Oslerus (Filaroides) osleri

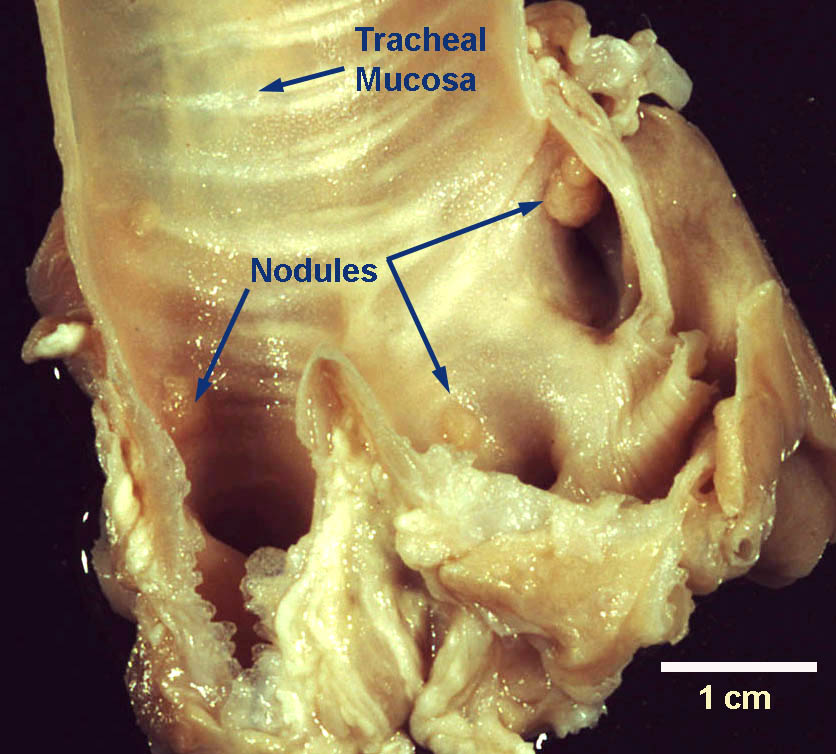

Adults of the nematode Oslerus (Filaroides) osleri live in nodules beneath the tracheal mucosa of dogs in many parts of the world, including Canada, and in coyotes in North America.

Summary

Taxonomy

Phylum: Nematoda

Class: Secernentea

Order: Strongylida

Superfamily: Metastrongyloidea

Family: Filaroididae

The Superfamily Metastrongloidea contains many of the lung nematodes of domestic animals, including Metastrongylus species in pigs, Muellerius capillaris of sheep and the other protostrongylids of domestic and free-ranging ungulates, Aelurostrongylus abstrusus of cats, but not species within the genus Dictyocaulus.

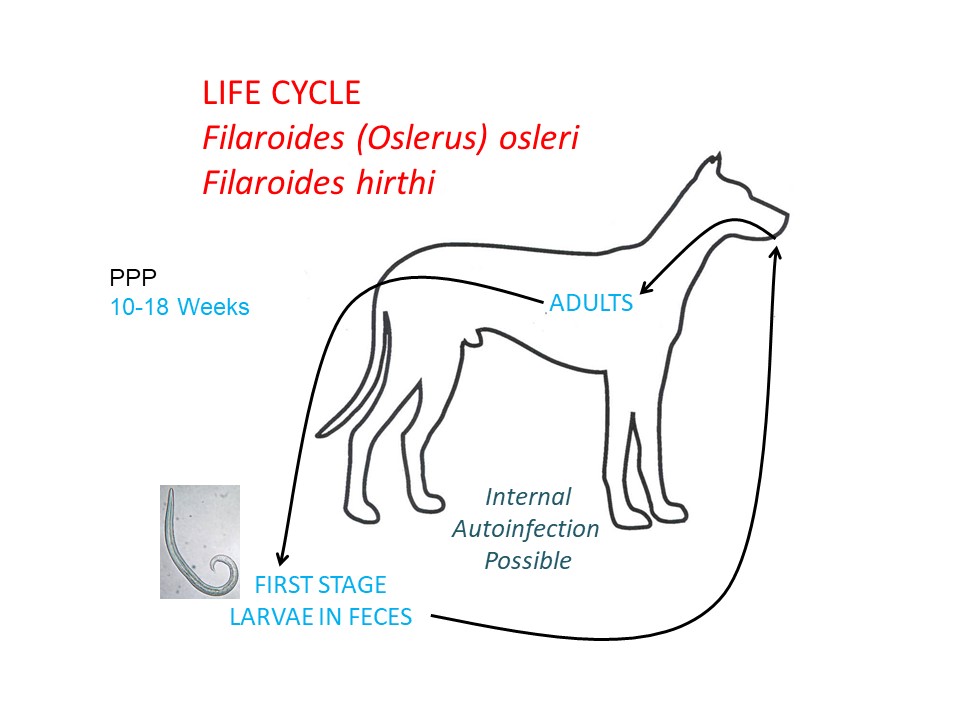

Oslerus osleri is an unusual metastrongylid in that it has a direct life cycle.

Note: Our understanding of the taxonomy of parasites is constantly evolving. The taxonomy described in wcvmlearnaboutparasites is based on Deplazes et al. eds. Parasitology in Veterinary Medicine, Wageningen Academic Publishers, 2016.

Morphology

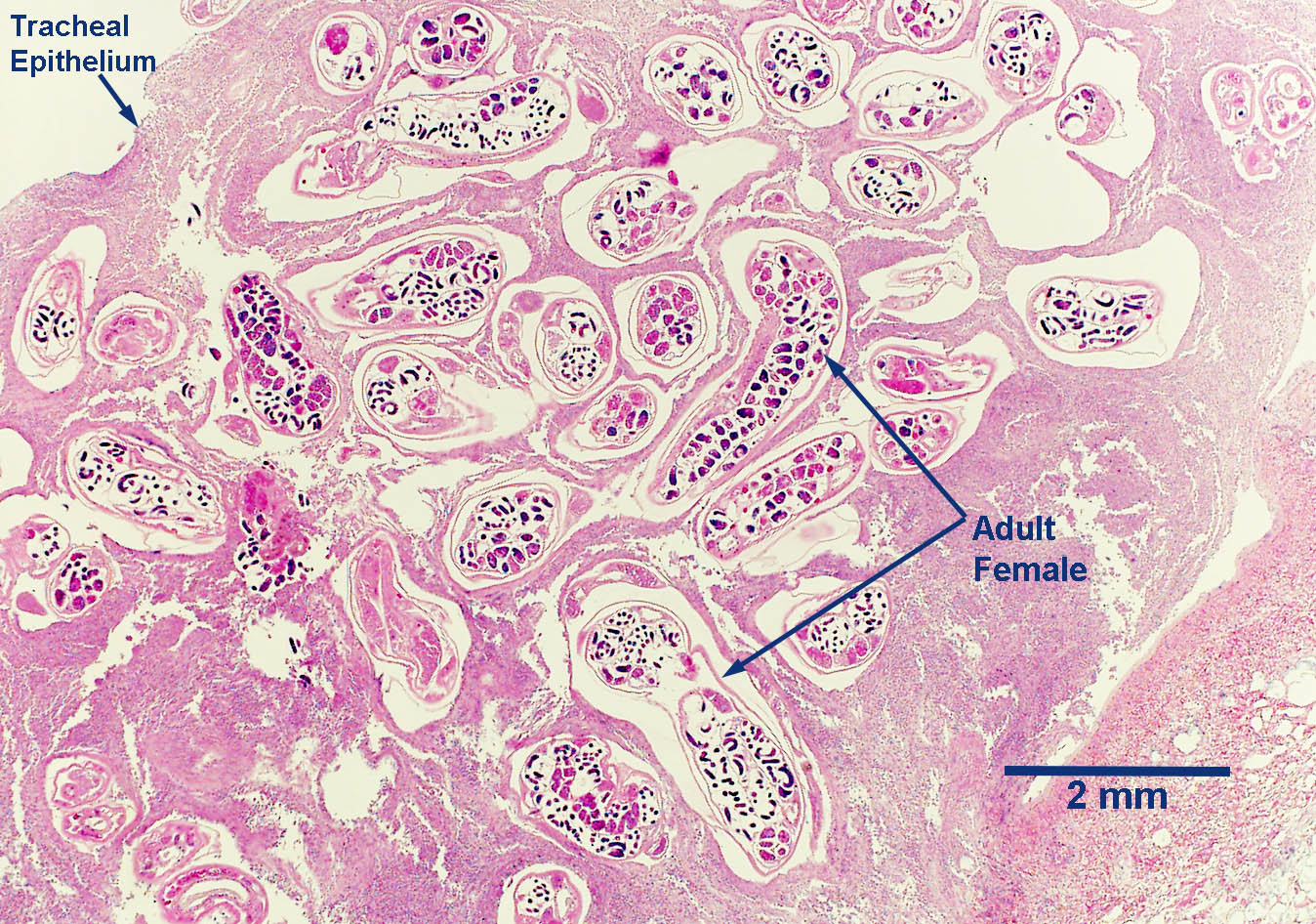

Adult O. osleri are very small, to approximately 5 mm (males) and 15 mm (females) in length, and they are tightly coiled in the tracheal nodules in which they live.

Nodule Section

First-stage larvae of O. osleri are approximately 230 to 265 µm in length and have a characteristic tail. They can easily be distinguished microscopically from the larvae of Strongyloides stercoralis, which have a rhabditiform pharynx.

Host range and geographic distribution

Life cycle - direct

Epidemiology

Pathology and clinical signs

Diagnosis

Treatment and control

Effective control of O. osleri in breeding kennels can be very difficult because it is usually necessary to interrupt the very close contact between a dam and her suckling pups. Recognition of the infection in the dams and appropriate treatment, coupled with efforts to maintain a clean environment, is also helpful. The significance of autoinfection has not been explored for O. osleri, but is known to be a problem with the closely related F. hirthi.