Dipylidium caninum

Dipylidium caninum is a tapeworm of the small intestines of domestic dogs and cats and free-ranging canids and felids.

Summary

Taxonomy

Class: Cestoda

Order: Cyclophyllida

Family: Dipylidiidae

Members of the Family Dilepididae include Dipylidium, Joyeuxiella, and Diplopylidium spp.

All cyclophyllid tapeworms have basically similar structures and life cycles, although the details differ. Similarities among the genera within a cyclophyllid family are greater than those between families. They have similar structures and life cycles to other cyclophyllid cestodes.

We have recently recognized that dogs and cats have their own host-specific “strains” of Dipylidium caninum, although cross infection can occur.

Morphology

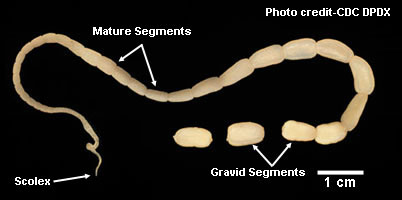

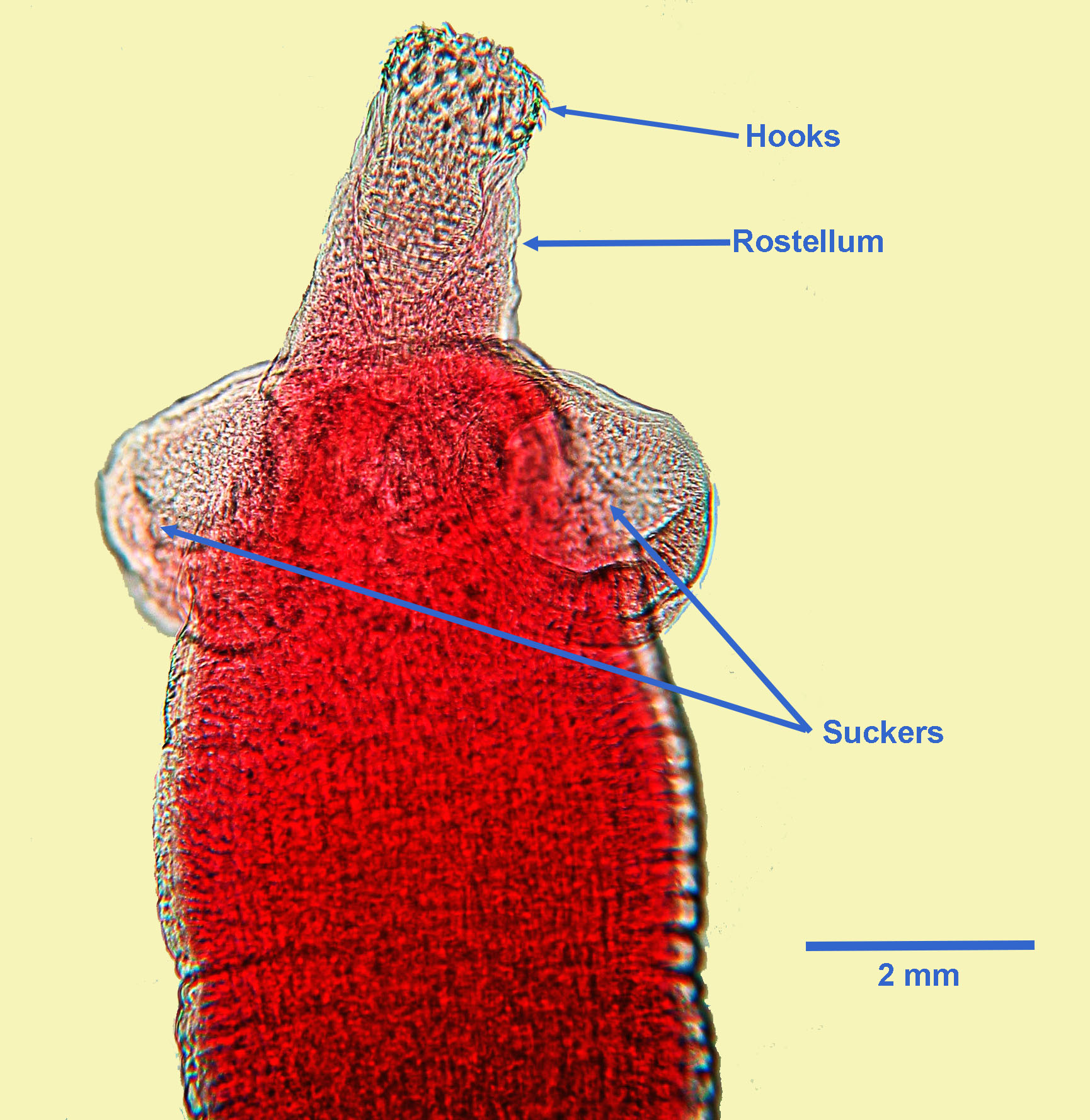

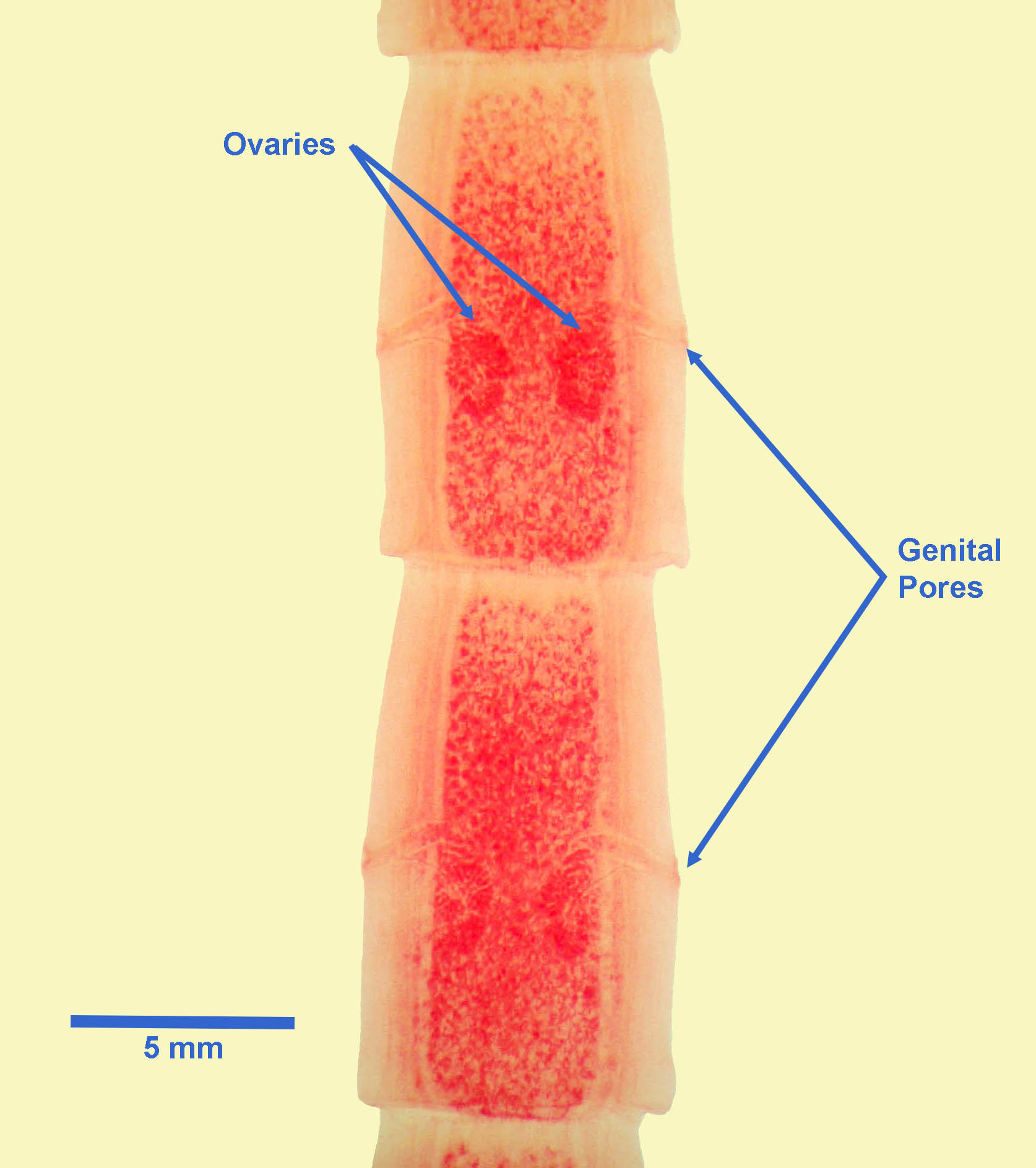

Adult D. caninum are large (up to 50 cm in length, or more) and have an anterior scolex (attachment or holdfast organ), behind which is the ribbon-shaped, segmented body of the tapeworm. Typically, anterior immature segments are smaller than mature and gravid segments towards the posterior. At the anterior tip of the scolex is a rostellum, which is armed with several circles of hooks. Behind the rostellum are four circular, muscular suckers. Each mature segment of D. caninum contains two sets of reproductive organs, each with a lateral genital pore at about the mid-point of each lateral margin of the segment.

Scolex

Mature segments Gravid segments

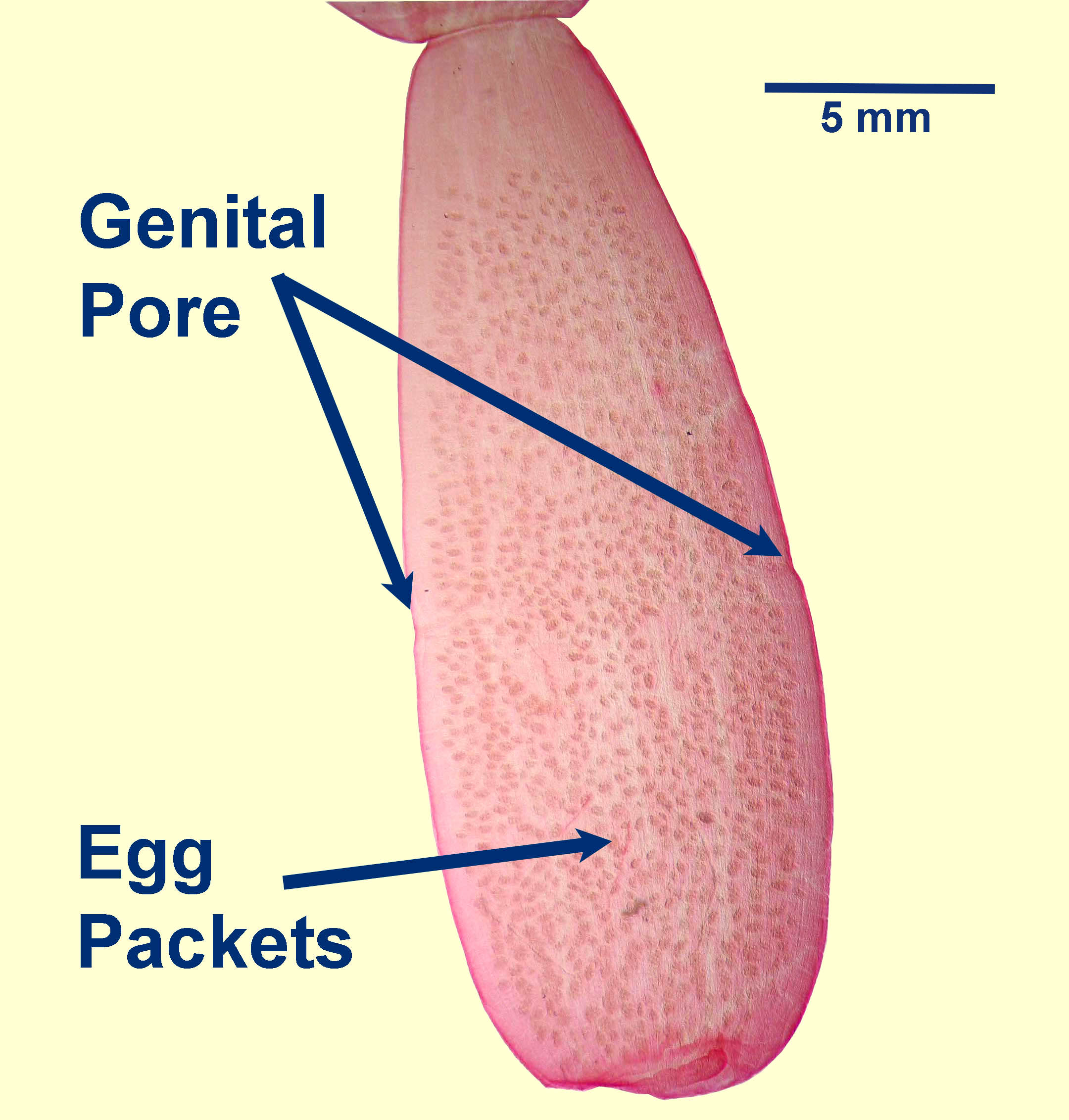

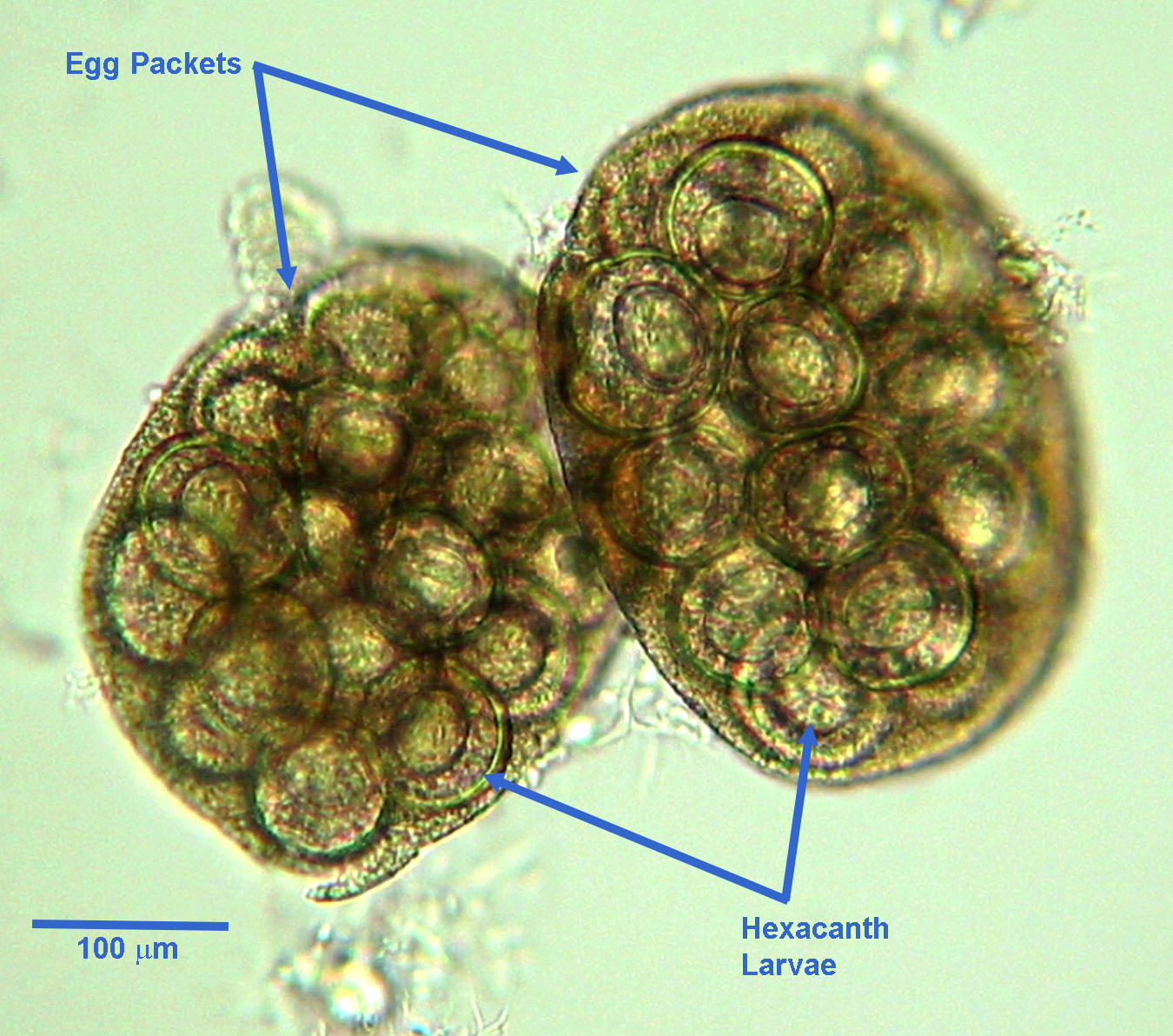

In gravid segments, the eggs of D. caninum are grouped in very distinctive egg packets (egg capsules) throughout the central area of the segment. Each egg packet measures up to 200 µm in diameter and contains up to approximately 30 eggs, each of which is approximately 25 to 50 µm in diameter. In most specimens submitted to a diagnostic laboratory, the genital pores and the egg packets are the only structures visible, even in fixed, stained specimens. Each egg has a fragile shell and contains a typical hexacanth larva with six hooks. Details of the egg packets are not always easily visible in the segments.

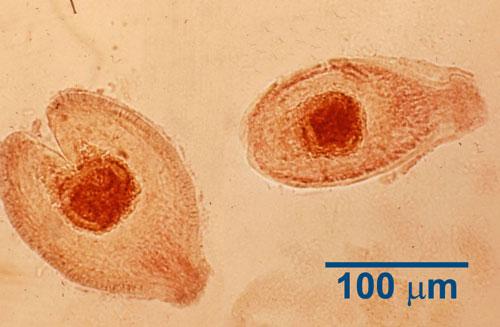

Eggs inside of egg packets Flea IH

Cysticercoids from flea IH

Host range and geographic distribution

Life cycle - indirect

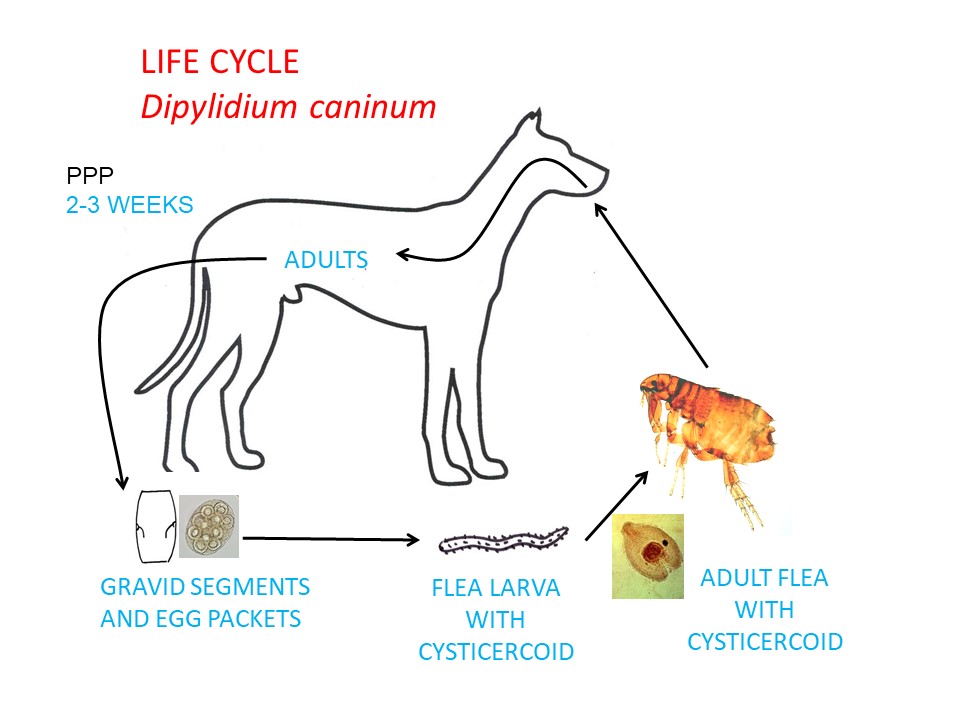

Adult D. caninum live in the small intestine of the definitive hosts and, like all cestodes of veterinary importance, are hermaphrodites. Gravid segments, which are full of egg packets, drop off and pass intact in the feces or, rarely, disintegrate in the GI lumen, releasing the egg packets, which are also passed in the feces.

Egg packets, or eggs, are ingested by a suitable flea larva (or possibly a chewing louse) although the epidemiological significance of lice is not known. In the arthropod intermediate host (required for completion of the life cycle), the eggs hatch in the GI system. The hexacanth larva released from each egg then penetrates the GI wall and migrates to the body cavity, where it develops into a cysticercoid, which is the metacestode stage for cyclophyllid tapeworms that utilize invertebrate intermediate hosts. The cysticercoid remains in the flea as it develops through its larval stages to the pupa and ultimately to an adult flea. Each cysticercoid contains only a single protoscolex and each protoscolex has the potential to become the scolex of an adult tapeworm.

The life cycle continues when the cysticercoid in the infected flea is eaten by a dog or a cat or other suitable definitive host. Here the infective stage is released from the intermediate host tissues, attaches to the mucosa of the small intestine using the scolex, produces segments and completes its development to an adult. Eggs are produced within 2-3 weeks of infection of the dog or cat; this short pre-patent period has implications for epidemiology and control.

Epidemiology

Pathology and clinical signs

Diagnosis

Treatment and control

Public health significance

References

Beugnet et al., (2018 )Analysis of Dipylidium caninum tapeworms from dogs and cats, or their respective fleas Part 2. Distinct canine and feline host association with two different Dipylidium caninum genotypes. Parasite 25:31 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6013090/

Conboy G (2009) Cestodes of dogs and cats in North America. Veterinary Clinics of North America Small Animal Practice 39: 1075-1090.

Challadurai et al. (2018) Praziquantel resistance in the zoonotic cestode Dipylidium caninum. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 99: 1201-1205.

https://www.ajtmh.org/view/journals/tpmd/99/5/article-p1201.xml

https://research-groups.usask.ca/cpep/parasites/cestodes-supplementary.php