Mesocestoides species

Adults of the cestode genus Mesocestoides occur in dogs, cats, free-ranging carnivores, and very rarely people, in many parts of the world.

Summary

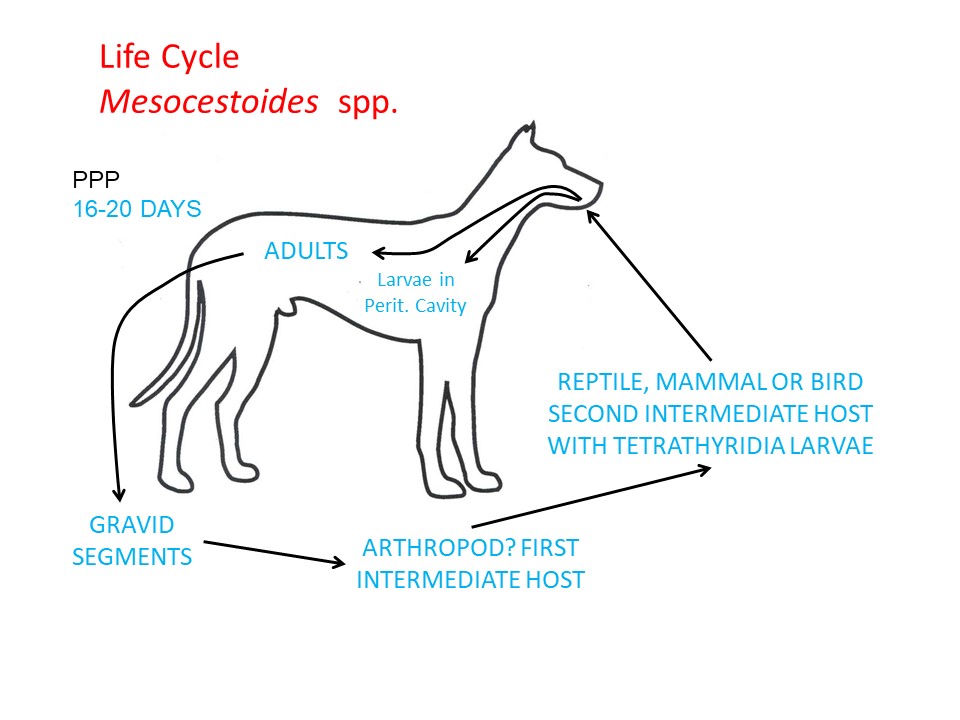

Adult cestodes of the genus Mesocestoides occur in dogs, cats, free-ranging carnivores, and very rarely people, in many parts of the world. The parasite is rarely diagnosed in Canada. It is an atypical cyclophyllid, with morphology and life cycle characteristics more commonly seen in pseudophyllid cestodes. The life cycle of Mesocestoides is not completely known. The first intermediate host is likely some kind of arthropod. Second intermediate hosts include a wide range of vertebrates, including mammals, birds, and reptiles, in which the metacestode larval stage is known as the tetrathyridium s. While adult Mesocestoides are rarely associated with significant clinical effects, sometimes in dogs the tetrathyridia do not develop to adults but instead invade the peritoneal cavity, where they can cause a serious parasitic peritonitis. This condition has been seen in dogs in Vancouver that wintered in California, where Mesocestoides is relatively common.

Taxonomy

Phylum: Platyhelminthes

Class: Cestoda

Order: Cyclophyllida

Family: Mesocestoididae

The Family Mesocestoididae is part of the Order Cyclophyllida, but segments of Mestocestoides have a ventral genital pore (typical of pseudophyllids), and the parasite has a life cycle unlike other cyclophyllid tapeworms that are important in animal or human health. M. variabilis is the species most commonly detected in North America, whereas M. litteratus and M. lineatus are more commonly reported in Europe and Asia. M. vogae (previously M. corti) and M. lineatus are implicated in larval peritonitis.

Note: Our understanding of the taxonomy ofparasites is constantly evolving. The taxonomy described in wcvmlearnaboutparasites is based on Deplazes et al. eds. Parasitology in Veterinary Medicine, Wageningen Academic Publishers, 2016 .

Morphology

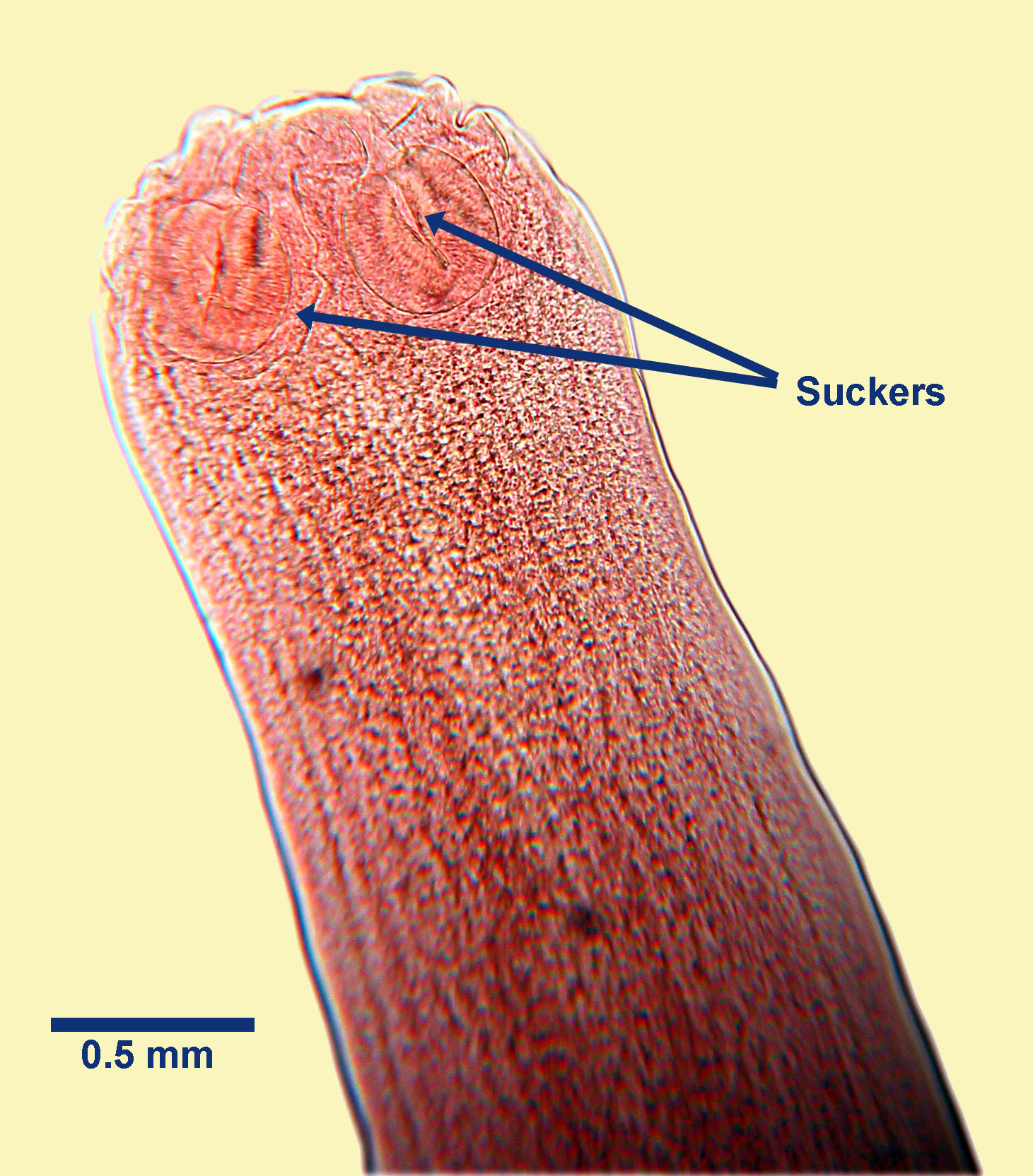

Adult Mesocestoides species are large (up to 20 cm in length, or more) and have an anterior scolex (attachment or holdfast organ), behind which is the ribbon-shaped, segmented body. Typically, anterior immature segments are smaller than mature and gravid segments towards the posterior. The scolex has no distinct rostellum and no hooks (an unarmed scolex). Behind the tip of the scolex are four elongate muscular suckers. Each mature segment of Mesocestoides contains a single set of reproductive organs, and each segment has a ventral genital pore (this is usually lateral in cyclophyllids) at about the mid-point of the segment. These pores are difficult or impossible to see, even with a microscope.

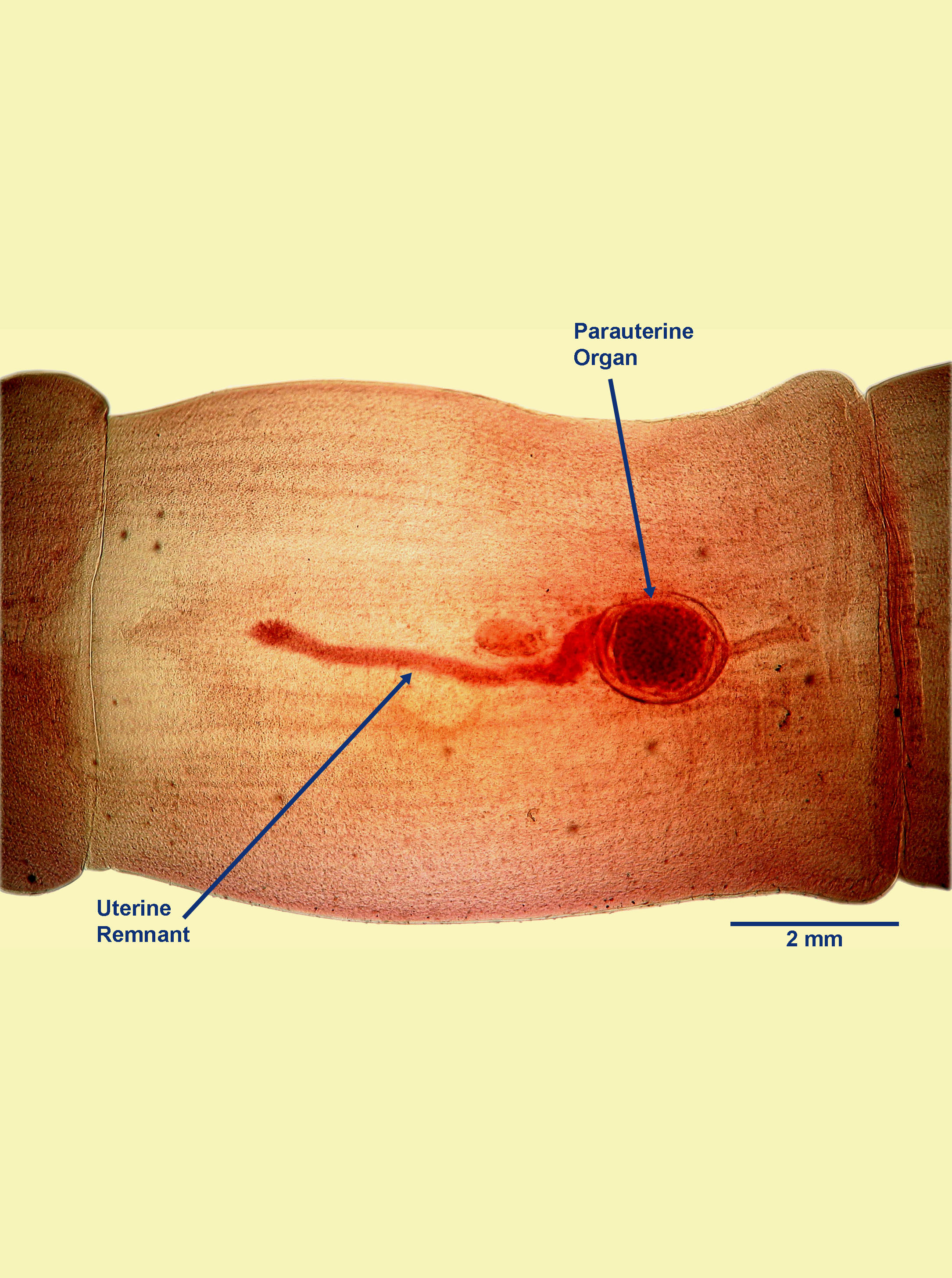

In gravid segments, the eggs of Mesocestoides species are contained in a distinctive parauterine organ (which looks something like a miniscule soccer ball) located centrally towards the posterior end of the segment, with uterine remnants anteriorly and posteriorly. The individual eggs are not visible.

Host range and geographic distribution

Adult Mesocestoides species occur in dogs and cats, free-ranging carnivores, and very rarely in people, generally in warmer areas of the world. Mesocestoides infection (adults, and/or aberrant larvae) is seen rarely in dogs in Canada. Adult cestodes are occasionally found in wild canids and mustelids in Canada, generally in coastal regions.

Life cycle - indirect

Adult Mesocestoides species live in the small intestine of the definitive hosts and, like all cestodes of veterinary importance, are hermaphrodites, reproducing sexually. Gravid segments, each of which contains a parauterine organ, drop off and pass intact in the feces or disintegrate in the GI lumen, releasing the parauterine organs, which are also passed in the feces. Unusually, adult Mesocestoides are also able to increase their numbers in the intestine of the definitive host by budding new individuals from the scolex region (asexual reproduction inside the definite host). This feature of the life cycle is not thought to be of any direct significance to the definitive host.

An arthropod first intermediate host is believed to ingest the segments, and/or the parauterine organs, and/or eggs, and to support development of the next larval stage, which has not been characterised. The life cycle is believed to continue when the infected arthropod is ingested by a suitable small reptile, mammal or bird second intermediate host, in which a tetrathyridium - the larval stage infective for the definitive host – develops. Tetrathyridia reproduce asexually in the body cavity of the second intermediate host. The life cycle is completed when an infected second intermediate host is ingested by a dog or cat, and the tetrathyridia are released and complete development to adults in the GI lumen. In some dogs the ingested tetrathyridia do not develop to adults in the GI lumen, but instead penetrate through the intestinal wall and enter the peritoneal cavity, increase their number by budding, and can cause a parasitic peritonitis. This can be clinically significant, and is sometimes fatal. A few cases of this condition have been seen in western Canada in dogs that have wintered in California, where the parasite is relatively common.

Epidemiology

Because the life cycle of Mesocestoides is incompletely known, describing the epidemiology is difficult. It seems possible that dogs and cats are usually only incidentally infected in transmission cycles in which wildlife are the primary definitive hosts.

Pathology and clinical signs

Generally the adults in dogs and cats are asymptomatic. In some dogs, however, the tetrathyridia do not develop to adults in the intestine, but instead invade the peritoneal cavity, causing a parasitic peritonitis. This can cause severe clinical signs, including abdominal distension, anorexia, vomiting, and even death. This condition has been seen in two dogs in Vancouver that wintered in California, where Mesocestoides is relatively common.

Diagnosis

Single or multiple segments of Mesocestoides, or more rarely whole adults, can be detected in feces. They are usually easily identifiable because of the prominent parauterine organ in each segment. Eggs are not usually seen in feces. Diagnosis of the parasitic peritonitis is usually initially by ultrasound and definitively following paracentesis and microscopic or molecular identification of the recovered tetrathyridia.

Treatment and control

Adult Mesocestoides tapeworms are susceptible to some of the drugs approved in Canada for tapeworm treatment in dogs and cats. Oral praziquantel is the drug of choice for the adult tapeworms (the label claim in Canada is for M. corti). Subcutaneous praziquantel given two weeks apart is more effective against larval peritonitis than oral or intra-peritoneal fenbendazole. Additional treatment of the parasitic peritonitis may involve draining and flushing the peritoneal cavity.

Effective control of Mesocestoides means preventing dogs and cats from eating the vertebrate intermediate hosts, and in many cases this is a significant challenge.

Public health significance

Although Mesocestoides can infect people (as definitive hosts) following ingestion of infected second intermediate hosts, it is a very rare occurrence and has not been reported in Canada. There are a few reports of human infection from the United States and Asia.

References

Fuentes MV et al. (2003) A new case report of human Mesocestoides infection in the United States. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 68: 566-567.