Echinococcus multilocularis

The cestode genus Echinococcus contains at least seven established species, two of which occur in Canada: Echinococcus canadensis and E. multilocularis.

Summary

In the definitive host, adult E. multilocularis are very rarely associated with clinical signs, but AE is a severe, often fatal disease, starting in the liver and spreading throughout the peritoneum and elsewhere in the body.

Diagnosis of canine AE should be suspected on detection of a liver mass, especially in a young dog in a highly endemic region. Definitive diagnosis relies on detection of protoscolices or parasite material on biopsy or cytology; PCR on tissue, aspirated abdominal fluid, or cyst contents; or serology (not commonly available in Canada at moment). Prognosis is poor if not detected early and treated aggressively, generally involving long term chemotherapy with albendazole plus or minus surgical debulking. Although rare, dogs with AE may also harbor intestinal infections and this, not AE, may pose a risk to the owner or veterinary staff. Diagnosis of intestinal infections in dogs is best accomplished by coproPCR, either as a screening tool in a high risk dog (one with AE, or access to wild rodents in endemic regions), or following detection of taeniid-type eggs in feces in a region endemic for E. multilocularis (most of western Canada). Control is best accomplished by preventing dogs from having access to wild rodents (how dogs get intestinal infections), preventing dogs from eating feces of wild canids or other dogs (how dogs get AE), monthly treatment of high risk dogs with praziquantel, good hand hygiene and pooper-scooping, and prevention of human consumption of unwashed produce or unfiltered surface water in areas where infected dogs or wild canids may have defecated.

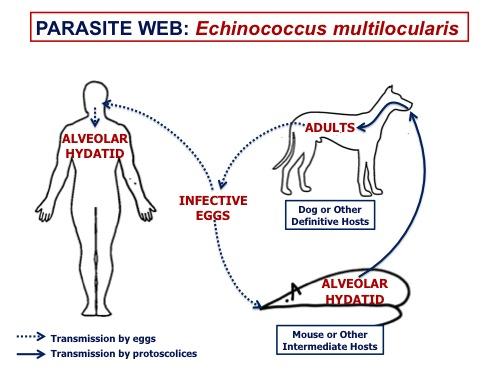

Echinococcus multilocularis can infect people following ingestion of infective eggs from the faeces of a definitive host, but not from contact with dogs or rodents with AE. Autochthonous human AE was almost unheard of in Canada, but now seems to be emerging in people in western Canada, particularly Alberta, possibly as a result of introduced European strains of the parasite which seem to be more likely to cause canine and human AE than strains previously established in North America

Taxonomy

Class: Cestoda

Order: Cyclophyllida

Family: Taeniidae

Adult tapeworms of the family Taeniidae (Taenia and Echinococcus spp.) tend to be parasites of carnivores and omnivores, and produce “taeniid” type eggs that cannot be distinguished morphologically. They cycle between carnivore definitive hosts and herbivore intermediate hosts, in naturally occuring predator-prey assemblages around the globe. Echinococcus multilocularis has a global distribution in the northern hemisphere. . Several genotypes have been identified within the species E. multilocularis, including distinct groups from Asia (group A - also pr/esent on St Lawrence Island, Alaska), Europe (E), and North America (N1 from St Lawrence Island, and N2 from central North America).

Morphology

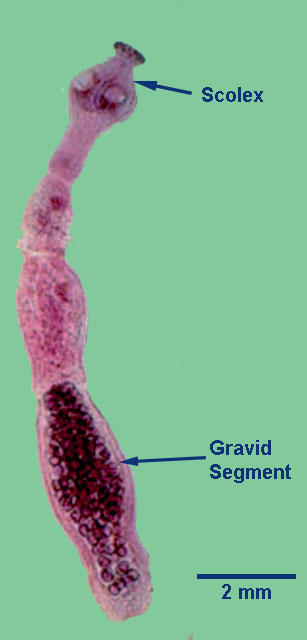

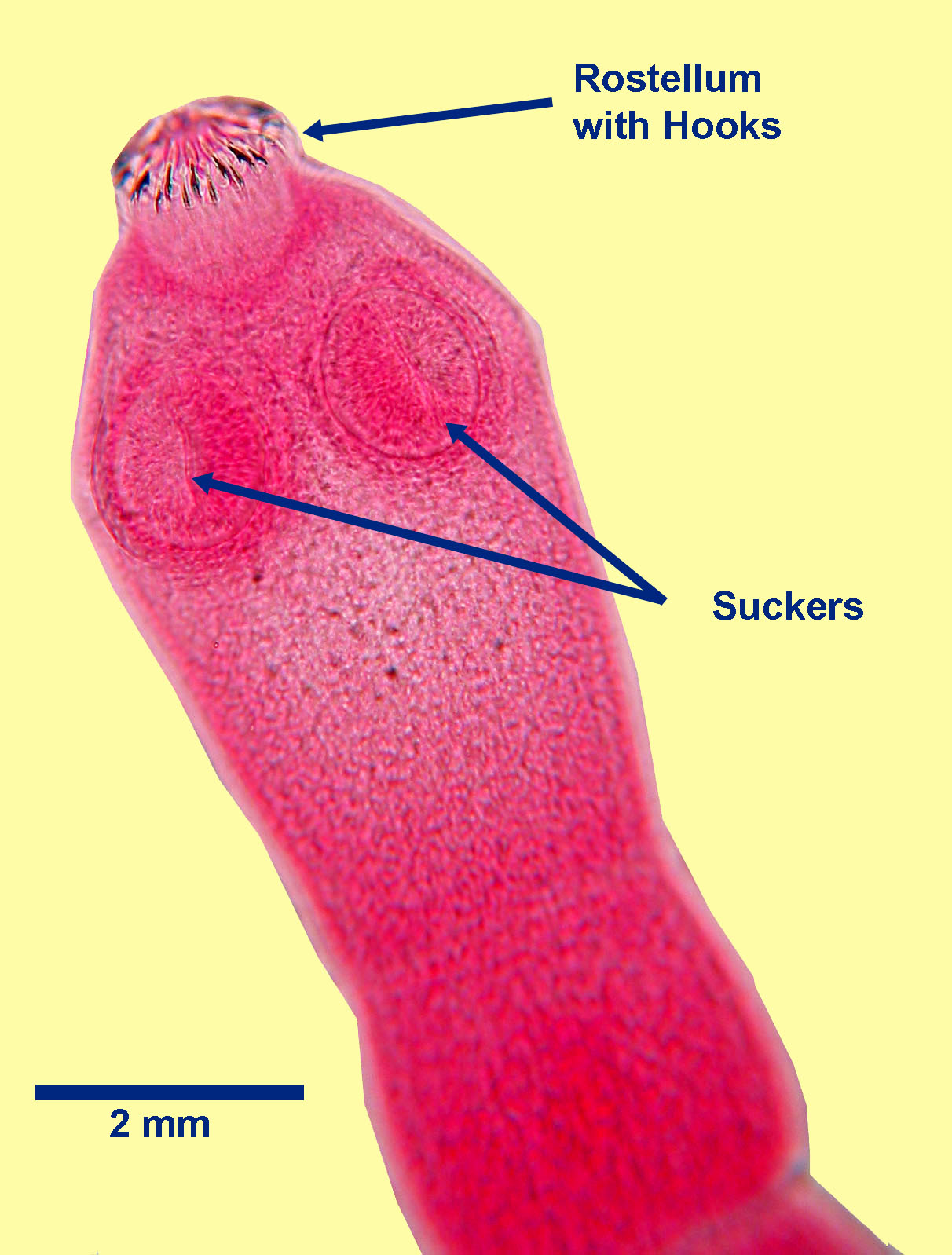

E. multilocularis scolex

Taeniid type eggs of E. multilocularis are round, measure approximately 30 to 35 µm in diameter and have a thick, radially striated shell. Each egg contains a hexacanth larva with six hooks, not all of which are visible in every egg. The eggs of the various species of Echinococcus cannot be distinguished microscopically from each other, or from the eggs of the various species of Taenia.

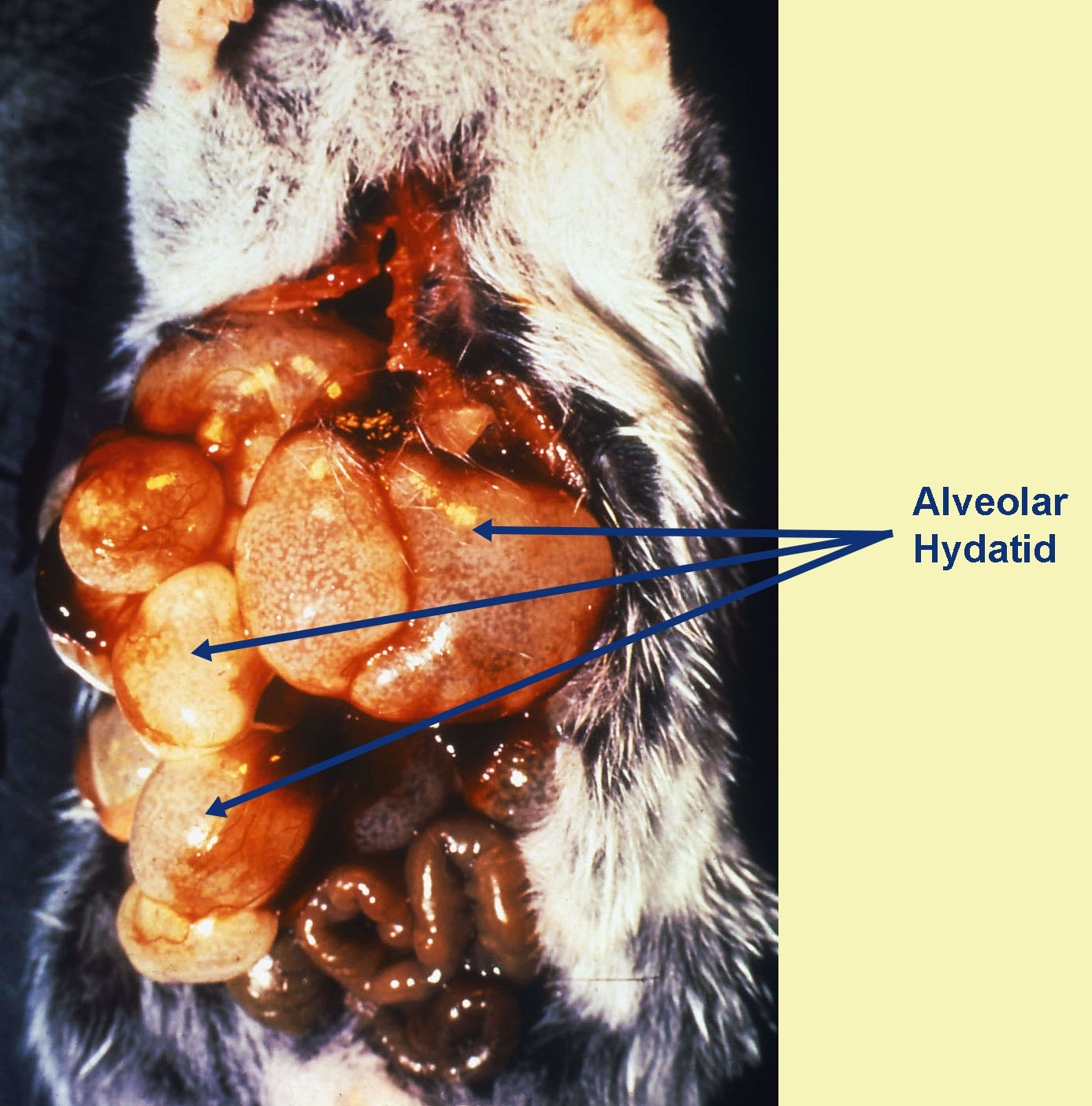

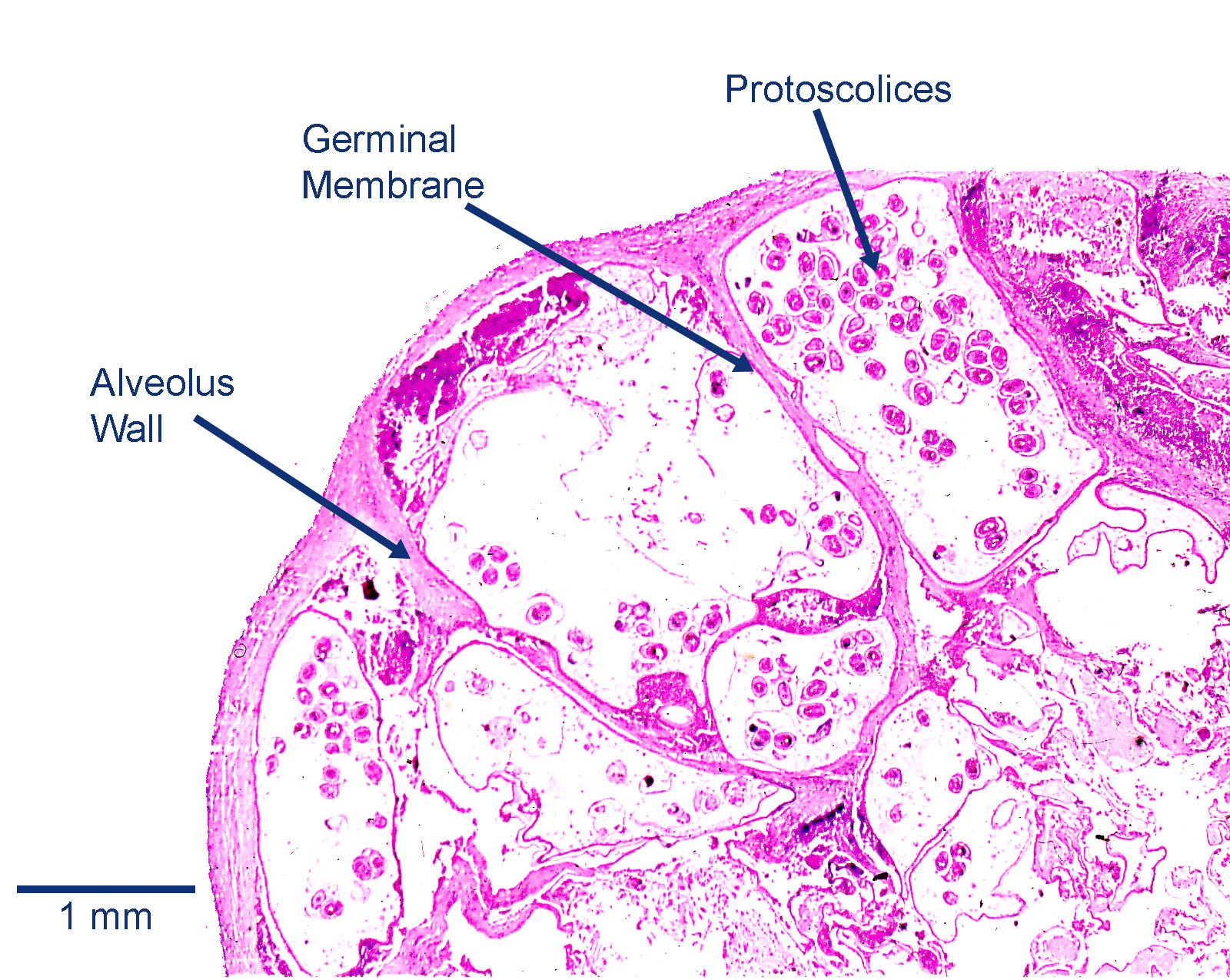

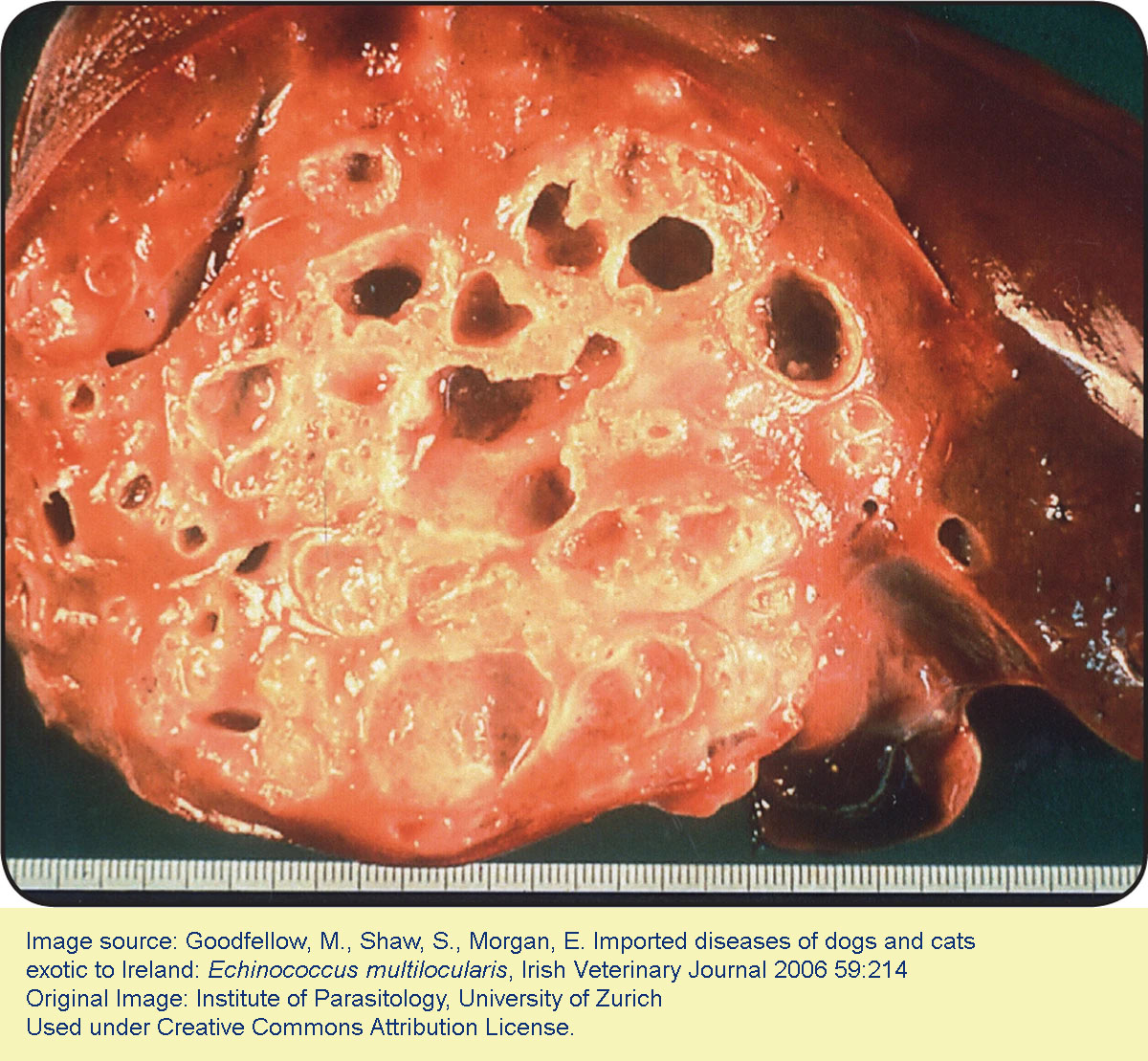

In intermediate hosts, the metacestode, or larval stage, takes the form of an alveolar hydatid cyst, usually in the liver. Typically, an alveolar hydatid in a rodent intermediate host consists of multiple, small, fluid-filled cysts (“alveoli”) lined by germinal membrane of parasite origin – from which develop the protoscolices. Each “alveolus” usually contains only a few protoscolices, but the entire cyst that develops from a single egg can contain hundreds of protoscolices. In aberrrant intermediate hosts, such as dogs, protoscolices are only present in some hosts, and the primary lesions may be associated with the metastatic behaviour of the germinal membrane alone.

Rodent IH with alveolar hydatids Liver section with Alveolar Hydatid

Host range and geographic distribution

In Canada, aAdult E. multilocularis occurs infoxes, coyotes, wolves, dogs, and (although not generally considered patent) cats as definitive hosts, and the metacestode (AE) in voles, lemmings, shrews, deer mice, and muskrats. Prevalence in coyotes ranges from 25-70% in Canada, around 30% in foxes, and 13% of wolves. The parasite appears to be rare in dogs as definitive hosts in Canada, although it has been reported most recently in Alberta. AE is increasingly being detected in dogs in North America, especially Alberta and Saskatchewan, and has been reported in British Columbia, Manitoba, and Ontario. Other aberrant intermediate hosts include primates in zoos, pigs, and horses.

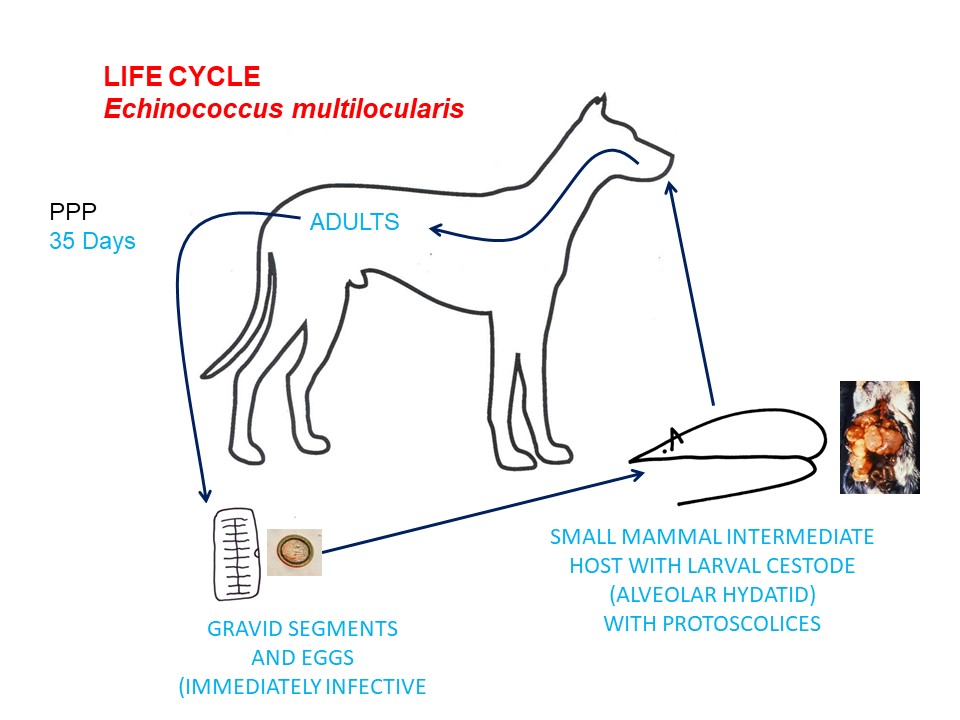

Life cycle - indirect

Adult E. multilocularis live in the small intestine of the definitive hosts and, like all cestodes of veterinary importance, are hermaphrodites. Gravid segments (or whole parasites) containing eggs pass intact in the feces or disintegrate in the GI lumen, releasing the eggs, which are also passed in the feces. If an egg is ingested by a suitable rodent intermediate host (required for completion of the life cycle) the egg hatches in the stomach. The released hexacanth larva then invades the GI wall and migrates in the bloodstream to various tissues, primarily the liver, where it develops into the infective larval stage (or metacestode)e. For E. multilocularis, this larval stage is the alveolar (multilocular) hydatid cyst, each of which can contain many protoscolices.

The life cycle continues when the alveolar hydatid in the intermediate host is eaten by a suitable definitive host. Here, the wall of the alveolar hydatid disintegrates and the protoscolices are released, each one everting to form a scolex, which attaches to the mucosa of the small intestine , produces segments, and completes their development to adults. Adult tapeworms live about 6 months, and the pre-patent period is about 1 month.

Epidemiology

Pathology and clinical signs

Diagnosis

In the carnivore definitive hosts, eggs of E. multilocularis can be detected in the feces using a centrifugation-flotation, although sensitivity is low (~30%). Fecal sedimentation methods may be better for detection of taeniid-type eggs, which are very dense and do not float well. In addition, astute owners or clinicians may be able to detect gravid segments, or even adult cestodes, in feces of heavily infected dogs, although these are very small, especially in comparison to other cestodes common in dogs. The most sensitive diagnostics for Echinococcus in the feces of dogs are coproantigen or coproPCR-based methods, the latter of which also offer the advantage of being able to distinguish among E. canadensis, E. multilocularis, and Taenia spp.

Eggs of E. multilocularis are indistinguishable microscopically from eggs of E. granulosus/canadensis and of Taenia species. In rodent intermediate hosts, diagnosis is made at post-mortem. Diagnosis of canine AE should be suspected on detection of a liver mass, especially in a young dog in a highly endemic region, via radiology or ultrasound. Definitive diagnosis relies on detection of protoscolices (in about one third of dogs) or parasite material on biopsy or cytology; PCR on tissue, aspirated abdominal fluid, or cyst contents; or serology (not available in Canada at moment)

Treatment and control

In dogs diagnosed with AE, a fecal sample should be taken and tested by coproPCR to determine if the dog was also infected with adult cestodes (true in about 20% of cases from Europe, not described in Canada to date). Then, the dog should be treated with an adult cestocide (i.e. praziquantel at 5 mg/kg); this drug has no efficacy against the metacestode stage, but will eliminate any adult cestodes while awaiting the coproPCR results. To address the AE, the dog will need to be treated daily for life (or at least 2 years) with a larval cestocide (i.e. albendazole at 10 mg/kg). Surgical debulking/resection should be performed if clinically indicated, but if caught early, medical management is often sufficient. Euthanasia should not be initiated for public health considerations, since the dog, once treated with praziquantel, poses no further risks to the owner. Many owners do elect euthanasia because of welfare considerations, or poor prognosis, especially if the infection is significantly advanced prior to diagnosis.

Public health significance

For E. multilocularis, as for E. granulosus, people are in the intermediate host position in the life cycle. If people ingest viable E. multilocularis eggs from carnivore feces, they can develop alveolar hydatids, primarily in the liver. People cannot be infected by contact with AE in the organs of rodents or dogs, but through consumption of eggs in unwashed produce, unfiltered surface water, or unwashed hands in environments heavily contaminated by infected dogs or wild canids. It is not clear how much transmission occurs directly from wild canids to people (presumably through consumption of unwashed produce or unfiltered surface water in areas contaminated by wild canid feces), or from dogs directly to people (i.e. from eggs adhering to dog fur from rolling in canid feces, or adhering to the perianal region in dogs with intestinal infections).

Human AE is often associated with clinical signs, sometimes decades after infection, and is more common in people with immunocompromise. In North America, locally acquired cases of AE in people are increasing, especially in Alberta and Saskatchewan, possibly as a result of introduced European strains of the parasite which seem to be more likely to cause canine and human AE than strains previously established in North America.

Alveolar hydatid; human liver

References

Deplazes P et al. (2017) Global distribution of alveolar and cystic echinococcosis. Advances in Parasitology 95: 315-493 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/bs.apar.2016.11.001

Houston S et al. (2021) Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of alveolar echinococcosis: an emerging infectious disease in Alberta, Canada. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene doi:10.4269/ajtmh.20-1577

Jenkins E (2017) Echinococcus spp. tapeworms in dogs and cats. Clinician's Brief 15(7):14-18. https://www.cliniciansbrief.com/article/echinococcus-spp-tapeworms-dogs-cats.

Kolapo T et al. (2021) Copro-polymerase chain reaction has higher sensitivity compared to centrifugal fecal flotation in the diagnosis of taeniid cestodes, especially Echinococcus spp, in canids. Veterinary Parasitology 292 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2021.10940

Liccioli s et al. (2012) Gastrointestinal parasites of coyotes (Canis latrans) in the metropolitan area of Calgary, Alberta, Canada. Canadian Journal of Zoology 90: 1023-1030.Peregrine AS et al. (2012) Alveolar hydatid disease (Echinococcus multilocularis) in the liver of a Canadian dog in British Columbia, a newly endemic region. Canadian Veterinary Journal 53: 870-874.

Jenkins EJ et al. (2012) Detection of European strain of Echinococcus multilocularis in North America. Emerging Infectious Diseases 18: 1010-1012.

Schurer J et al. (2016) Intestinal parasites of gray wolves (Canis lupus) in northern and western Canada. Canadian Journal of Zoology 94(9):643-650 Doi:10.1139/cjz-2016-0017

Schurer J et al. (2020). Molecular evidence for local acquisition of human alveolar echinococcosis in Saskatchewan, Canada, Journal of Infectious Diseases, jiaa473, https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiaa473

Zajac A., et al. (2020). Alveolar echinococcosis in a dog in the eastern United States. Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation, 32(5), 742–746. https://doi.org/10.1177/1040638720943842