Echinococcus canadensis

The cestode genus Echinococcus contains at least seven established species, two of which (Echinococcus canadensis and E. multilocularis) occur in Canada.

Summary

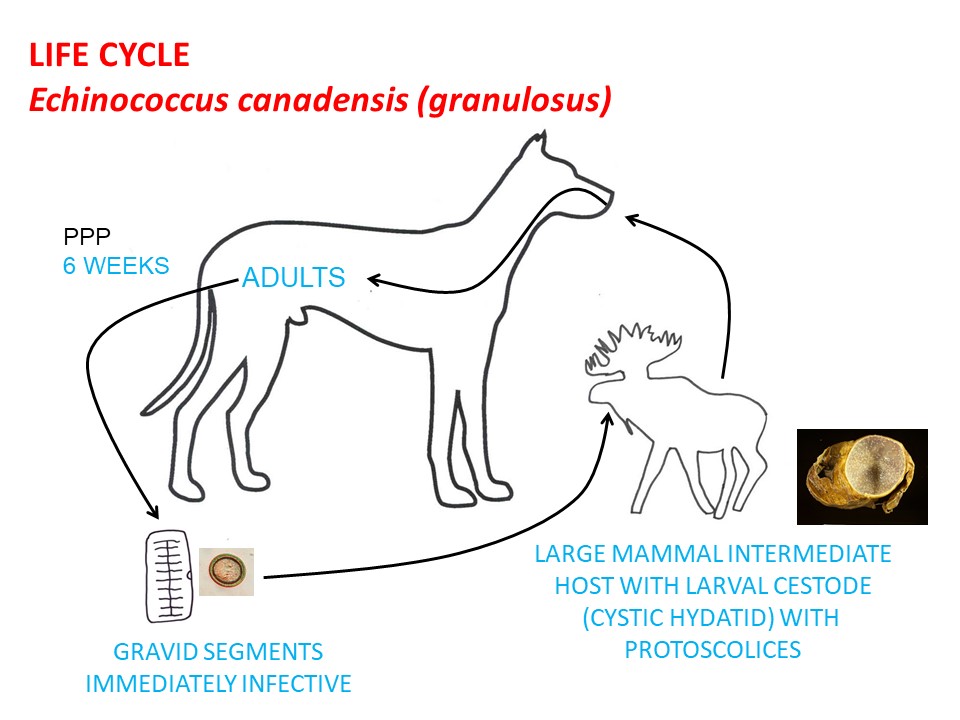

In Canada Echnicoccus canadensis (also known as the G8 and G10 cervid genotypes of E. granulosus) cycles between wild canids (wolves, coyotes, and fox) and cervids (moose, caribou, elk, and deer), occasionally spilling over into dogs (as definitive hosts) and people (as aberrant intermediate hosts). This parasite is present across Canada wherever wildlife hosts are established, with the current exception of the island of Newfoundland. Adult E. canadensis ar tiny tapeworms (<1cm long) that live in the small intestine of the canid definitive host. Eggs passed in the feces, or in gravid segments in feces are environmentally resistant and immediately infectective for herbavore intermediate hosts.In the intermediate host, the parasite develops to a hydatid cyst, usually in the lungs. The next definative host is infected by ingestion of the hydatid cyst (or metacestode) in the organs of intermediate hosts.

In the definitive host, adult E. canadensis are very rarely associated with clinical signs, but cystic echinococcosis (CE) in the intermediate hosts can cause significant pathology, and in wildlife increase the risk of predation by reducing pulmonary function. Diagnosis in dogs is best accomplished by coproPCR, either as a screening tool in a high risk dog (one with access to cervid carcasses), or following detection of taeniid-type eggs in feces. Control is best accomplished by preventing dogs from having access to cervid carcasses, treating dogs with praziquantel within 4-6 weeks of potential exposure, freezing or cooking game meat and organs prior to feeding to dogs, good hand hygiene and pooper-scooping, and prevention of human consumption of unwashed produce or unfiltered surface water in areas where infected dogs or wild canids may have defecated.

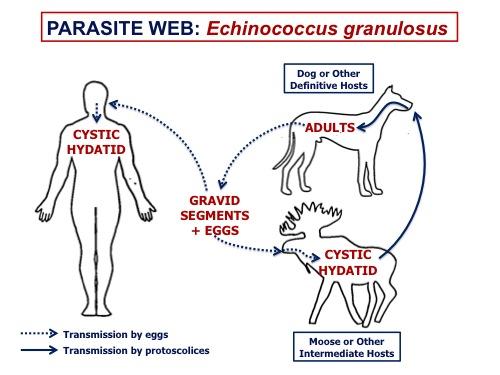

Echinococcus canadensis can infect people following ingestion of infective eggs from the feces of a definitive host, but not directly from consumption of cysts in organs from cervids. For E. canadensis the cystic hydatid develops most commonly in the lungs. In other areas of the world, E. granulosus cycles between dogs and livestock, causing CE primarily in the liver. Cystic echinococcus is now relatively rare in Canada and often acquired elsewhere.

Taxonomy

Class: Cestoda

Order: Cyclophyllida

Family: Taeniidae

Adult tapeworms of the family Taeniidae (Taenia and Echinococcus) tend to be parasites of carnivores and omnivores and produce “taeniid” type eggs that cannot be distinguished morphologically. They cycle between carnivore definitive hosts and herbivore intermediate hosts, in naturally occuring predator-prey assemblages around the globe.

In Canada only E. multilocularis and E. canadensis (sometimes referred to as the cervid genotypes of the E. granulosus species complex) are established. Both G8 and G10 genotypes of E. canadensis are present in cervids and canids in Canada. Species/genotypes that circulate between dogs and livestock are not thought to be present in Canada, although E. granulosus sensu stricto (G1 genotype) may be present in sheep in the western USA, and there are rare reports of E. equinus in horses in the USA.

Morphology

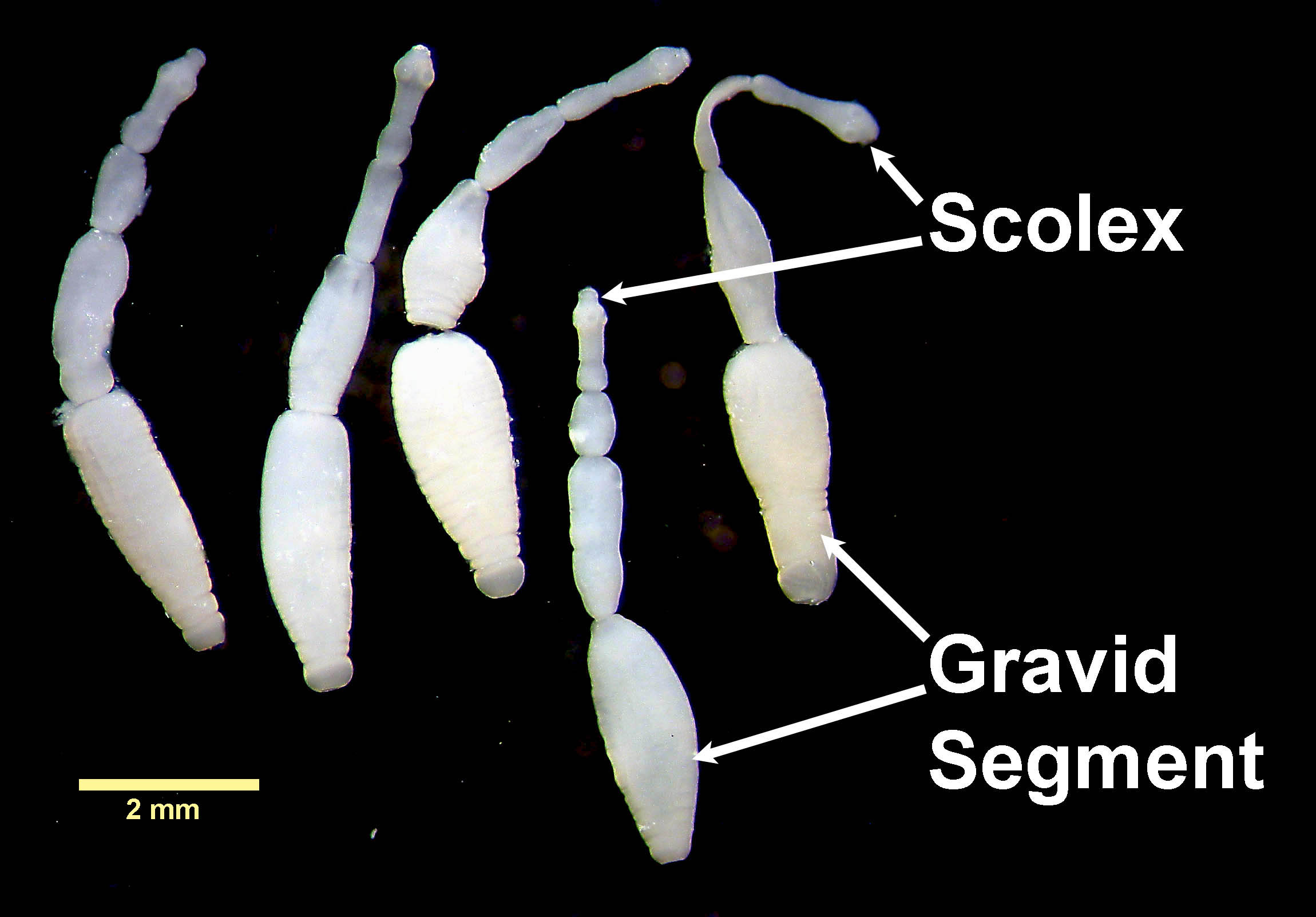

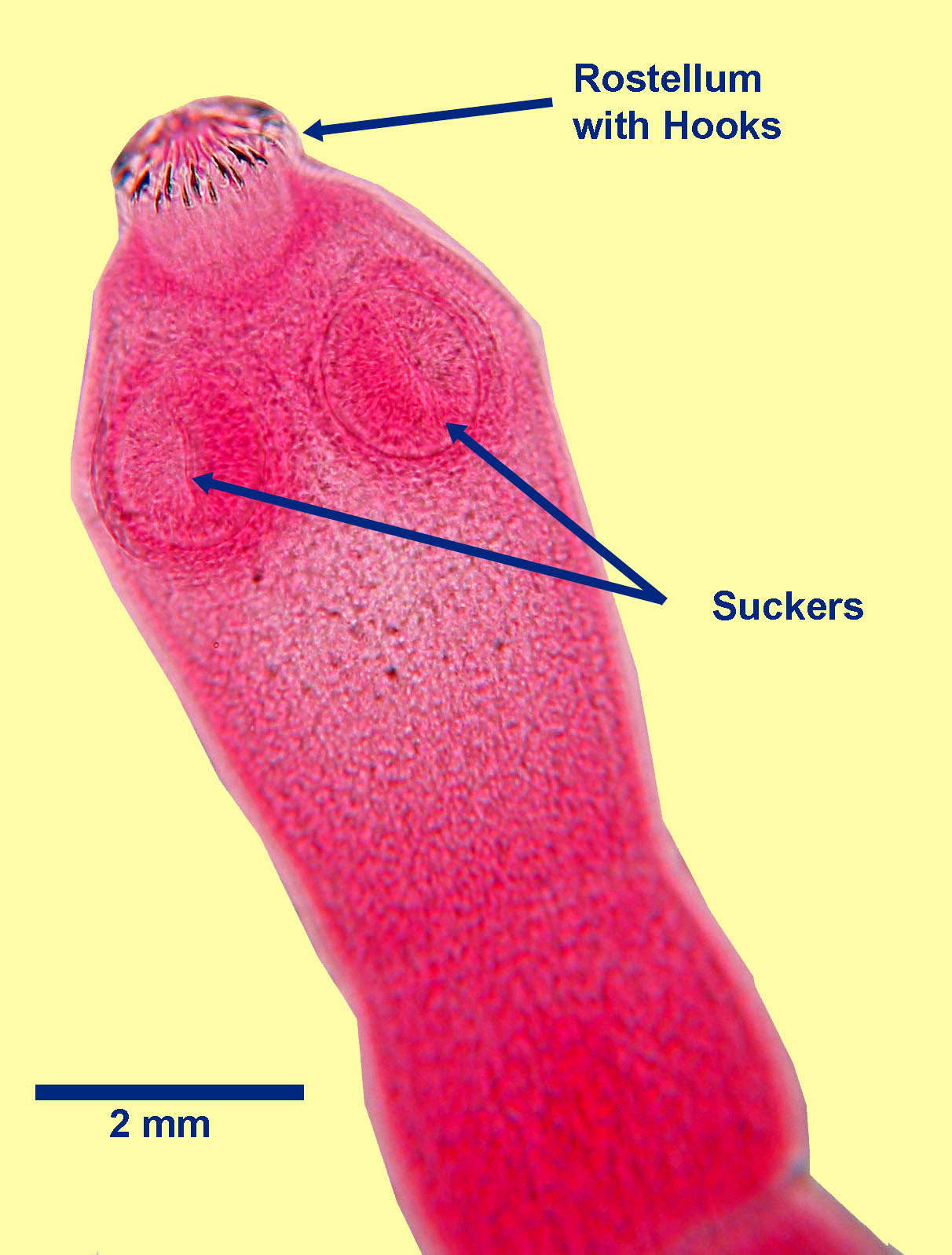

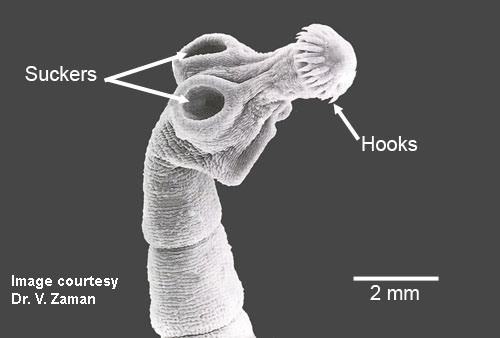

Adult E. canadensis are small (less than 1 cm long and only a few segments) and have an anterior scolex (attachment or holdfast organ), behind which is the very short, segmented body. At the anterior tip of the scolex is a rostellum, which is armed with two circles of hooks. Behind the rostellum are four circular, muscular suckers. Each mature segment of E. candensis contains a single set of reproductive organs, with a lateral genital pore in the caudal half of the mature segment. In most specimens of E. canadensis, even those that have been fixed and stained, the uterus, the genital pore, and the testes, are often the only visible reproductive structures. Mature adult E. canadensis can be distinguished microscopically from adult E. multilocularis by their larger size and the position of the lateral genital pore (anterior to the mid point in E. multilocularis) and its relationship to the testes (extend anterior to the genital pore in E. granulosus).

Taeniid-type eggs of E. canadensis are round to oval, measure approximately 30 to 35 µm in diameter and have a thick, radially striated shell. Each egg contains a hexacanth larva with six hooks, not all of which are visible in every egg. The eggs of the various species of Echinococcus cannot be distinguished microscopically from each other, or from the eggs of the various species of Taenia.

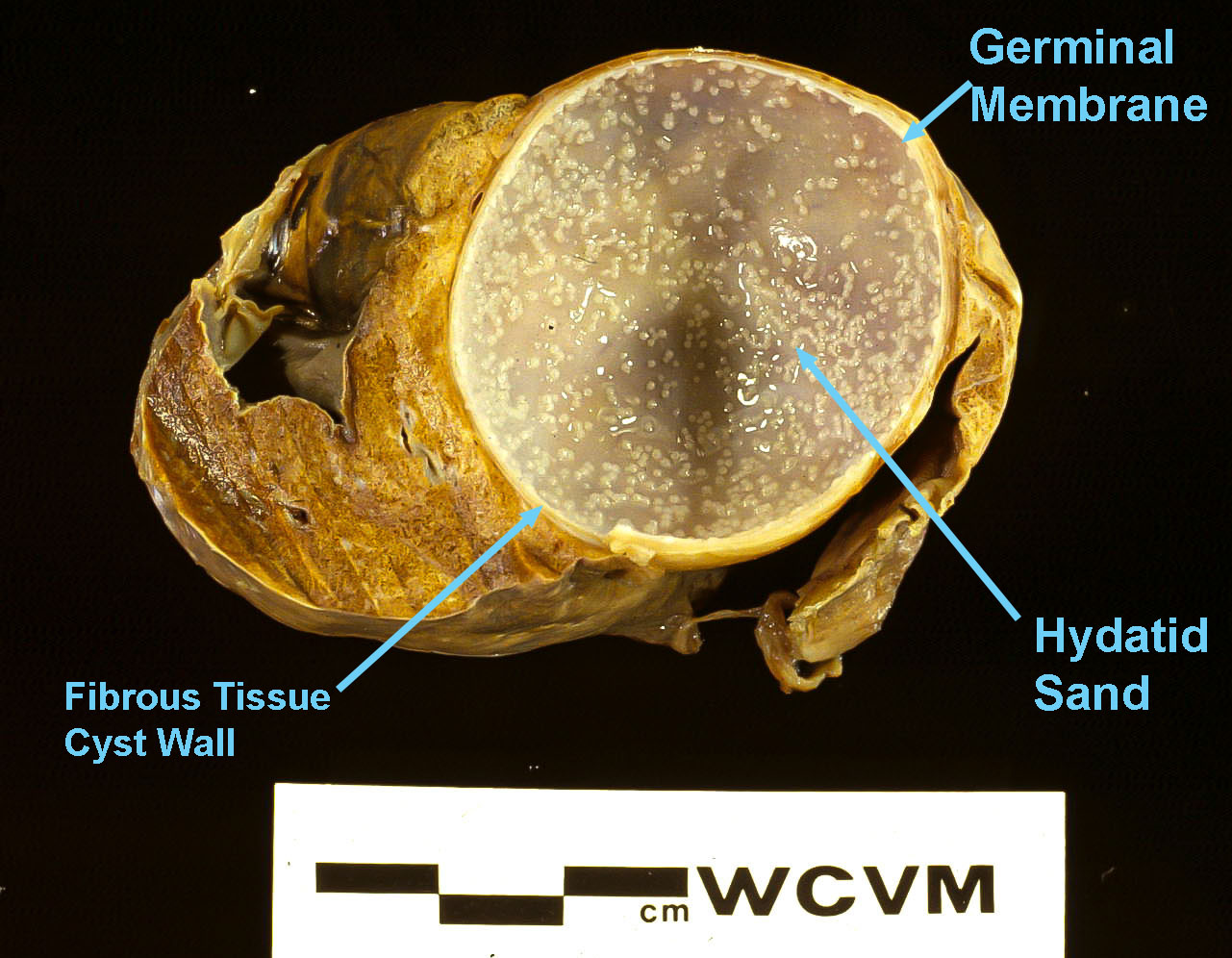

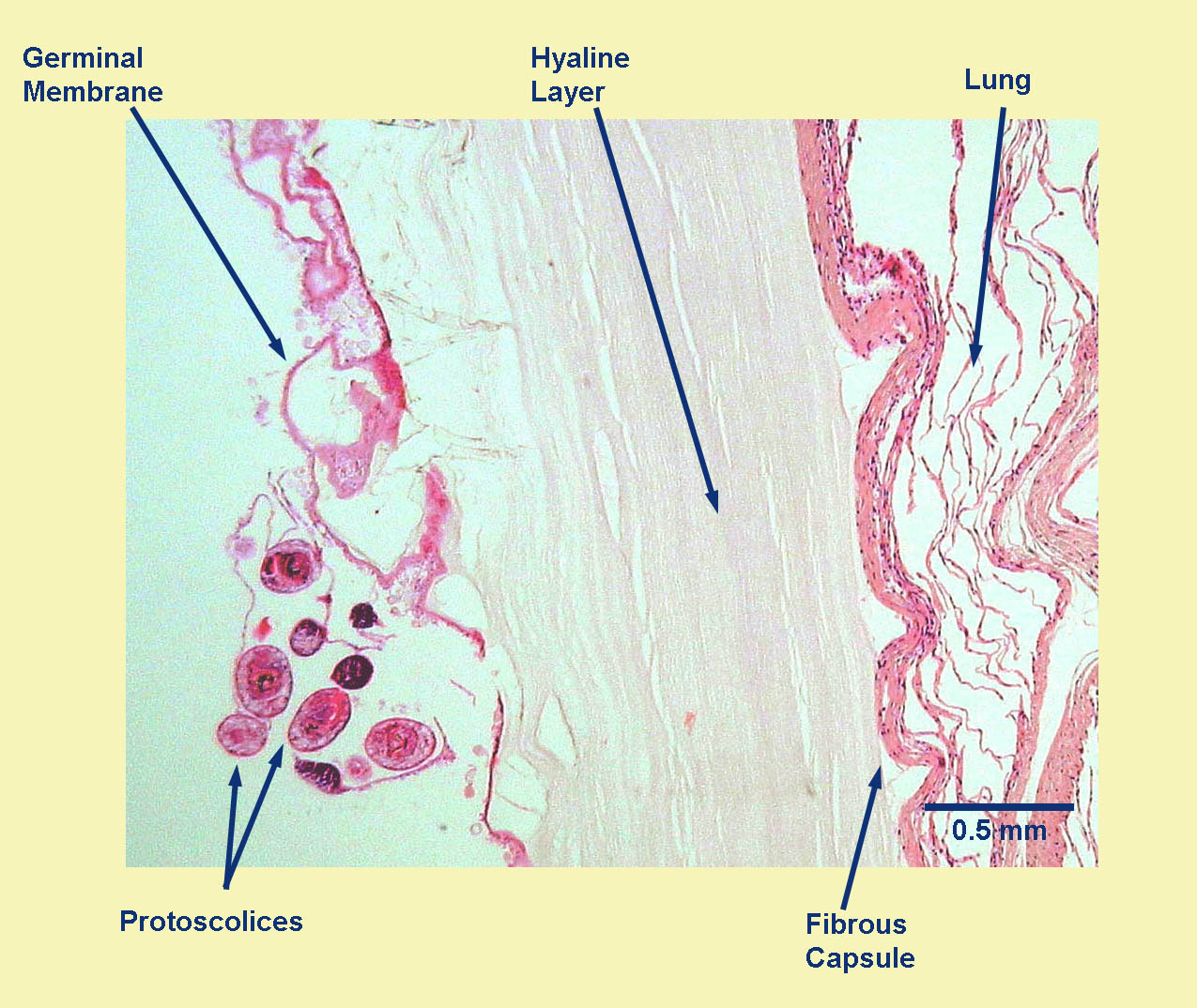

In herbivore intermediate hosts, the metacestode, or larval stage, takes the form of a cystic hydatid, or hydatid cyst, which is a thick-walled, discrete, fluid-filled structure (ranging from 1 mm to 20 cm in diameter) containing multiple (1000s) of protoscolices which may be free-floating or clump together to form hydatid sand.

Cysti

Cystic hydatid in IH

Cyst Wall Section Protoscolices from Hydatid cyst

Host range and geographic distribution

The larval stage (unilocular hydatid cyst) of E. canadensis can infect people, and this condition (cystic hydatid disease) is seen occasionally in Canada. Some of these infections were acquired outside the country, but some are autochthonous (locally acquired).

Echinococcus canadensis is present across Canada and parts of the USA, wherever suitable wildlife hosts are present (especially wolves). It was historically absent from the Atlantic provinces, where wolves had been extirpated, but the life cycle appears to be newly enabled between moose and coyotes in Nova Scotia. The island of Newfoundland remains, at moment, free of the parasite, but this may change with establishment of coyotes.

Life cycle - indirect

Adult E. canadensis live in the small intestine of the definitive hosts and, like all cestodes of veterinary importance, are hermaphrodites. Gravid segments (or whole parasites) containing large numbers of eggs, pass intact in the feces or disintegrate in the GI lumen, releasing the eggs, which are also passed in the feces. If an egg is ingested by a suitable herbivore intermediate host (required for completion of the life cycle) the egg hatches in the stomach. The released hexacanth larva then invades the GI wall and migrates in the bloodstream to various tissues, where it develops into the larval stage infective for definitive hosts over several months. For E. canadensis, this larval stage is the cystic hydatid. For E. canadensis, the lungs are the usual site of cystic hydatids in the intermediate host. For other species and strains of E. granulosus, the liver is most often affected. The life cycle continues when the hydatid cyst in the organs of the intermediate host is eaten by a suitable definative host. Here, the wall of the unilocular hydatid cyst disintegrates and the protoscolices are released, evert to for a scolex, and attach to the mucosa of the small intestine, producing segments and completing their development to adult tapeworms. Adult tapeworms live about 6 months and the prepatent period is about 6 weeks.

Epidemiology

As for many parasites, prevalence and intensity of Echinococcus spp. in canid definitive hosts may be higher in young animals; however, there is no evidence that canids develop protective immune responses and therefore older animals can easily be re-infected. In Canada, dogs who are free-ranging in remote and rural regions and have access to cervid carcasses, or are fed raw meat and organs from cervids, are at high risk of exposure to Echinococcus. Unlike Taenia species tapeworms, individual E. canadensis do not produce large numbers of eggs. Compensating for the low levels of egg production,definitive hosts can harbour thousands of adult cestodes, and a single egg of E. canadensis can produce very large numbers of protoscolices as a cystic hydatid in the intermediate host. Eggs of E. canadensis are immediately infective and environmentally resistant. They survive months to years in the environment, freezing at -20C, and exposure to most disinfectants and fixatives (including ethanol and formalin). They are inactivated by heat (>60C for 5 minutes), freezing at or below -70 C for at least 48 hrs, desiccation, and strong bleach solutions. Hydatid cysts in organs of intermediate hosts can be inactivated by freezing at -20C for at least 3 days, or by cooking. Protoscolices in hydatid cysts can survive a few weeks in carcasses at temperatures above freezing, enabling transmission via scavenging

Pathology and clinical signs

Diagnosis

Treatment and control

Praziquantel is the drug of choice for Echinococcus species in carnivores. The larval stages in domestic and free-ranging herbivores are not treated.The primary goal of treatment in dogs is to halt environmental contamination with eggs for public health considerations, since the parasite poses little concern for canine health. Wherever possible, dogs should not have access to cervid carcasses or offal. If fed to dogs, organs from wild game can be frozen solid (for at least 3 days) or cooked thoroughly. High risk dogs (with a history of cervid consumption) should be dewormed within 4-6 weeks of known exposure, or monthly, especially if also in a region where E. multilocularis is present. In Canada, a dog with taeniid eggs on fecal flotation should be treated with praziquantel and assumed to be high risk for exposure to Echinococcus, as it must have access to raw meat or organs of wildlife or sheep. A dog with confirmed Echinococcus spp. infection (i.e. positive coproPCR or morphological identification of gravid segments) should be treated with praziquantel and confined for 3 days, as eggs may be shed for 3 days post treatment. Given the public health considerations, it would also be appropriate to advise the owner to consult their health care provider, and to use extra care when pooper-scooping.

Public health significance

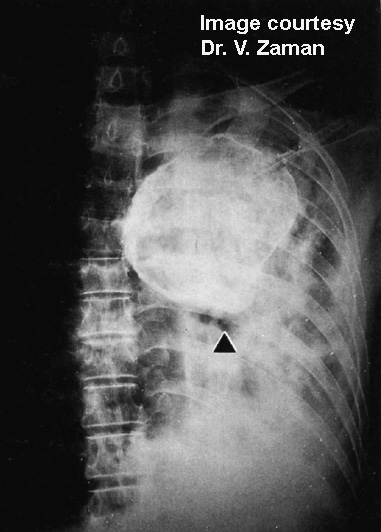

People are in the intermediate host position in the life cycle. If people ingest eggs of E. canadensis from carnivore feces, or contaminated produce or surface water, they can develop a cystic hydatid in various organs and tissues, primarily the lungs in Canada. People cannot be infected by consuming hydatid cysts in the organs of harvested cervids. Instead, the risk is from allowing dogs to consume these cysts, leading to contamination of the shared environment from eggs passed in dog feces. It is not clear how much transmission occurs directly from wild canids to people (presumably through consumption of unwashed produce or unfiltered surface water in areas contaminated by wild canid feces), or from dogs directly to people (i.e. from eggs adhering to dog fur from rolling in canid feces, or adhering to the perianal region in dogs with intestinal infections). Cystic echinococcosis (or CE) in people can be a significant clinical problem when the cysts grow too large, rupture (causing anaphylaxis and/or seeding with protoscolices), or establish in sensitive locations, like the brain.The incidence of this condition in people in Canada has declined significantly over the past fifty years, although cases are still diagnosed in northern residents (often as an incidental finding during thoracic imaging), and in immigrants from countries where the parasite is more common. In other parts of the world, the risk to human health has resulted in the implementation of comprehensive control programs, often with notable success.

Human patient with a Cystic Hydatid

References

Deplazes P et al. (2017) Global distribution of alveolar and cystic echinococcosis. Advances in Parasitology 95: 315-493 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/bs.apar.2016.11.001

Foreyt WJ et al. (2009) Echinococcus granulosus canadensis granulosus in grey wolves and ungulates in Idaho and Montana, USA. Journal of Wildlife Diseases 45: 1208-1212.

Himsworth CG et al. (2010) Emergence of sylvatic Echinococcus granulosus as a parasitic zoonosis of public health concern in an indigenous community in Canada. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 82: 643-645.

Jenkins E (2017) Echinococcus spp. tapeworms in dogs and cats. Clinician's Brief 15(7):14-18. https://www.cliniciansbrief.com/article/echinococcus-spp-tapeworms-dogs-cats.

Schurer J et al. (2018) Echinococcus in wild canids in Québec (Canada) and Maine (USA). PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases 12(8): e0006712. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0006712

Villeneuve, A et al (2015) Parasite prevalence in fecal samples from dogs and cats across the Canadian provinces. Parasites and Vectors 8:281 doi:10.1186/s13071-015-0870-x