Dirofilaria immitis

The nematode Dirofilaria immitis (heartworm) occurs in domestic dogs and less often in cats, and in free-ranging canids and other carnivores, in many regions of the world.

Summary

Currently, diagnostic testing for heartworm infection in dogs is usually based on the detection in serum of antigen produced by mature female parasites and is recommended only in dogs that live in or travel to endemic regions, at least 6 months after the last possible transmission, and before commencing monthly prophylaxis. In endemic regions in Canada macrocyclic lactones are given monthly to dogs from June to November to prevent the establishment third-stage larvae acquired from mosquitoes in the previous month. In the US, D. immitis has developed resistance to the macrocyclic lactones, emphasizing the need to test dogs on prophylaxis to detect resistance, and that dogs should not be imported from regions where resistant heartworm is established. Infection with adult D. immitis is extremely rare in Canada, and treatment with an adulticide (melarsomine), a microfilaricide (a macrocyclic lactone) and doxycycline (an antibiotic to kill Wolbachia, the bacterial endosymbiont of filarial nematodes) is recommended, with exercise restriction to reduce risk of pulmonary embolism. People can, rarely, acquire subcutaneous or lung nodules associated with D. immitis from infected mosquitoes, but only one foreign-acquired case has been reported in Canada.

In cats antigen detection tests are not suitable for (mature parasites are rare in this host), a test that detects antibodies to D. immitis has been developed, but it has poor sensitivity. Heartworm infection can be prevented in cats as in dogs, but there is no indication that this is necessary in Canada at the current low prevalence

Taxonomy

Phylum: Nematoda

Class: Secernent

Order: Spirurida

Superfamily: Filaroidea

Family: Onchorcercidae

Spirurids of veterinary importance include stomach dwelling nematodes (i.e. Physaloptera, Spirocerca, Habronema, and Draschia) as well as members of the Superfamily Filarioidea (i.e. Stephanofilaria, Dirofilaria, Onchocerca, and Setaria). All undergo indirect life cycles using arthropod intermediate hosts. Among the close relatives of D. immitis are species within the genus Onchocerca, including O. cervicalis of horses, and O. volvulus, the cause of “River Blindness” in people in many tropical countries, as well as Wuchereria and Brugia species, which are associated with human filariasis. Like other filarial nematodes, the rickettsial organism Wolbachia is an important symbiont in Dirofilaria immitis, and this has significance for treatment of heartworm disease.

Morphology

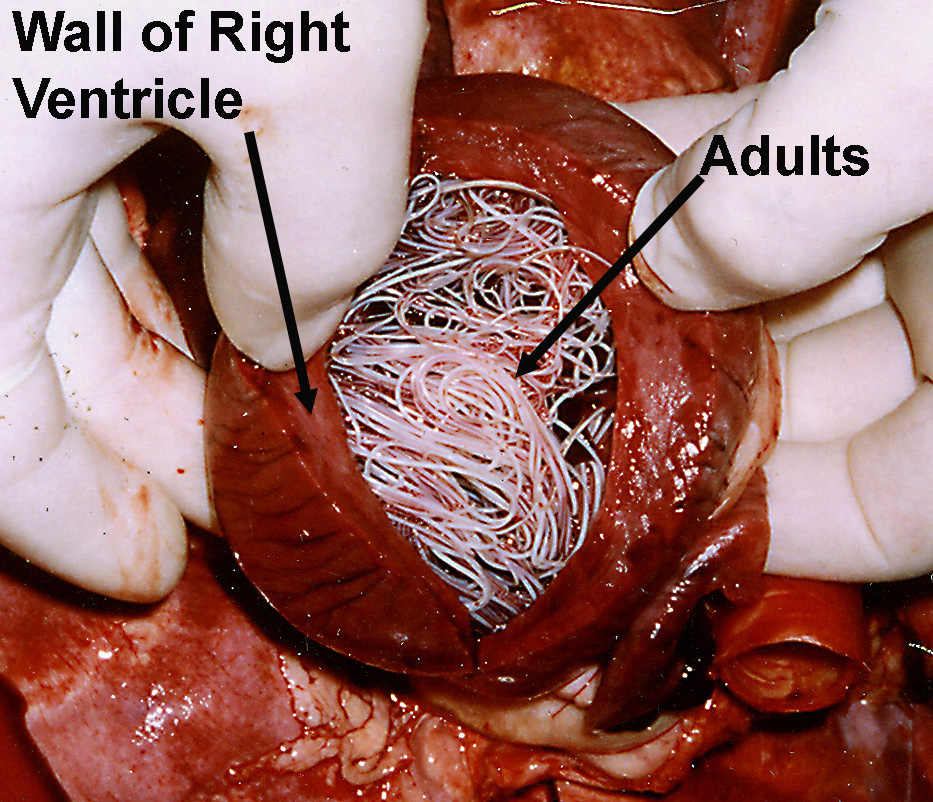

Adult D. immitis are up to approximately 15 cm (males) and 30 cm (females) in length and are clearly visible to the naked eye. Macroscopically, neither males not females have any notable morphological features. The identification of adult parasites is usually based primarily on their location within the host.

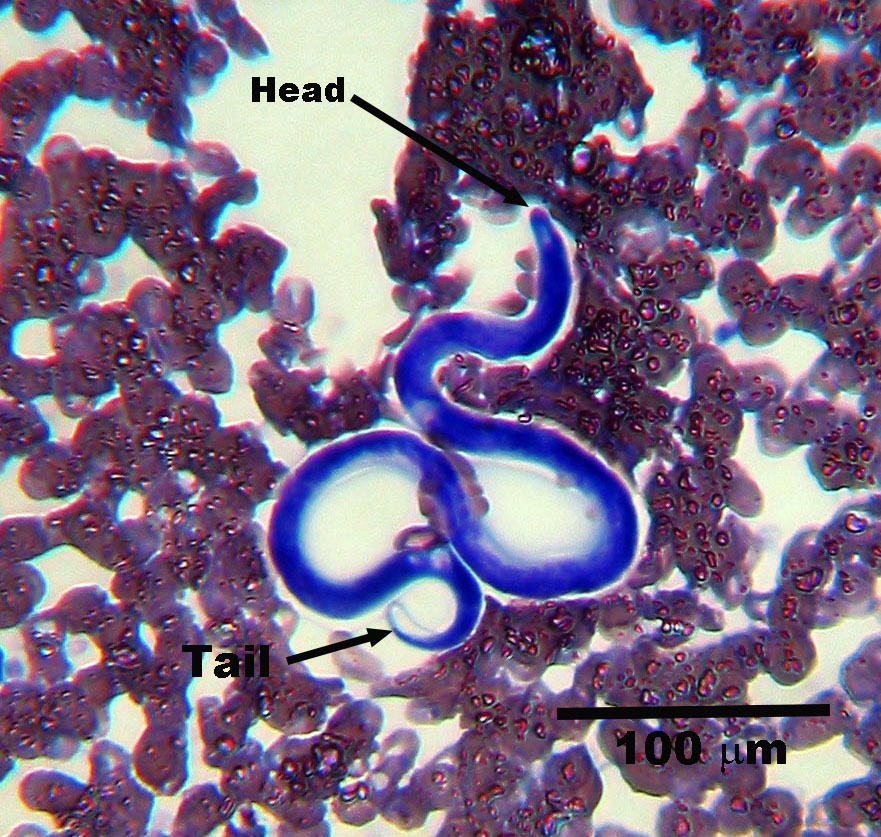

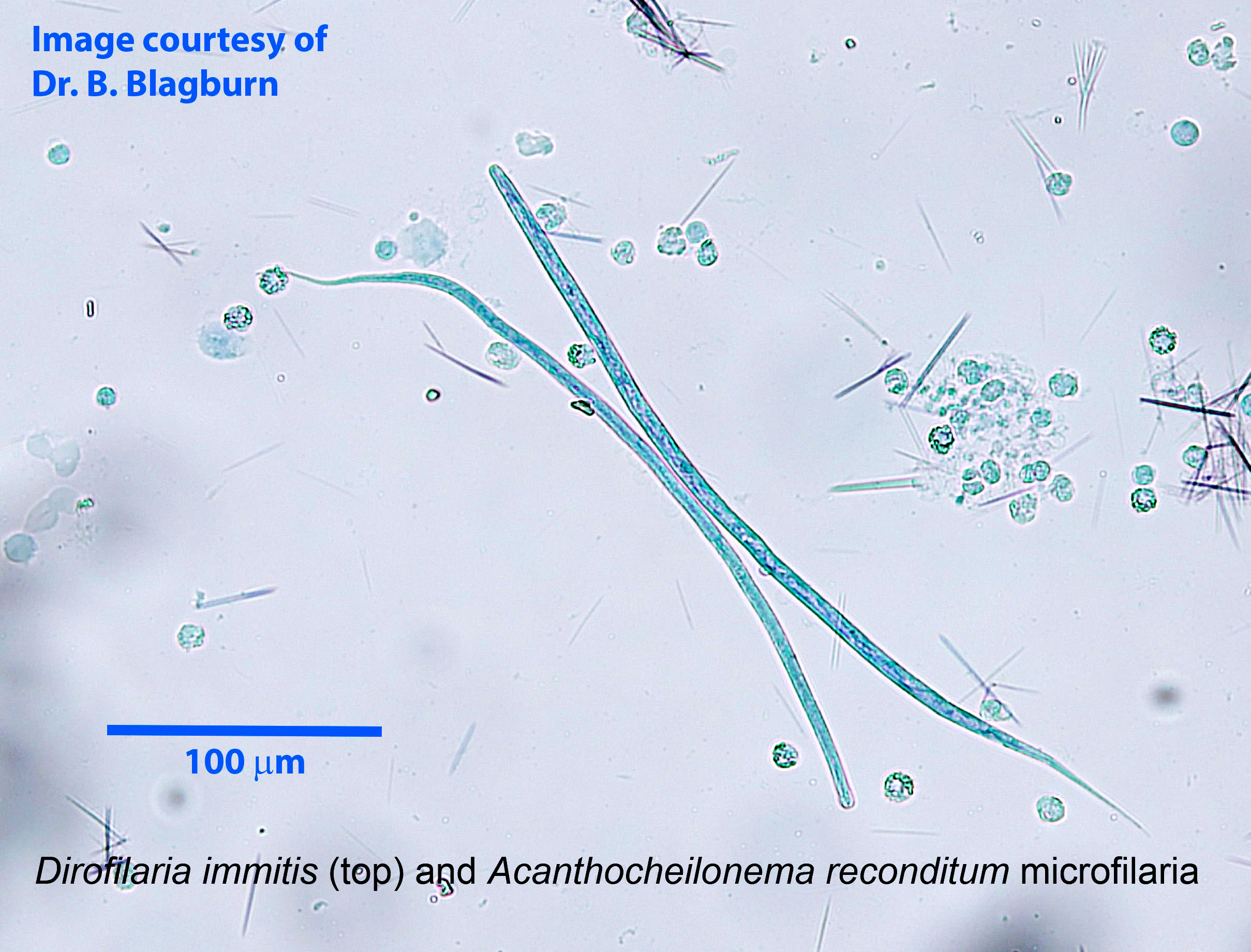

The microfilariae (first-stage larvae) released by adult female D. immitis are approximately 300 to 325 µm in length, with a tapered anterior end (“a hemisphere surmounting a cone”) and a long, thin, pointed tail (sometimes in the shape of a button hook). These can be distinguished from microfilaria of the skin dwelling nematode Dipetalonema (or Acanthocheilonema) reconditum, which have a blunt, or broomstick handle, head.

Host range and geographic distribution

In Canada the endemic areas are south-western Quebec, southern Ontario, areas of southern Manitoba, the southern Okanagan Valley in British Columbia (Osoyoos and Oliver and surrounding areas), and the Tracadie area of New Brunswick. The introduction of D. immitis to the Okanagan Valley of British Columbia is thought to have resulted from the movement of infected hunting dogs from Texas, the tethering of the dogs out-of-doors, the presence of multiple mosquito breeding sites and a reduction in local municipal mosquito control programs. There has been little recent evidence that transmission continues in light of widespread use of prophylaxis in the Okanagan.

In most of northern and western Canada are believed to have acquired the parasite in one of these endemic areas, or elsewhere. Dirofilaria immitis has been diagnosed very rarely in cats, and rarely in dogs in Canada. In a recent national study in Canada seroprevalence was 0.42% of 115,636.

It is likely that the geographic range and season of transmission of heartworm will increase in Canada as the climate continues to warm.

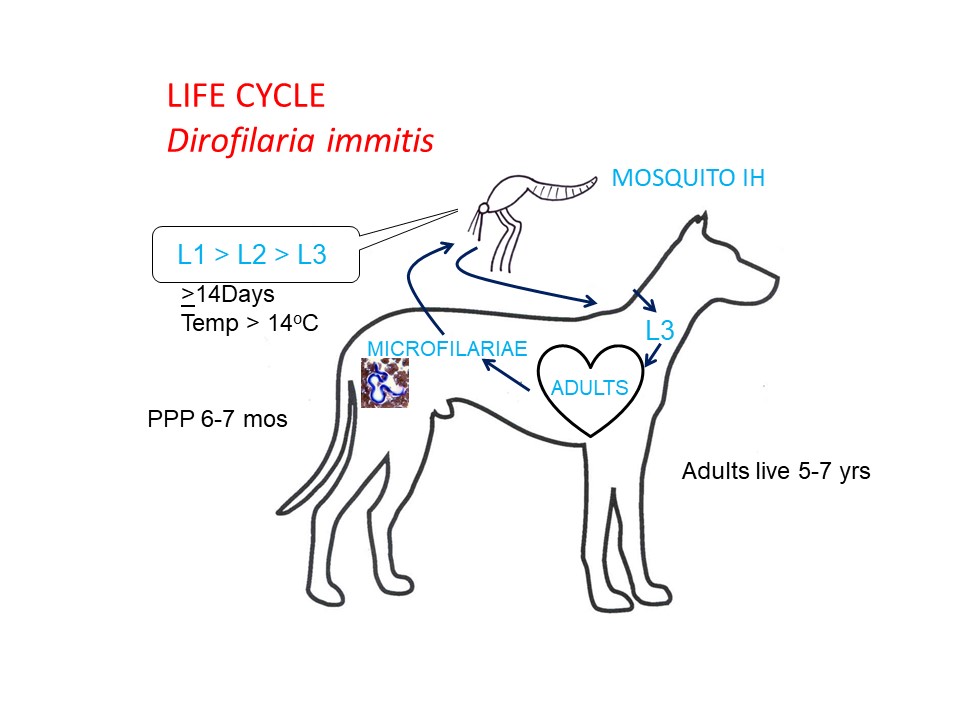

Life cycle - indirect

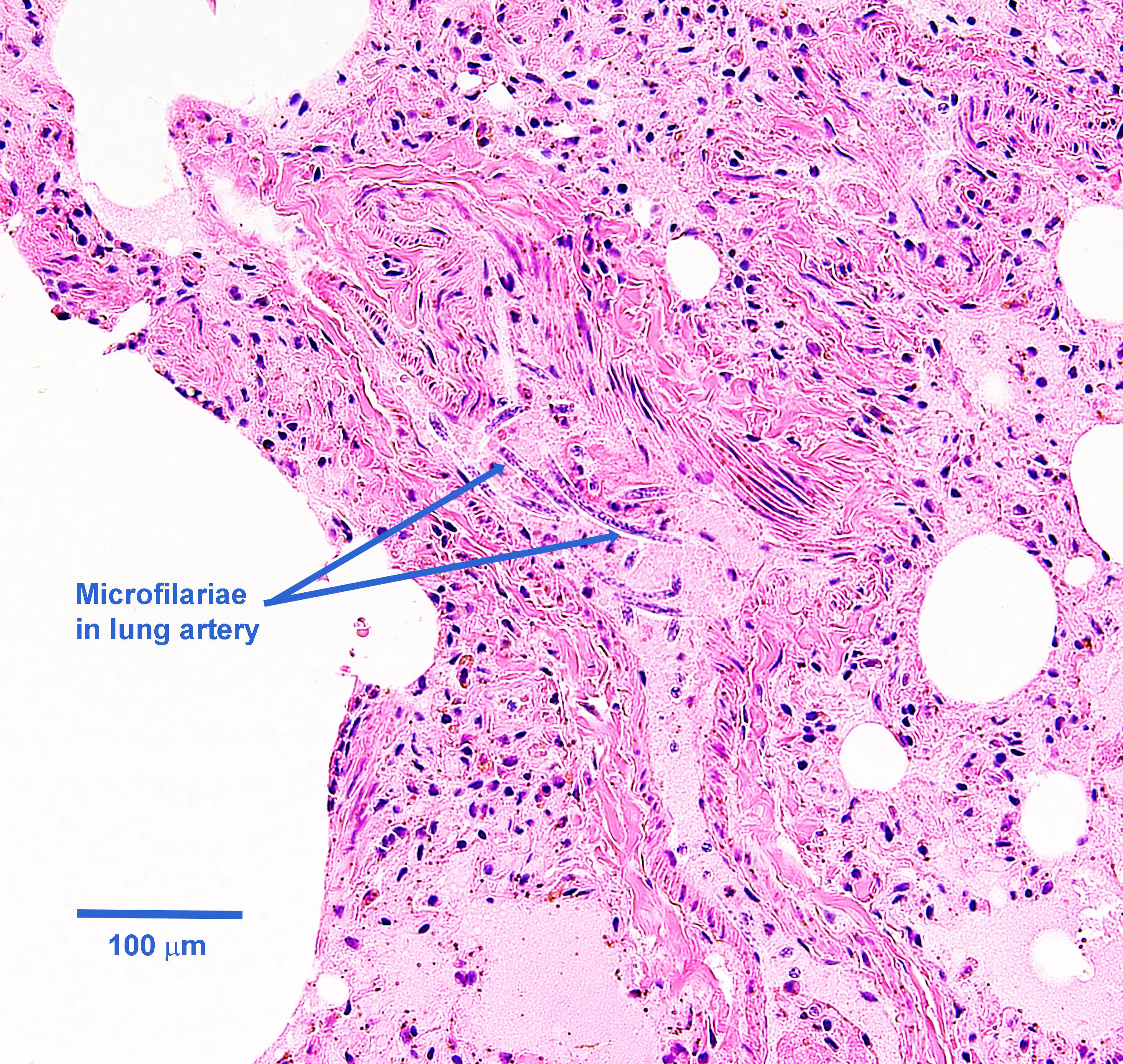

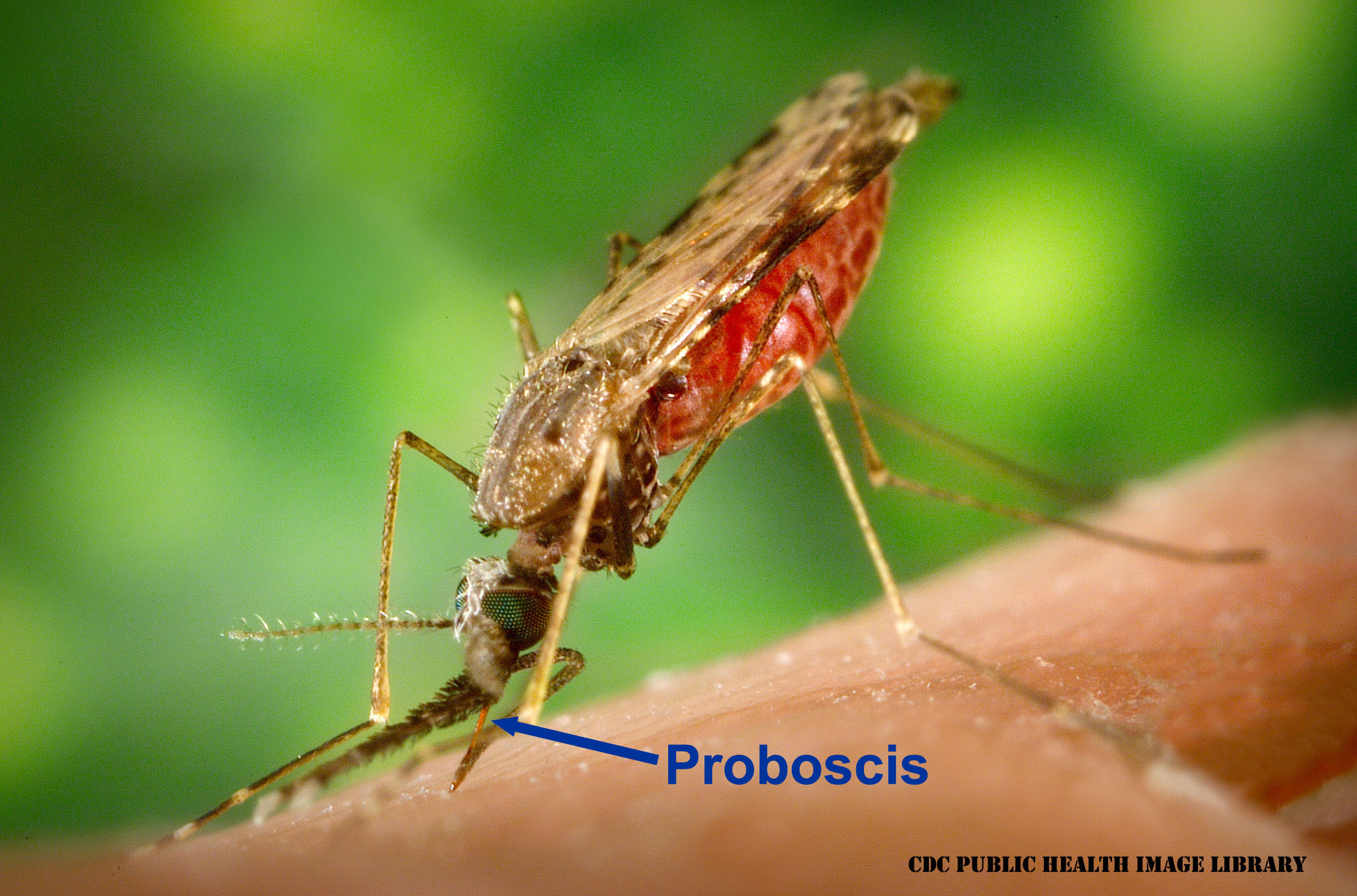

In the dog definitive host, adult D. immitis are located in the pulmonary artery and right ventricle (and rarely other sites). Microfilariae (first-stage larvae) are released into the blood. Following ingestion by a suitable female mosquito during blood-feeding, the microfilariae undergo two moults to become infective third-stage larvae which move to the mouthparts of the mosquito. Under ideal conditions (a constant 27C), approximately 14 days are required for development of the infective larvae in the mosquitoes. At a constant 18C, larvae require approximately one month to become infective. During a subsequent blood meal, the infective third stage larvae escape from the mouthparts and penetrate the skin of the dog, often through the wound made by the mosquito’s proboscis.

In the dog, the newly introduced larvae migrate in the sub-cutaneous connective tissue and by approximately 3 to 4 months after infection immature adults are present in the heart and pulmonary artery. The pre-patent period for D. immitis in dogs is 6 to 7 months, and adult parasites can survive for 5 to 7 years. Microfilariae can survive in dogs for up to two years in the absence of adult heartworm.

In cats, D. immitis rarely completes development to the adult stage and the infection is usually not patent. Immature parasites may be present in the heart and pulmonary arteries, but they are also common in other sites.

Epidemiology

Heartworm depends for successful transmission on: a) the presence of definitive hosts with patent infections; b) suitable species of mosquito intermediate hosts; c) environmental conditions that support the complete development of infective larvae in the mosquitoes; and d) sympatric populations of definitive and intermediate hosts at sufficient densities. In an area where there is actual or possible transmission of D. immitis, the parasite’s epidemiology is influenced by three key factors: the seasonality of transmission; the potential for asymptomatic carriers, including wildlife; and the application of heartworm preventatives. As well, normal development and survival of D. immitis relies on the rickettsial organism Wolbachia, an important endosymbiont of filarial nematodes.

Larval development in mosquitoes essentially stops at temperatures below 14C. This need for mosquitoes and the temperature sensitivity of larval development mean that heartworm transmission is strongly seasonal in Canada, i.e. 4-6 of the warmest months between May and October, versus year-round in the southern USA. Therefore, heartworm prophylaxis is only recommended during the warmer part of the year in Canada. Due to the long pre-patent period, there is a strong seasonality for testing (best conducted in May, at least 6 months after the last possible transmission, generally October in Canada).

Pathology and clinical signs

The pathology of heartworm infection and disease is associated directly with the intensity of adult parasites in the right ventricle and pulmonary artery. Among the possible lesions are endocarditis and endarteritis of the pulmonary arteries, the latter sometimes leading to pulmonary hypertension, which can result in hypertrophy of the right ventricle and congestive heart failure. Sometimes, particularly after adulticide treatment, the adult D. immitis disintegrate, and the fragments can cause pulmonary emboli, which can be very serious. The microfilariae have also been occasionally associated with lesions, particularly in the skin - where they cause pruritic nodules and/or eruptions. Parasite antigen/antibody complex deposition has been associated with glomerulonephritis and proteinuria.

Only a proportion of dogs infected with D. immitis are symptomatic. The severity of clinical signs depends on the adult heartworm burden and on the general health status of the dog. Clinical signs in dogs are associated with compromised pulmonary circulation, and include reduced exercise tolerance, coughing, anorexia, and weight loss. In severe heartworm disease, hepatomegaly and syncope may occur, and some cases may be fatal. Rarely in heavily infected dogs, adult heartworms may obstruct the tri-cuspid heart valve (between the right atrium and ventricle) and/or the posterior vena cava. This acute condition (caval syndrome) leads to severe hepatic congestion, a jugular pulse, haemoglobinaemia, haemoglobinuria and, if the parasites are not surgically removed, death. Caval syndrome is thought to be a particular risk when large numbers of heartworms mature over a short period of time, and to be less of a problem, therefore, where the prevalence and abundance of heartworm infection are low. (i.e. most of Canada)

In cats, presenting signs of D. immitis infection are non-specific and may be either acute or chronic. In the former, signs include dyspnoea, diarrhoea and vomiting, convulsions, syncope and sudden death; in chronic cases, coughing, vomiting, dyspnoea and lethargy are among the clinical signs observed.

Diagnosis

In dogs, history and clinical signs are helpful for heartworm diagnosis, but are not conclusive. In the past, a definitive ante-mortem diagnosis of heartworm infection was usually based on the detection of microfilariae in blood. More recently, a range of serological tests has been developed. Currently the serological "snap" tests most commonly used in Canada detect antigen produced by mature female heartworms. The specificity of these tests is very good (approaching or at 100%), as is the sensitivity - unless only immature females, or very few adult parasites, or only males, are present. Because these tests depend on the presence of mature, adult female heartworms, they will not detect infection during the pre-patent period, and testing should not be initiated until May six to seven months after the last possible exposure (generally October in Canada).

The optimal frequency of testing of dogs in endemic areas, or of animals that travel to endemic areas, is the subject of considerable debate. The American Heartworm Society is currently recommending annual testing for pets living in or traveling to endemic areas. Annual testing is recommended because owner (or pet) compliance with monthly prophylaxis should never be assumed to be 100%, because resistance to monthly preventatives is increasingly documented, there is some risk (anaphylaxis) to starting monthly prophylaxis in a dog with circulating microfilaria, and finally, many drug companies will not cover the high price of adulticide treatment if pets are not tested annually.

Outside endemic regions, there is little benefit, and some concern, to testing dogs with no clinical signs and no credible exposure history, since false positives are possible, especially in low prevalence regions (i.e. most of Canada)

When a positive serological test result is a surprise, for example in a dog with no credible exposure history, a common recommendation is to test the dog again using a new blood sample and adifferent test method. Conversely, a negative antigen test in an animal that has clinical signs of heartworm and a credible exposure history should be followed up with an additional serological test, and/or a microfilarial detection test. False negatives on antigen tests associated with the formation of antigen/antibody complexes are possible, and can be addressed in a diagnostic lab through heating the sample prior to testing. Whichever serological test is used, it is essential to ensure that the test procedure is carried out very carefully and exactly as described by the manufacturer in the instructions accompanying the test kits.

Microfilaria detection tests are rarely used now in North America because they do not detect occult heartworm infections (adult heartworms without circulating microfilariae) or very low numbers of microfilariae. If a microfilaria detection test is to be done, the best is the modified Knott test, in which anticoagulant-treated blood is lysed with 2 percent formaldehyde, centrifuged, and the deposit stained with methylene blue prior to microscopic examination. In addition, blood samples should be taken in late afternoon and early evening, when vectors are most active and microfilaria most likely to be circulating.

In cats, because D. immitis infection is usually non-patent, microfilaria and antigen detection tests are not helpful. More useful for determining exposure to heartworm in cats are tests that detect antibodies to pre-adult and adult parasites, but because of poor sensitivity, interpretation of the results from these tests is difficult. For both dogs and cats, other diagnostic procedures for D. immitis, including radiology, ultrasonography and angiography may be helpful.

For any suspected case of heartworm disease diagnosis should ideally be based on the assembly of diagnostic data from several different sources, including the animal's travel history,prevalence of the parasite in the regions where the animal lives or has traveled to, us of prophylaxis, the local resistance to monthly preventatives and the known limitations of the test(s) being used.

Treatment and control

Dirofilaria immitis in Dogs - Preventatives

Heartworm prophylaxis should be used in dogs which live in or travel to heartworm endemic regions during the mosquito active season. They should not be routinely administered in most of western Canada, nor should they be used for blanket prophylaxis of gastrointestinal nematodes due to increasing concerns about resistance. Several macrocyclic lactones are labeled for use in Canada, including iIvermectin,milbemycin, moxidectin, and selamectin. These drugs are administered monthly, except for parenteral moxidectin, which is administered every six months to kill larvae introduced by the mosquitoes for six months following administration of the drug. The monthly preventatives function by killing third-stage larvae of D. immitis introduced by the mosquito into the dog during the month preceding administration of the preventative (“reach-back” effect). Thus in Canada the first monthly preventative should be given in June, one month following the first possibility of exposure (May) and continued unti November, one month after the last possibility of exposure (October).

All dogs being placed on a preventative for the first time should be tested in advance for heartworm using an antigen test. If this test is negative, then the preventative can be started. If the test is positive, the heartworm status of the dog should be assessed further. In dogs with large numbers of circulating microfilariae there is a very slight risk of a systemic reaction in the hours following the first administration of a macrocyclic lactone preventative; the reaction is thought to be associated with the death of the microfilariae.

For dogs normally resident in an area that is non-endemic for heartworm but traveling to an endemic area for a short time (up to two weeks), a single dose of a monthly preventative as soon as they return home (and not later than three weeks after return) will kill any D. immitis third stage larvae that they have acquired during their trip.

Resistance to the macrocyclic lactone preventatives for heartworm is increasingly documented in the USA. The emergence of this drug resistance has called into question the wide-spread use of macrocyclic lactones, especially in regions where heartworm is absent or at very low prevalence (i.e. most of western Canada). It has also led to recommendation against the "slow kill" method in lieu of adulticide therapy; i.e.use of a monthly heartworm preventive to suppress microfilaria without treating the adult nematodes. This should only be considered as a salvage procedure in animals that cannot tolerate adulticide therapy. Finally, importation of dogs from regions where resistant heartworm is known to be present is strongly discouraged.

Aldulticides

Melarsomine is the adulticide currently used in Canada.The drug is administered by deep intramuscular injections. Pre-treatment evaluation of the dog is essential, with particular attention given to the severity of the D. immitis infection and to cardio-pulmonary function. In areas of ongoing heartworm transmission, a macrocylic lactone preventative can be given for up to six months prior to adulticide therapy in an effort to reduce the parasite burden to be treated. The most serious complication of adulticide therapy is severe pulmonary thromboembolism, which may be fatal, and is why strict cage rest is strongly recommended following adulticide treatment. The efficacy of adulticide treatment can be assessed using an antigen test six months after the completion of the treatment, by which time the antigen should no longer be present in a successfully treated dog.

Because of the association between D. immitis and Wolbachiapre-adulticide treatment with doxycycline, with or without ivermectin, seems to reduce the severity of arterial lesions and significantly reduce thrombus formation following melarsomine adulticide treatment.

In dogs that are positive for heartworm, the American Heartworm Society currently recommends initial stabilization (glucocorticosteroids, diuretics, vasodilators, fluids, oxygen) if clinically indicated, followed by:

–Day 1: macrocyclic lactone (ML) as microfilaricide

–Days 1-28: doxycycline 10 mg/kg BID

–Day 30: macrocyclic lactone (ML) as microfilaricide

–Day 60: ML, initial dose melarsomine, prednisone, cage rest

–Day 90: ML, second dose melarsomine, prednisone, cage rest

–Day 91: third dose melarsomine; restrict exercise 6-8 wks

Microfilaricides

Without treatment, microfilariae can persist for up to two years in the absence of adult parasites (melarsomine only kills adults), and be a source of D. immitis infection for mosquitoes. Treatment of confirmed cases with an adulticide and a microfilaricide removes the treated dog as a source of infection for mosquitoes. In Canada, ivermectin and milbemycin are the two drugs used (extralabel) to remove circulating microfilariae. Treatment can start as soon as heartworm is diagnosedand the drugs given monthly or fortnightly. Milbemycin causes a very rapid drop in numbers of microfilariae in the hours following the initial treatment. Dogs on this drug should be watched, therefore, for signs of a systemic reaction, usually characterised by a variety of clinical signs, including lethargy, salivation, vomiting and tachycardia.

Dirofilaria in Cats

Preventatives

Milbemycin, moxidectin and selamectin are approved in Canada as heartworm preventatives for cats. Given the low prevalence in Canada, there is little indication of a need for heartworm prophylaxis in cats, especially indoor cats. Melarsomine cannot be used in cats.

Public health significance

References

Blagburn BL et al (2011) Comparative efficacy of four commercially available preventive products against the MP3 laboratory strain of Dirofilaria immitis. Veterinary Parasitology 176: 189-194.

Kramer L et al. (2011) Evaluation of lung pathology in Dirofilaria immitis-experimentally infected dogs treated with doxycycline or a combination of doxycycline and ivermectin before administration of melarsomine dihydrochloride. Veterinary Parasitology 176: 357-360.

Bowman DD et al. (2009) Heartworm biology, treatment and control. Veterinary Clinics of North America Small Animal Practice 39: 1127-1158.

Herrin BH et al. (2017) Canine infection with Borrelia burgdorferi, Dirofilaria immitis, Anaplasma spp. and Ehrlichia spp. in Canada, 2013–2014. Parasites and Vectors 10: 244 https://parasitesandvectors.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13071-017-2184-7

Lister AL et al. (2008) Feline heartworm disease:a clinical review. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery 10: 137-144.

McCall JW et al. (2007) Heartworm disease in humans and animals. Advances in Parasitology 66: 193-285.

https://research-groups.usask.ca/cpep/parasitedata/western-canada.php

https://research-groups.usask.ca/cpep/parasites/heartworm-supplementary.php

https://www.heartwormsociety.org/images/pdf/2018-AHS-Canine-Guidelines.pdf