Eutrombicula species

Trombiculid mites are free-living but their larval stages can infest a range of mammals, birds and people, causing sometimes severe skin lesions characterised by intense pruritus.

Summary

Taxonomy

Subphylum: Chelicerata

Class: Arachnida

Subclass: Acari

Order: Prostigmata

The genera Eutrombicula (in North America) and Neotrombicula (Trombicula) (in Europe) are in the same Order as Cheyletiella and Demodex, which is different from that containing Sarcoptes, Notoedres, Psoroptes, Chorioptes and Otodectes, and from that containing Dermanyssus and Ornithonyssus.

Morphology

The parasitic larvae of trombiculid mites (chiggers or harvest mites) are tiny – up to approximately 500 µm in length – and can be seen with the naked eye, in part because of their reddish colour. The larvae have six long legs and feather-like (plumose) bristles (setae) on the body and legs.

Eutrombicula sp. larva

Plumose setae

Host range and geographic distribution

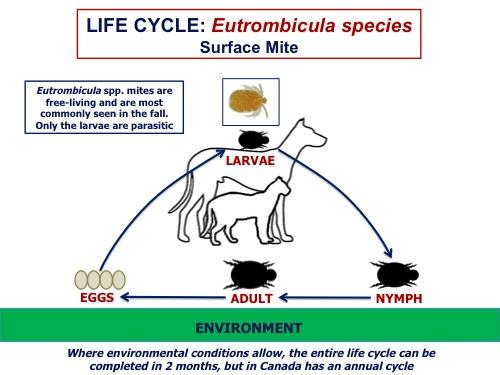

Life cycle

Epidemiology

Trombiculids are also called “harvest mites”, probably because clinical problems are seen more commonly in the fall. This may simply be because there may be higher levels of infestation in the environment at this time of year.

The reasons for the patchy spatial distribution of these mites are not understood, although it may be associated with local variations in microclimate.

Pathology and clinical signs

Diagnosis

Treatment and control

Because chiggers are essentially free-living, effective control is very difficult. Avoidance of areas known to be infested may be helpful, but detection of these usually results from a dog or cat acquiring the larval mites.

Public health significance

References

Pilsworth RC et al. (2005) Skin Disease Refresher: Trombiculidiasis. Equine Veterinary Education 17: 9-10.