Nanophyetus salmincola

Adults of the trematode Nanophyetus salmincola live in the small intestine of domestic dogs and free-ranging fish-eating mammals in northwestern North America and eastern Russia.

Summary

Taxonomy

Phylum: Platyhelminthes

Subphylum: Trematoda

Class: Digenea

Order: Plagiorchiida

Family: Troglotrematidae

Nanophyetus is within the same Order as the ruminant liver fluke, Dicrocoelium dendriticum, and the lung fluke, Paragonimus kellicotti, which infects a wide range of mammals. In common with other digenean flukes, Nanophyetus has an indirect life cycle involving a molluscan intermediate host.

Note: Our understanding of the taxonomy of parasites is constantly evolving. The taxonomy described in wcvmlearnaboutparasites is based on Deplazes et al. eds. Parasitology in Veterinary Medicine, Wageningen Academic Publishers, 2016.

Morphology

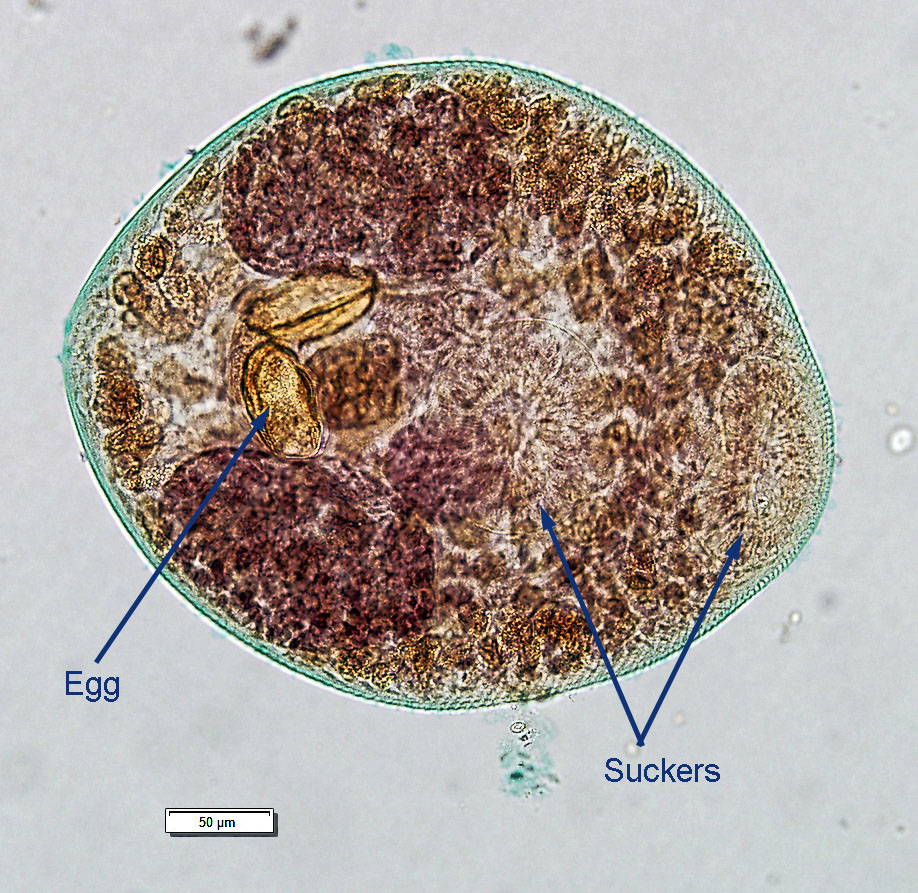

Adult N. salmincola are very small, measuring up to 3 mm in length. On microscopic examination of fixed, stained specimens, the one or two deep brown eggs in the uterus are the most obvious features, although it is sometimes possible to see the oral and perhaps the mid-body ventral suckers.

Nanophyetes salmincola: Stained and mounted adult containing eggs

The eggs of N. salmincola are typical for a trematode. They measure approximately 50 to 80µm by 30 to 55µm, have a thin smooth shell and an operculum, and are yellow-brown in colour. Little internal detail is visible in the eggs recovered from faecal flotations.

Nanophyetes salmoncola: egg

Host range and geographic distribution

Nanophyetus salmincola occurs in fish-eating mammals, including dogs, cats, wild canids, wild mustelids, bears, and people, in north-western North America and in Siberia. In Canada, the parasite has been reported in dogs on Vancouver Island.

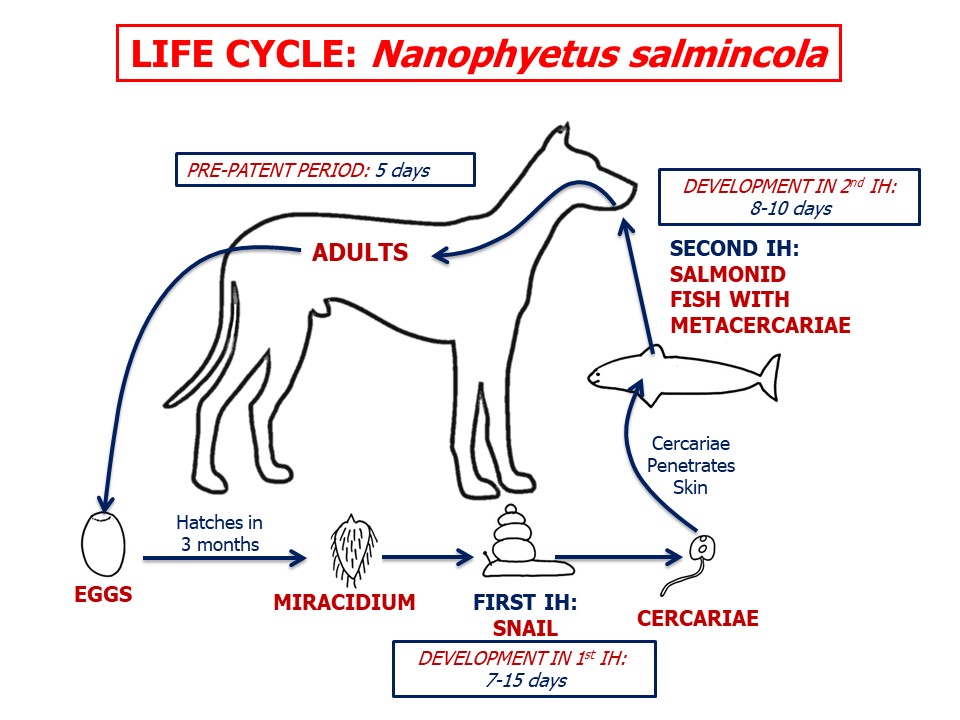

Life cycle - indirect

Adult N. salmincola are located in the small intestine of the definitive host and, like most other flukes, are hermaphrodite and reproduce sexually. Eggs are shed in the feces of the definitive host. In an aquatic environment, a miracidium (the first larval stage) develops within each egg and, following opening of the operculum, is released into the water.

For the life cycle to continue, the miracidium must penetrate the skin of a suitable snail first intermediate host, in which a sporocyst develops. Several rediae develop within each sporocyst, which then burst, releasing the rediae into the tissues of the snail. Subsequently, several cercariae develop within each redia, which bursts. The cercariae leave the snail and must then penetrate the skin of a fish second intermediate host and develop to metacercariae (infective larval stage), primarily in the skeletal muscles. The fish involved in the life cycle of Nanophyetus are the salmonids (salmon and its relatives).

Nanophyetus, like other flukes, can increase its numbers in both the definitive and intermediate hosts. Infection of the carnivore definitive host follows ingestion of an infected fish. Following ingestion by the definitive host, the metacercariae complete development to adult flukes in the GI lumen.

Epidemiology

Like the other flukes of dogs, N. salmincola depends for persistence on the presence of infected definitive hosts, together with suitable snail and fish intermediate hosts. Also like other flukes, Nanophyetus is not dependent solely on sexual reproduction in the definitive host to increase its numbers; N. salmincola also reproduces asexually in the snail first intermediate host. Additionally, although the miracidia that hatch from the eggs are relatively fragile and short-lived, the metacercariae in the fish can survive and remain infective for the lifespan of the fish.

Pathology and clinical signs

Adult N. salmincola in their definitive hosts are essentially non-pathogenic, although there have been reports of clinical GI signs in very heavily infected dogs. Nanophyetus salmincola is potentially very significant, however, because the flukes can transmit Neorickettsia helminthoeca, intracellular endosymbiotic rickettsial bacteria that cause of Salmon Poisoning Disease (SPD) in dogs, other canids, and rarely in other piscivorous mammals. SPD is a severe and commonly fatal hemorrhagic gastro-enteritis. The disease can occur wherever N. salmincola is present (Pacific northwest of the USA), and has been reported in dogs on southern Vancouver Island. Neorickettsia helminthoeca is transmitted transovarially from one generation of flukes to the next.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of the fluke infection per se is rarely attempted, unless SPD is suspected. Eggs of N. salmincola can be detected in fecal centrifugation-flotations, and can be distinguished from those of other flukes. While sugar flotation has a good sensitivity, other flotation solutions may not work as well, and sedimentation methods may also be useful for dense trematode eggs.

For SPD, diagnosis is based on history (ingestion of raw, unfrozen salmon within days of the appearance of clinical signs), the clinical signs, and the detection of Nanophyetus eggs in feces. In the cases of SPD on Vancouver Island, Neorickettsia organisms were seen in Giemsa-stained lymph node aspirates.

Treatment and control

There are no drugs approved in Canada for Nanophyetus spp. in dogs. Praziquantel has some effect on adult N. salmincola. This is an extralabel use. Treatment of SPD with appropriate antibiotics (such as doxycycline) is the highest priority when the disease is suspected.

The most effective means to control N. salmincola infection in dogs, and Salmon Poisoning Disease, is not to feed raw or inadequately prepared fish intermediate hosts. Fish should be cooked or frozen solid to inactivate metacercaria prior to feeding to dogs. Keeping dogs from defecating near water bodies prevents the eggs in the feces from reaching an aquatic environment containing the snail intermediate hosts .

Public health significance

Human infection with the fluke (N. salmincola) has been reported occasionally in people in the US, but not in Canada. In at least one human case, there was no history of fish consumption, and it was believed that the infection was acquired from handling infected fish. Salmon poisoning has apparently been reported very rarely in people, but not in Canada.

References

Booth AJ et al. (1984) Salmon poisoning disease in dogs on southern Vancouver Island. Canadian Veterinary Journal 25: 2-6.