Lice Dogs and Cats: chewing (Mallophaga), and sucking (Anoplura)

Lice occur on dogs and cats around the world. In Canada dogs are hosts to both sucking and chewing lice (Linognathus setosus and Trichodectes canis, respectively), and cats only to chewing lice ( Felicola subrostratus), which are most commonly seen on farm cats.

Summary

Lice occur on dogs and cats around the world. In Canada, dogs are hosts to both sucking and chewing lice (Linognathus setosus and Trichodectes canis, respectively), and cats only to chewing lice ( Felicola subrostratus) - which are most commonly seen on farm cats. The life cycle of lice occurs entirely on the host and transmission is usually by direct contact between hosts. Life cycle stages can, however, survive for short periods in the environment, especially chewing lice. Clinically, lice cause irritation and hair loss, frequently on the dorsum, and attempts by the host to relieve this can cause additional skin lesions. Heavy burdens of sucking lice in dogs can lead to significant blood loss. In western Canada, lice infestations, especially in young pups, may be increasing. Chewing and sucking lice of pets are easily distinguished from each other by the relative size of the heads. Control of lice on pets is best accomplished through treatment of all in-contact animals of the same species, cleaning of bedding, apparel, and grooming tools, and addressing underlying management and health issues. Older topical insecticide treatments may still be used (on-label only) for dogs, but may require subsequent treatment in 1-2 weeks as nits are naturally resistant. Newer flea and tick products (macrocyclic lactones, isoxazolines) have high efficacy against lice, especially sucking lice. Lice are relatively host specific and so zoonotic transmission is unlikely. Very rarely human lice, particularly the pubic louse (Pthirus pubis), can transiently be found on dogs and cats.

Taxonomy

Phylum: Arthropoda

Subphylum: MandibulataClass: Insecta

Order: Phthiraptera

Sub-order: Mallophaga (Chewing Lice), now Ischnocera

Sub-order: Anoplura (Sucking Lice)

In Canada, the lice infecting dogs are Trichodectes canis (chewing) and Linognathus setosus (sucking). Cats are usually hosts to only Felicola subrostratus (chewing). Occasionally, dogs and cats are transiently infested with human lice. However, lice are generally host-specific.

Morphology

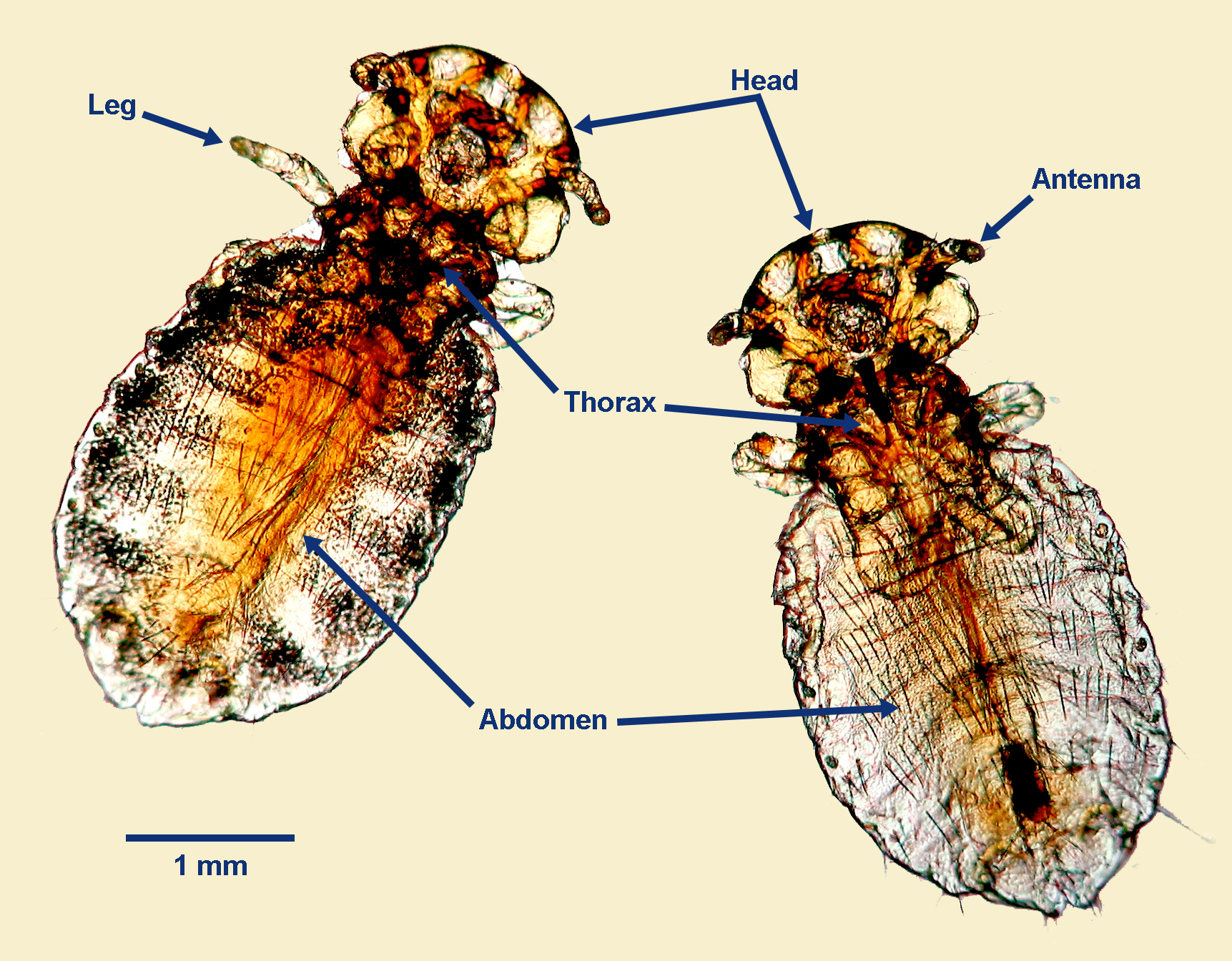

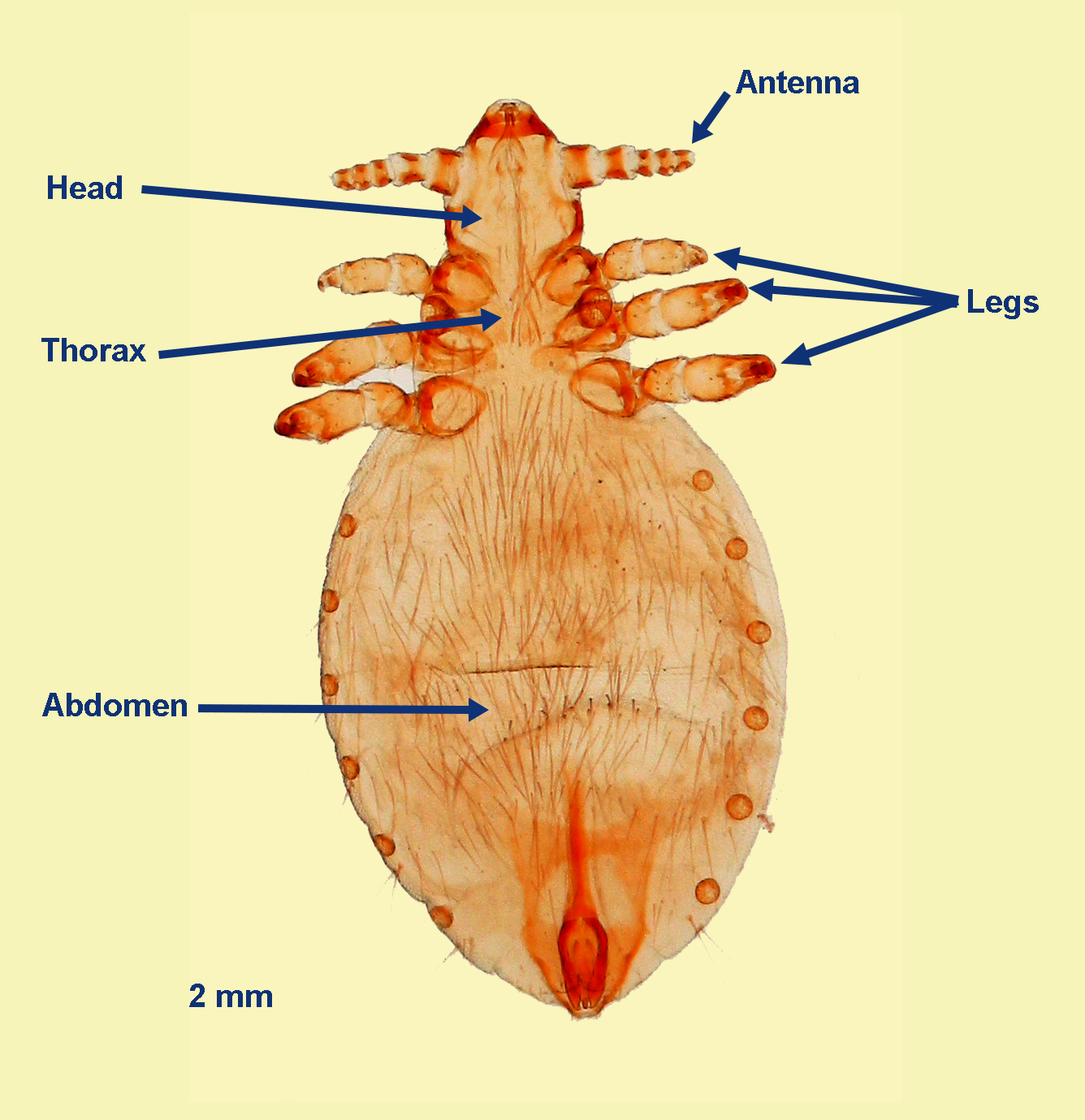

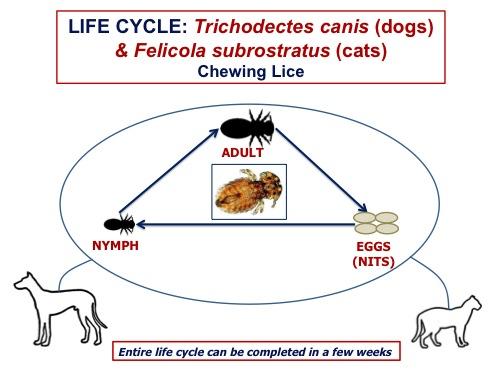

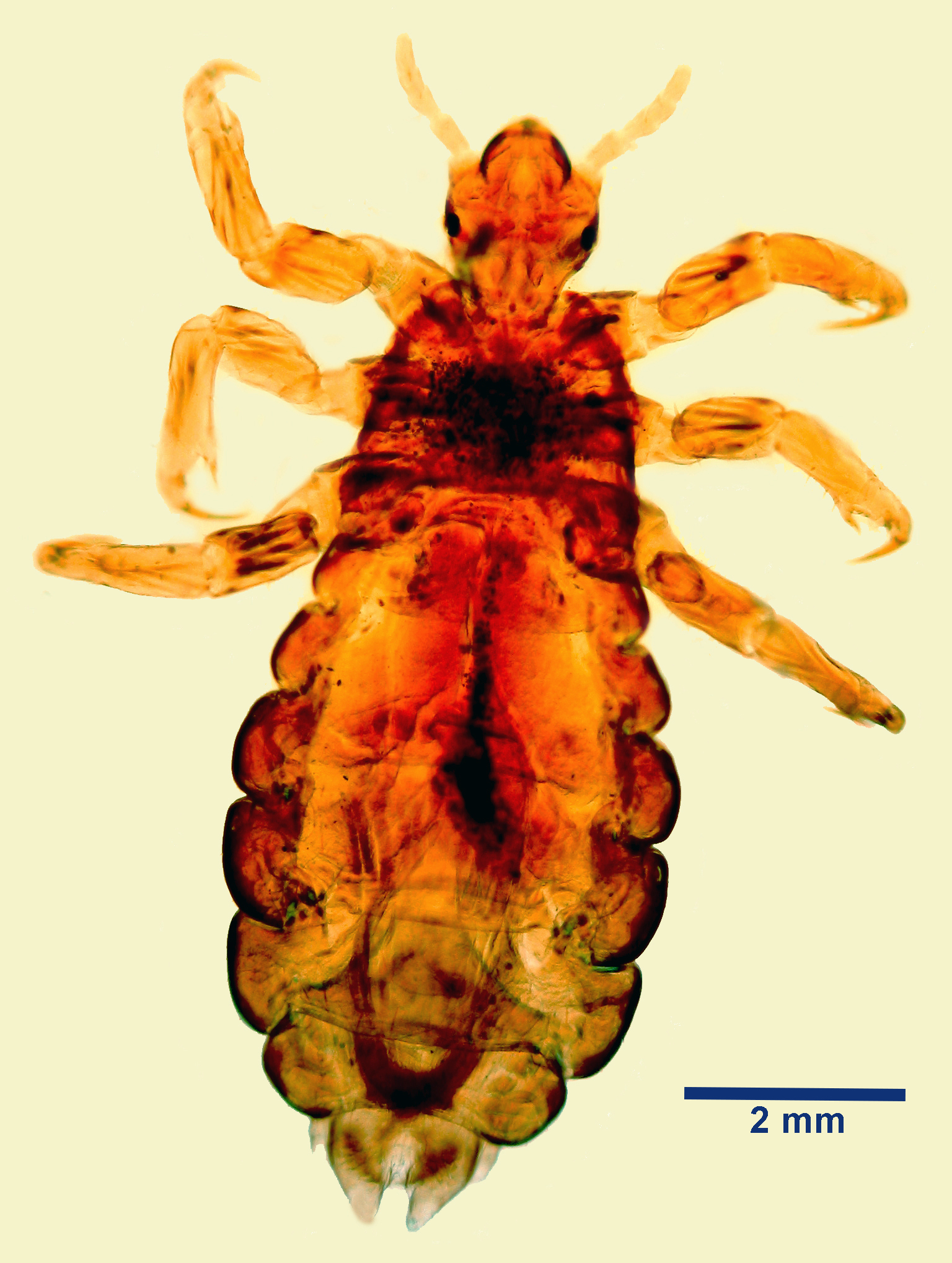

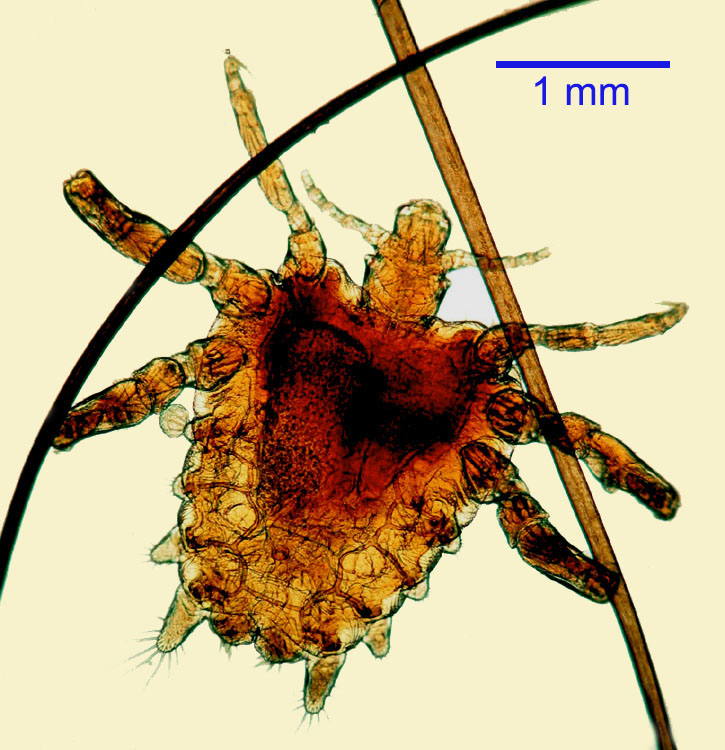

Adult chewing and sucking lice are a few mm in length, dorso-ventrally flattened, with six legs and without wings. In sucking lice, the head viewed from above is usually pointed and narrower than the thorax; in chewing lice the head is blunted, convex and wider than the thorax. For Linognathus, the most anterior set of legs is shorter than the other 2 pairs.

Host range and geographic distribution

Chewing and sucking lice occur on dogs, and to a lesser extent on cats, around the world, and may be becoming more common on dogs and wild canids in western Canada. Trichodectes canis is the primary chewing louse of dogs; in cats it is Felicola subrostratus. The latter is uncommon in western Canada, where it occurs most often on farm cats. The common sucking louse of dogs is Linognathus setosus. Lice are more or less host-specific, although small numbers of lice are occasionally found on atypical hosts, for example human lice on dogs and cats.

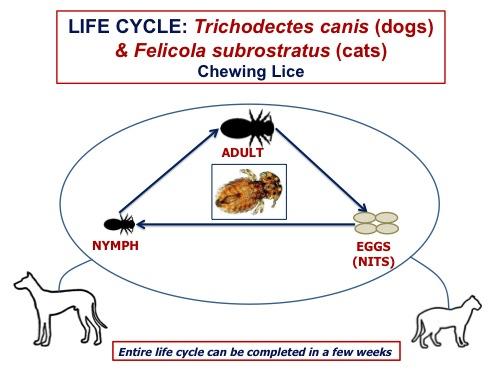

Life cycle

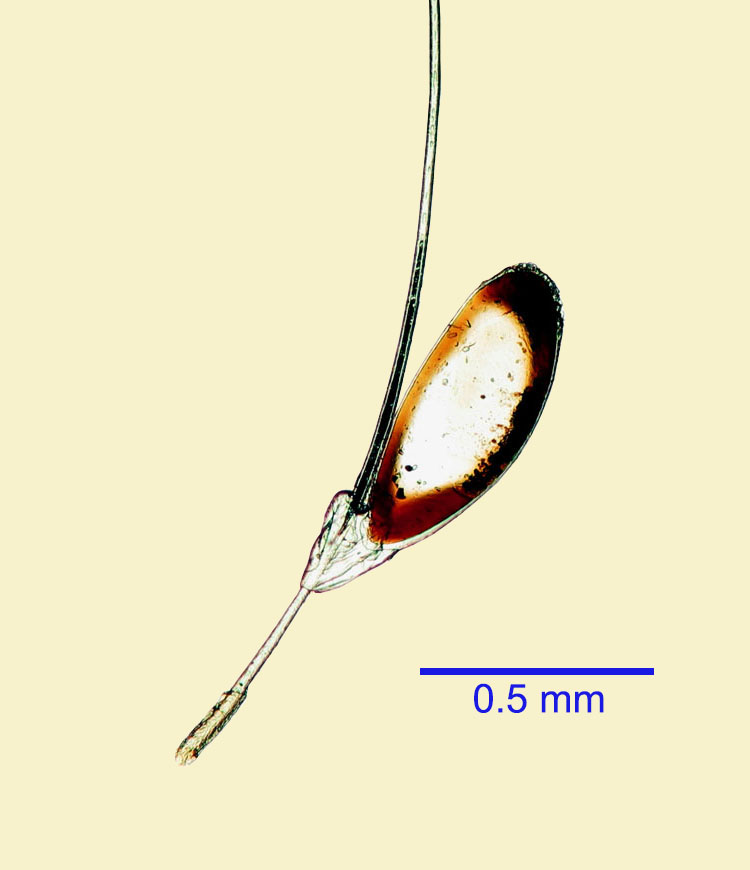

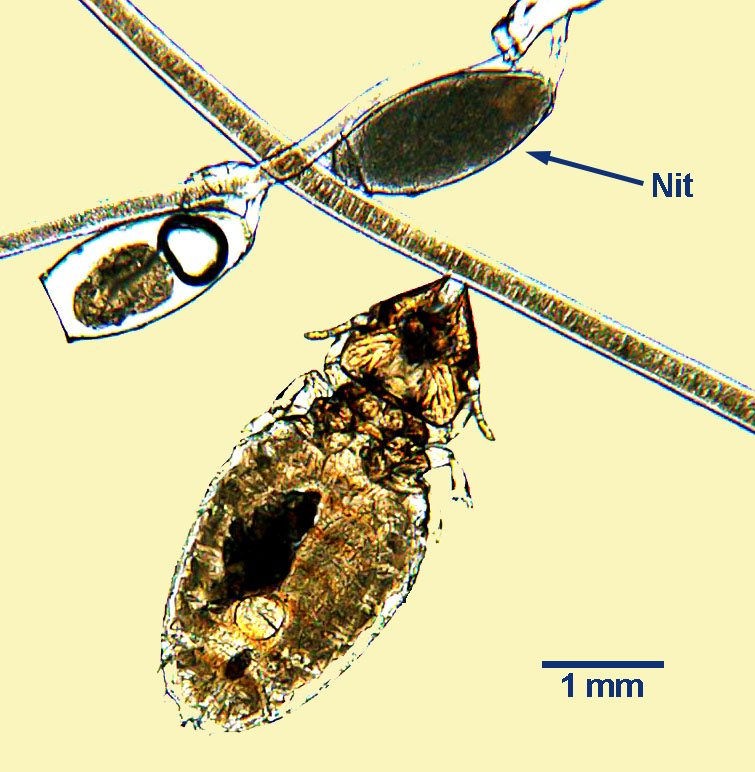

The entire life cycles of chewing and sucking lice occur on the host. Sucking lice survive off the host for a maximum of a few days, while chewing lice may survive for several weeks in the environment. Adult female lice lay eggs (nits) attached to hairs. A nymph stage develops in each egg, which hatches and the nymph released undergoes two moults to become an adult (incomplete metamorphosis, no pupae). The whole life cycle can be completed in a few weeks.

Epidemiology

Chewing and sucking lice are more or less host specific. Louse infestation spreads by direct contact between infested hosts or through inanimate fomites, for example bedding and grooming equipment. Any life cycle stage can transmit lice among animals. Some animals seem to be carriers for lice, without showing clinical signs. Generally, the most clinically affected animals tend to be young, stressed animals in high density conditions, or older animals with concomitant disease or neglect.

Pathology and clinical signs

Diagnosis

The best method is visualization of adult lice and/or nits in the haircoat, perhaps using a comb, confirmed by microscopic examination. Lice can also be recovered using tape and mounted on slides for identification, or large clumps of fur containing nits and adults can be digested (in KOH) to facilitate recovery and visualization. Chewing and sucking lice of pets are easily distinguished from each other by the relative size of the heads, and from human lice by the absence of “eyes”, and their body shape.

Treatment and control

Public health significance

While lice are more or less host-specific, they will sometimes “camp” on an atypical host. The human pubic louse,Pthirus pubis (known in French as papillons d’amour or butterflies of love) is sometimes recovered from dogs and cats. It is important to communicate to clients that pets are not a reservoir for, or source of, human infestations with these lice.

Pediculus capitis (human head louse) adult. Phthirus pubis (human pubic louse): Adult.

References

Arther RG (2009) Mites and lice: biology and control. Veterinary Clinics of North America Small Animal Practice 39: 1159-1171.

Kohler-Aanesen, Heike & Saari, Seppo & Armstrong, Rob & Péré, Karine & Taenzler, Janina & Zschiesche, Eva & Anja, Renninger. (2017). Efficacy of fluralaner (Bravecto™ chewable tablets) for the treatment of naturally acquired Linognathus setosus infestations on dogs. Parasites & Vectors. 10. 10.1186/s13071-017-2344-9.