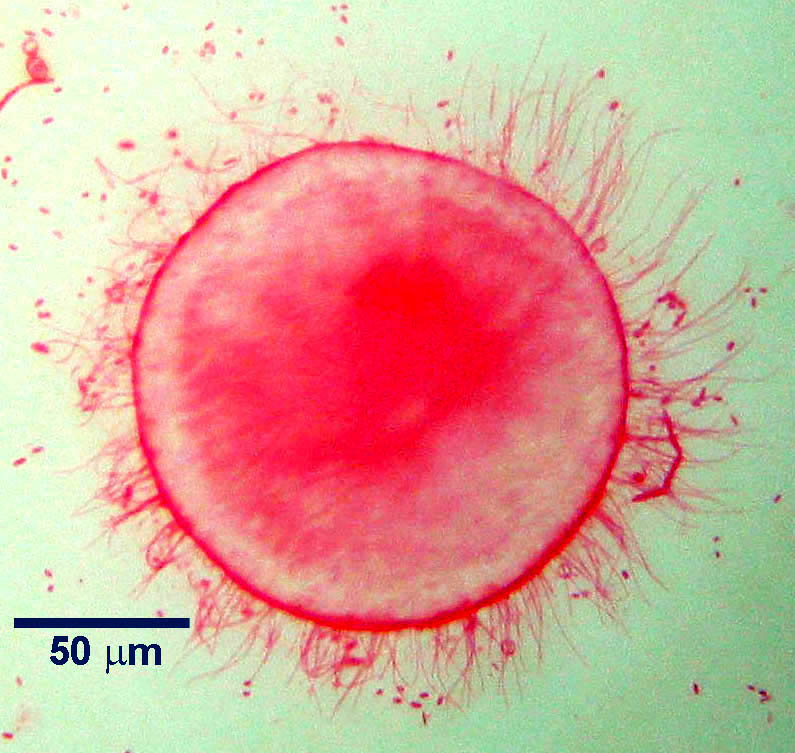

After a few days of development in an aquatic environment, a ciliated, motile coracidium(first larval stage) develops within each egg and, following loss of the operculum, is released into the surrounding water. For the life cycle to continue, the coracidium must be ingested by a small copepod ( crustacean) first intermediate host, in which a procercoid (second larval stage) develops.

Coracidium Copepod IH (not to scale)

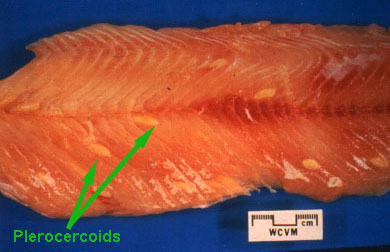

If the copepod is ingested by a suitable fish second intermediate host, then the procercoid released from the copepod migrates into various tissues in the fish and develops to the plerocercoid (third larval stage). The site(s) of development of the plerocercoid vary with the species: for D. latum the flesh, and for D. dendriticum and D. ursi the viscera. The plerocercoid is the life cycle stage infective for the definitive hosts. If an infected fish is eaten by a suitable piscivorous fish, the plerocercoids can migrate into the tissues of the second fish, which thus serves as a paratenic host.

Plerocercoid from fish IH

Following ingestion by a definitive host of an infected fish, the plerocercoids are released, attach to the intestinal mucosa and develop to an adult tapeworm. The prepatent period is 2- 4 weeks in dogs.

Epidemiology

Diphyllobothrium (now Dibothriocephalus) depends on an aquatic environment for maintenance and spread. Water is required for the eggs, the coracidium, and for all its intermediate and paratenic hosts. Factors affecting the development and survival of the eggs, the coracidia, the copepods and the fish will all influence parasite transmission, as will the role of fish in the diet of the definitive hosts. People and dogs in western Canada are most commonly infected by consumption of uncooked, unfrozen predatory freshwater fish.

Pathology and clinical signs

Generally, adult Diphyllobothrium (now Dibothriocephalus) cause no obvious problems in animals, although shedding of adult cestodes is aesthetically concerning to most dog owners.

Diagnosis

Treatment and control

There are no products approved in Canada for Diphyllobothrium (now Dibothriocephalus) spp. in dogs, but oral praziquantel is the product of choice. It is an extralabel use at a higher than normal dose (7.5 mg/kg once a day for two days). Multiple treatments may be necessary, and dose may need to be increased to 10 mg/kg (or more) to clear infections.

Effective control of Diphyllobothrium (now Dibothriocephalus) in dogs requires prevention from consuming plerocercoids in unfrozen, uncooked fish. For logistical and cultural reasons, this is often difficult to achieve. Cooking the fish thoroughly, or freezing it for several days at minus 10C or lower, will kill the plerocercoids. Preventing dogs from defecating in or near freshwater will also help break the life cycle.

Public health significance

People acquire Diphyllobothrium (now Dibothriocephalus) the same way dogs do, by consuming plerocercoids in unfrozen, uncooked fish., especially the flesh for D. latum, and the viscera for D. dentriticum and D. ursi.D. latum, the primary species in areas of Europe and elsewhere, was historically a cause of pernicious anaemia (Vitamin B12 deficiency) in children, but this appears to have a multifactorial etiology. This type of anaemia has not been reported in Canada, but the parasite may cause non-specific and usually mild GI symptoms. Adult cestodes can live for years, if not decades, and passage of adult cestodes may cause considerable distress. D. nihonkaiense is a relatively newly described species in North America, first detected in a resident of France who had consumed raw Pacific salmon imported from Canada.

References

Conboy G (2009) Cestodes of dogs and cats in North America. Veterinary Clinics of North America Small Animal Practice 39: 1075-1090.

Jenkins E et al (2013). Tradition and transition: Parasitic zoonoses of people and animals in Alaska, northern Canada, and Greenland. Advances in Parasitology 82: 33-204. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-407706-5.00002-2

https://research-groups.usask.ca/cpep/parasites/cestodes-supplementary.php