Cystoisospora species

Dogs and cats around the world, especially pups and kittens, are often infected with a range of species of Cystoisospora (formerly known as Isospora).

Summary

Taxonomy

Phylum: Alveolata

Subphylum: Apicomplexa

Class: Coccidea

Order: Eimeriidae

Cystoisospora (previously Isospora) species, closely related to the genus Eimeria, are intestinal coccidians that cause coccidiosis in mammalian carnivores or omnivores. Other coccidians include the cyst forming genera of Neospora, Sarcocystis, and Toxoplasma, but the clinical syndrome of “coccidiosis” is reserved for the intestinal coccidians. Dogs and cats each have their own Cystoisospora species, which are highly host specific.

Note: Our understanding of the taxonomy of parasites is constantly evolving. The taxonomy described in wcvmlearnaboutparasites is based on Deplazes et al. eds. Parasitology in Veterinary Medicine, Wageningen Academic Publishers, 2016.

Morphology

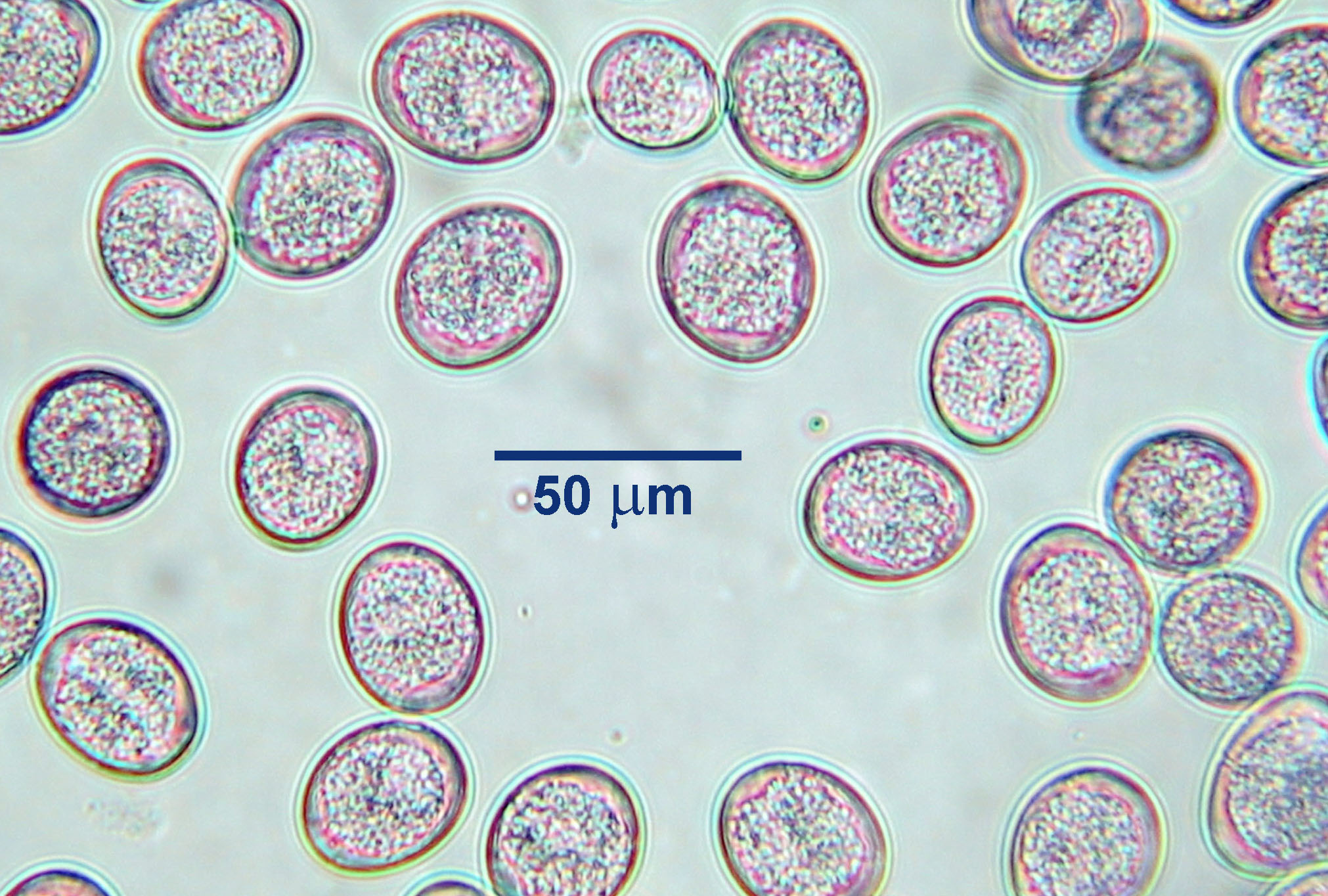

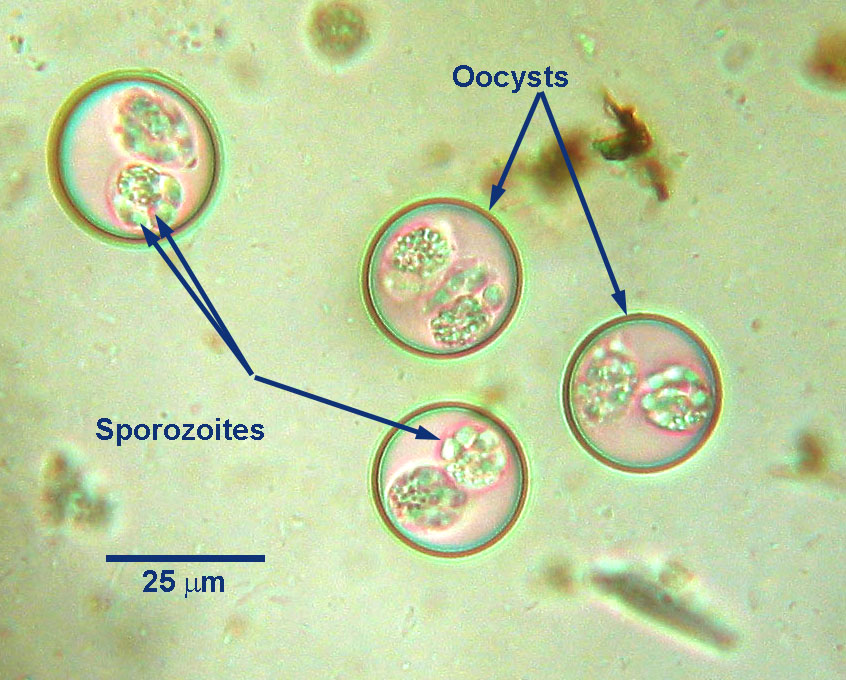

Cystoisospora species unsporulated oocysts passed in feces of dogs or cats are oval, measure up to approximately 50 by 30 µm, depending on the species, and have a thin, smooth shell. Freshly passed unsporulated oocysts contain one or two cells. A sporulated oocyst of Cystoisospora contains two sporocysts, each containing four sporozoites.

The tissue stages of Cystoisospora species visible by standard microscopy include those associated with asexual (merogony) and sexual (gametogony and fertilization) reproduction within the enterocytes of the small intestine, as well as bradyzoites in the paratenic hosts, although the last are rarely sought for diagnosis.The intestinal stages – meronts, merozoites, macrogametocytes, microgametocytes, gamonts and oocysts, are typical for the genus, and can usually be seen in histological sections.Host range and geographic distribution

Cystoisospora species occur in dogs and cats around the world, including Canada. There are many species infecting these hosts, but in North America the clinically most important are C. canis, C. ohioensis and C. burrowsi in dogs, and C. felis and C. rivolta in cats. Cystoisospora spp. were one of the most common endoparasites detected in a recent national survey of dogs and cats in shelters in Canada (Villeneuve et al., 2015). Oocysts were detected in 16% of dogs in BC and 12% of dogs in AB, SK, and MB, and in 10% of cats in BC, and 10% of cats in AB, SK, and MB. Prevalence was higher in dogs and cats less than 1 year of age.

Life cycle

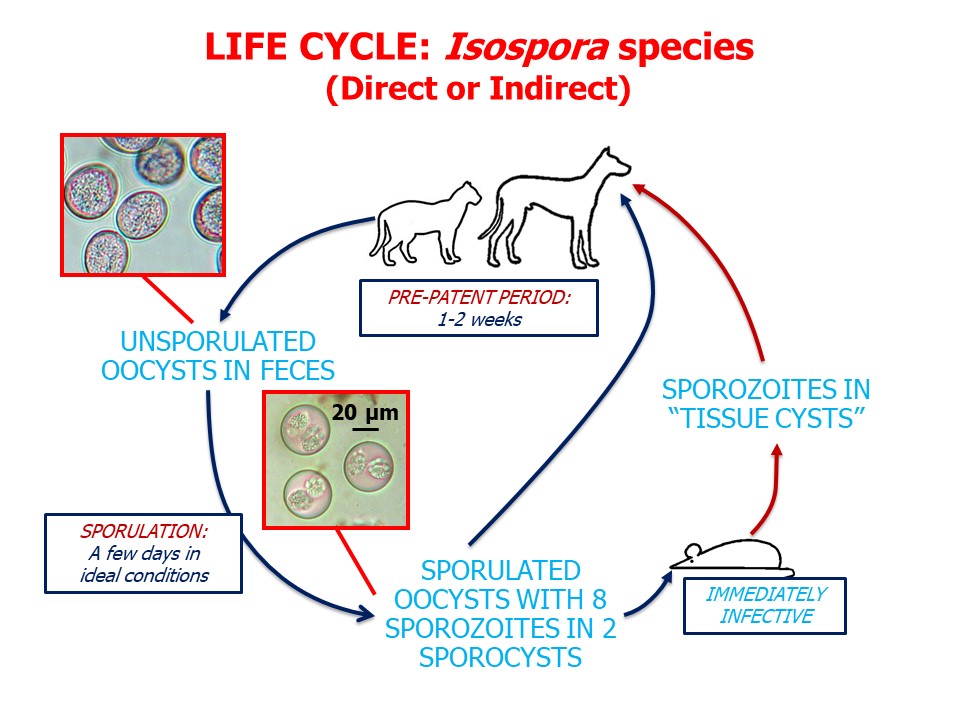

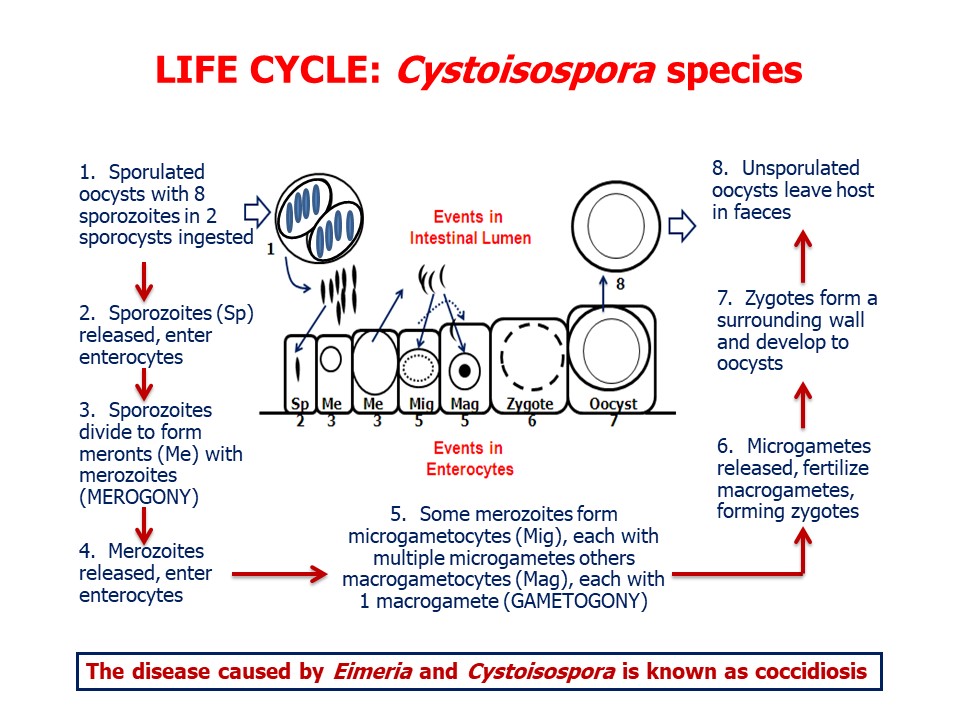

Cystoisospora species undergo asexual (merogony) and then sexual (gametogony and fertilization) reproduction in the enterocytes of the small intestine. The infective stage is the sporulated oocyst which, following ingestion by a suitable host, hatches to release eight sporozoites. These sporozoites enter enterocytes and divide rapidly to form merozoites enclosed within a meront, which can occupy most of the host cell. Depending on the species of Cystoisospora, a meront can contain up to several thousand merozoites. When merogony is complete, the infected cell bursts, releasing the meronts into the intestinal lumen, from where they penetrate new enterocytes. Depending on the species, the merogony cycle may be repeated several times, greatly increasing the number of parasites and the number of infected, and damaged, host cells.

Eventually, merozoites entering host cells do not divide to produce meronts, but instead form microgametocytes (“male”) and macrogametocytes (“female”) within the enterocytes. Each microgametocyte contains several microgametes, but each macrogametocyte contains only a single macrogamete. Next, the microgametocyte disintegrates, releasing the microgametes, which fertilize the macrogametocytes, forming gamonts which develop into unsporulated oocysts. These oocysts burst from the enterocytes into the gut lumen and are passed in feces. In the environment, over a few days under ideal conditions, the oocysts sporulate and are then infective. Infection of dogs or cats is by ingestion of sporulated oocysts.

The pre-patent period for Cystoisospora species in dogs and cats is approximately one to two weeks, and animals may shed oocysts for 2-4 weeks. The locations of the various life cycle stages within the small and large intestines varies with parasite species.

If sporulated oocysts of Cystoisospora species are ingested by paratenic hosts, usually small mammals, they hatch and the sporozoites released penetrate into the intestinal wall and encyst intracellularly as single bradyzoites. The cysts can be found in a variety of tissues and organs, particularly mesenteric lymph nodes. Ingestion of infected paratenic hosts can produce patent infections in dogs and cats.Epidemiology

Pathology and clinical signs

While the various species of Cystoisospora can be found in dogs and cats of any age, usually heavy infections are most common in pups and kittens. Even in these young animals, even the more pathogenic species (such as C. canis) may not always be associated with clinical disease. Diarrhea (watery, rarely bloody) is the most usual symptom, together with dehydration, loss of appetite and poor growth. Coccidial infection in pups and kittens is often a reflection of sub-optimal cleanliness - their environment is heavily contaminated with oocysts that have had time to become infective - and perhaps other concurrent disease. Clinical disease due to ruptured enterocytes may be observed in the pre-patent period - i.e. prior to shedding of oocysts in feces.

Diagnosis

The history and clinical signs are helpful, as is the recovery of oocysts from feces by centrifugation-flotation. To some extent, oocysts can be differentiated to species on the basis of size (C. canis and C. felis are quite large) and other morphological features, particularly if sporulated, but it is not easy. In general, the more oocysts there are, the more likely coccidia are to be the cause of clinical disease. Differential diagnoses for unsporulated oocysts in feces include Neospora caninum in dogs, Toxoplasma gondii in cats, and Hammondia spp. (in both), although Cystoisospora would be far more common, especially in young, diarrheic animals. Eimeria spp. oocysts can also be detected in feces of dogs, generally as a result of eating herbivore feces, and will often be sporulated. Additionally, some or all of the intestinal stages of the parasite can usually be seen histologically on post mortem.

Treatment and control

There are no products approved in Canada for coccidiosis in dogs or cats, but sulphonamides are commonly used extralabel. Toltrazuril is currently the treatment of choice in shelters, and in the case of an outbreak, should be administered to all exposed young dogs 3 times at 2 week intervals. The primary goal of treatment is more to reduce shedding and environmental decontamination than to treat clinical signs, as frequently the damage is already done by the time of diagnosis.

Control of coccidiosis in shelters and kennels should also include a strong focus on environmental sanitation. Oocysts are susceptible to heating over 60-70C, desiccation, and disinfectants such as cresols, phenols, and strong, fresh bleach (sodium hypochlorite) solutions given appropriate contact time (at least 10 minutes, but follow label instructions). Other methods of control include good fecal hygiene, preventing dogs and cats from hunting or scavenging paratenic hosts, and feeding only cooked or commercial diets.