Ixodes species

Ixodes spp. ticks are a genus of hard ticks found worldwide. In North America, the primary species of veterinary and public health importance are I. scapularis (in southern Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and the eastern USA) and I. pacificus (in coastal regions of western North America).

Summary

Ixodes spp. ticks are a genus of hard ticks found worldwide. In North America, the primary species of veterinary and public health importance are I. scapularis (in southern Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and the eastern USA) and I. pacificus (in coastal regions of western North America). Adult Ixodes ticks can be differentiated from other ticks in North America on the basis of their geographic origin, inornate scutum, lack of festoons, and long, parallel sided mouthparts. Ixodes spp. are 3-host ticks with the larval, nymph and adult stages occurring on different hosts, usually wildlife. It takes ~3 years to complete the life cycle. In endemic regions, nymphs and adults may be found on people and pets in spring and fall. In non-endemic regions (i.e. Alberta and Saskatchewan), adult ticks may be found on people and pets in fall, having arrived with migratory birds or through travel of people and pets to endemic regions. Ixodes scapularis (black-legged or deer tick) is the main vector for Borrelia burgdorferi, the bacteria that causes Lyme disease, and also acts as a vector for Borrelia miyamotoi, Anaplasma phagocytophilum, Ehrlichia muris, Francisella tularensis, Babesia microti, and Powassan virus. I. pacificus (western black-legged tick) is less likely to transmit pathogens, but is a competent vector for Borrelia and Anaplasma spp. There are 3 tiers to tick prevention and control in companion animals. The first is simply to avoid tick-contaminated areas, especially in the spring and autumn, and to manually check and remove ticks within 6-24 hrs. The second is to use topical repellents or oral systemic treatments to prevent tick attachment and pathogen transmission. The third, for owners greatly concerned about Lyme disease, is to consider vaccination for Lyme disease. It is rarely considered necessary to test dogs in endemic regions unless they are showing clinical signs, which is only about 5% of Lyme positive dogs. Ixodes spp. ticks are not particularly host specific and nymphs and adults will readily feed on people, to which they may transmit a range of pathogens.

Taxonomy

Phylum: Arthropoda

Class: Arachnida

Order: Metastigmata (Ixodida)

Family: Ixodidae

Ixodes spp. ticks are a genus of hard ticks found worldwide. In North America, the primary species of veterinary and public health importance are I. scapularis (in southeast North America) and I. pacificus (in coastal regions of western North America). There are also wildlife associated species that are occasionally found on people and pets, including I. kingi (the rotund tick) and I. cookei (the groundhog tick).

Morphology

Adult Ixodes spp. ticks are approximately 3 mm in length, teardrop shaped, red-brown in colour, with an inornate scutum and without festoons. Mouthparts are long and the basis capitulum is parallel sided. Males have a larger shield (scutum) than females. All stages have a characteristic anterior anal groove on the ventrum. Larva and nymphs are smaller and paler. Larvae have 6 legs. Nymphs have 8 legs and can be distinguished from adults by their size and the lack of a genital pore.

Host Range and Geographic Distribution

In Canada, I. scapularis is established in southern Manitoba, southern Ontario, southern Quebec, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia, and is continuing to expand its range as a result of changes in climate, landscape, and the interface with wildlife. I. pacificus can be found on pets and people year-round on Vancouver Island, the Gulf Islands, and coastal regions of the lower mainland. In Alberta and Saskatchewan, Ixodes spp. are not yet established, but can be found on pets and people, frequently in fall, having been brought into the province as nymphs on migratory birds in the spring (adventitious ticks). Ixodes spp. ticks also may be found on pets and people that have travelled to endemic regions. Due to grooming, cats are generally less likely to allow ticks to attach and feed than dogs, but ticks are not infrequently found on outdoor cats, including Ixodes spp.

Life Cycle

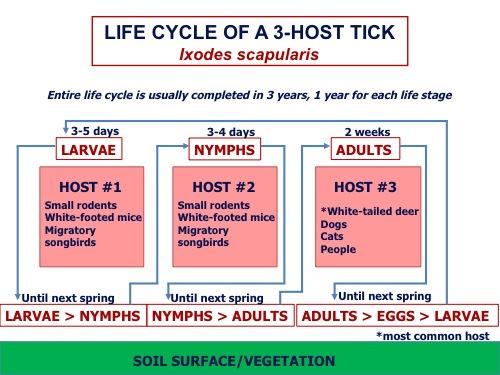

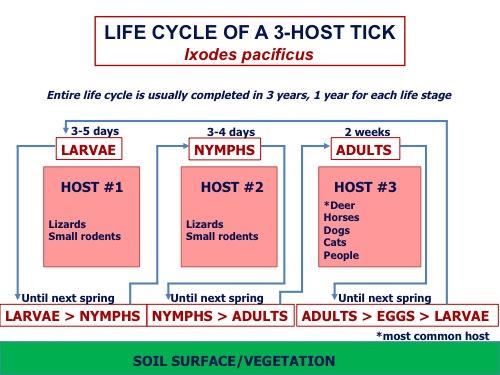

Ixodes spp. are 3-host ticks with the larval, nymph and adult stages occurring on different hosts. It takes ~3 years to complete the life cycle, one year for each of the developmental stages. The larva and nymphs usually feed on small rodents, birds or lizards, whereas adult ticks feed on larger mammals.

Larvae attach to a host and feed for 3-5 days then return to the environment to overwinter and develop into nymphs. The following year the nymph attaches to a new host and feeds for 3-4 days before dropping back into the environment to overwinter and develop into an adult. The adults become active in the fall and can remain active through the winter if there are days where the temperatures are above freezing. Mating usually takes place on the host, after which the female feeds for about 14 days, then drops off the host and lays eggs in sheltered locations before dying. Adult females feed only once after mating but adult males feed and mate repeatedly. The following year the eggs hatch in the environment and the larvae quest for a new host.

Epidemiology

Ixodes scapularis requires high humidity and deep leaf litter to survive and can only feed when the temperature and humidity are appropriate, usually in the spring and autumn. The larva and nymphs usually feed on small rodents, predominantly white-footed mice, and many species of migratory songbirds. Adult I. scapularis feed on larger mammals, predominantly white-tailed deer, but will feed on many other species including dogs, cats and people. In endemic regions, nymphs are usually on pets and people in late spring and early summer, while adults are generally found on pets and people in spring and fall. However, adults can be active overwinter on days where temperatures are greater than 4 C.

Ixodes pacificus is found in forests, northern coastal scrub, high brush and open grasslands in coastal BC. Larva and nymph stages feed mostly on small rodents and lizards. Adult ticks feed on larger mammals including deer, horses, dogs and cats. Adult I. pacificus can be found on pets and people from early winter to late spring.

Pathology and Clinical Signs

In general, tick bites can result in localized dermatitis and bacterial infection. More concerningly, Ixodes spp. ticks also transmit a range of systemic pathogens, generally requiring at least 6-24 hrs of attachment on their host.

Ixodes scapularis is the main vector for Borrelia burgdorferi, the bacteria that causes Lyme disease, as well as Borrelia miyamotoi, Anaplasma phagocytophilum, Ehrlichia muris, Francisella tularensis, Babesia microti, and Powassan virus .

xodes pacificus is a vector for Anaplasma phagocytophilum, Babesia microti,, and Borrelia spp. Ixodes pacificus is thought to be a relatively ineffective vector for Lyme disease, since it often feeds on lizards which are not competent reservoirs for the infection. Ixodes pacificus has been associated with a rabbit with tick paralysis, but this does not appear to be reported in pets or people.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of Ixodes spp. infection is made by discovery and identification of the ticks on the animal. Nymphs are quite small, rarely detected by owners, and more difficult to identify. Adult Ixodes spp. ticks are easily distinguished by veterinary personnel from other tick species based on their lack of ornate scutum, lack of festoons, and long, parallel sided mouthparts. Owners in most of Canada can also submit digital pictures of ticks to etick (https://www.etick.ca) to get ticks identified to genus level within 24-48 hrs.

If owners are concerned about transmission of Lyme disease or anaplasmosis following the bite of an Ixodes spp. tick, dogs can be tested at least 6-8 weeks after the bite using a serological test for antibodies. It is rarely considered necessary to test dogs in endemic regions unless they are showing clinical signs, which is only about 5% of Lyme positive dogs. Likewise, ticks themselves can be tested for pathogens by PCR, although the presence of DNA of a pathogen in a tick, especially one that has fed on a host, does not mean that the tick is actually infected and competent to transmit that pathogen.

Treatment and Control

There are 3 tiers to tick prevention and control in companion animals. The first is simply to avoid tick-contaminated areas, especially in the spring and autumn. The second is to manually check and remove ticks within 6-24 hrs of being active in tick habitat. Prompt removal of ticks prevents pathogen transmission and, for some species, tick paralysis. The third tier is to use topical repellents or systemic treatments (often also used for flea control) to prevent ticks from attaching and/or transmitting pathogens. Veterinary-prescribed topical spot-ons and collars (permethrin, imidacloprid) are effective but these insecticides may have secondary toxicity effects, especially for cats in the household. Older topical macrocyclic lactones (i.e. selamectin) have some efficacy against ticks, but the preferred systemic treatments are the oral isoxazolines, administered monthly (or every 3 months) during the tick season. In central BC, Alberta, and Saskatchewan, this is April to June, although owners should remain alert for adventitious Ixodes ticks in fall. In coastal BC, flea and tick control is often needed year round. In southern Manitoba and eastern Canada, tick prevention is primarily needed in spring (Apr-June) and fall (Sept-Nov), although in warmer regions, adult Ixodes may be active overwinter as well. Finally, owners who are particularly concerned about Lyme disease may wish to have their dog vaccinated. However, this will only protect their dog against Lyme disease, and therefore tick control is also needed to prevent transmission of other pathogens.

Public Health Significance

Ixodes spp. ticks are not particularly host specific and nymphs and adults will readily feed on people. People generally acquire ticks from the environment, the same way that pets do, not directly from pets. Nymphs are particularly hard to see, and may be one of the more important sources of human exposure to Lyme disease in endemic regions. People can reduce risk of exposure to ticks by reducing time spent in tick habitat during peak tick activity periods, wearing long sleeved shirts and pants tucked into socks, using repellents or repellent impregnated clothing, and doing tick checks on themselves, children, and pets within 6-24 hrs after being active in tick habitat.