Rhipicephalus sanguineus: brown dog tick

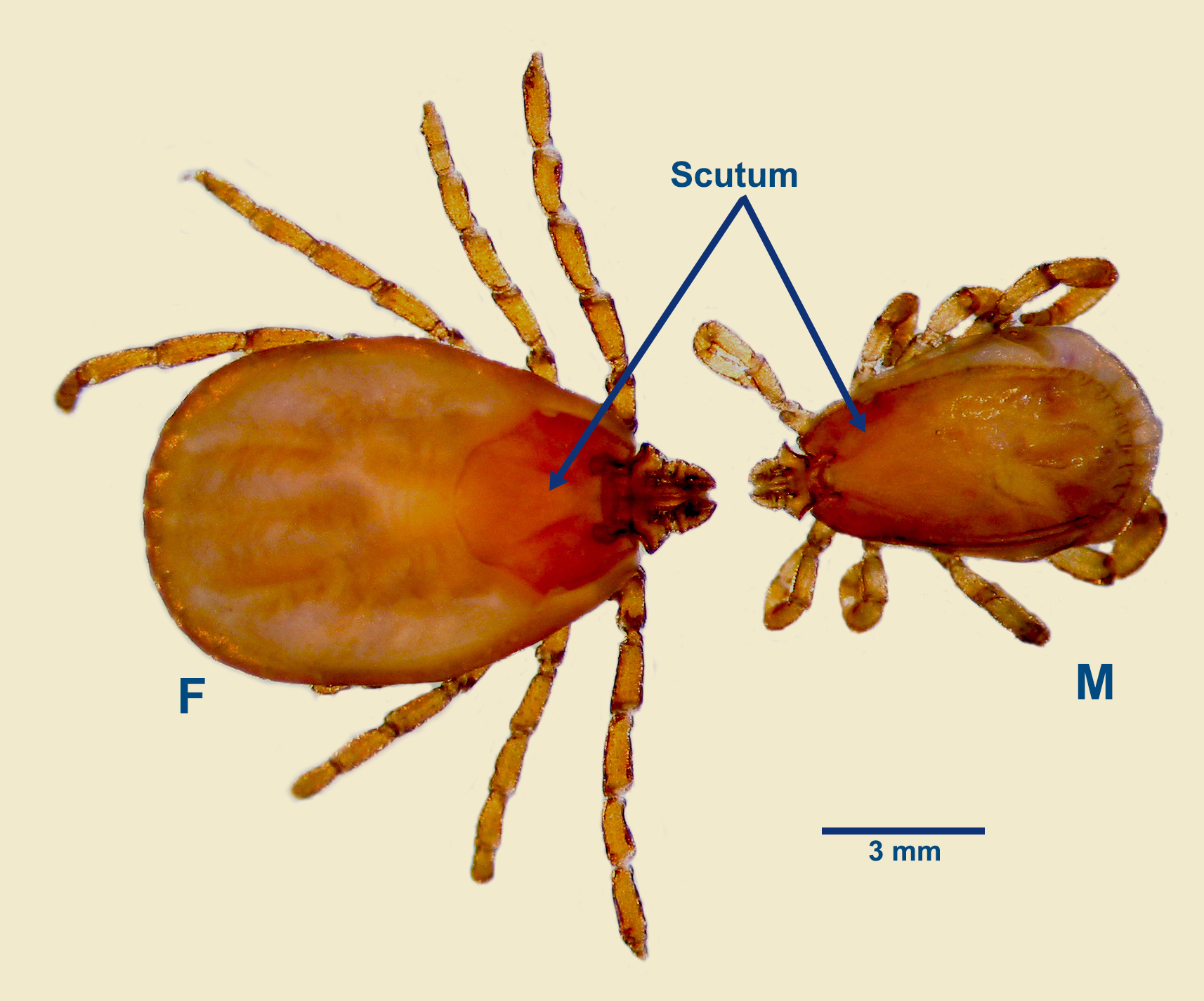

Rhipicephalus sanguineus, the brown dog tick, is a medium sized (unfed adult females are 4-5 mm long) yellowish-brown to reddish-brown tick with a dark inornate brown scutum.

Summary

Taxonomy

Phylum: Arthropoda

Subphylum: Amandibulata

Class: Arachnida

Subclass: Acari

Order:Metastigmata

Family: Ixodidae

Subfamily: Rhipicephalinae

As arachnids, ticks are closely related to mites and spiders. Other members of subfamily Rhipicephalinae present in Canada include Dermacentor andersoni, D. variabilis, and D. albipictus. Elsewhere in the world, closely related Boophilus spp. ticks are very important in livestock Note: Our understanding of the taxonomy of parasites is constantly evolving. The taxonomy described in wcvmlearnaboutparasites is based on Deplazes et al. eds. Parasitology in Veterinary Medicine, Wageningen Academic Publishers, 2016.

Morphology

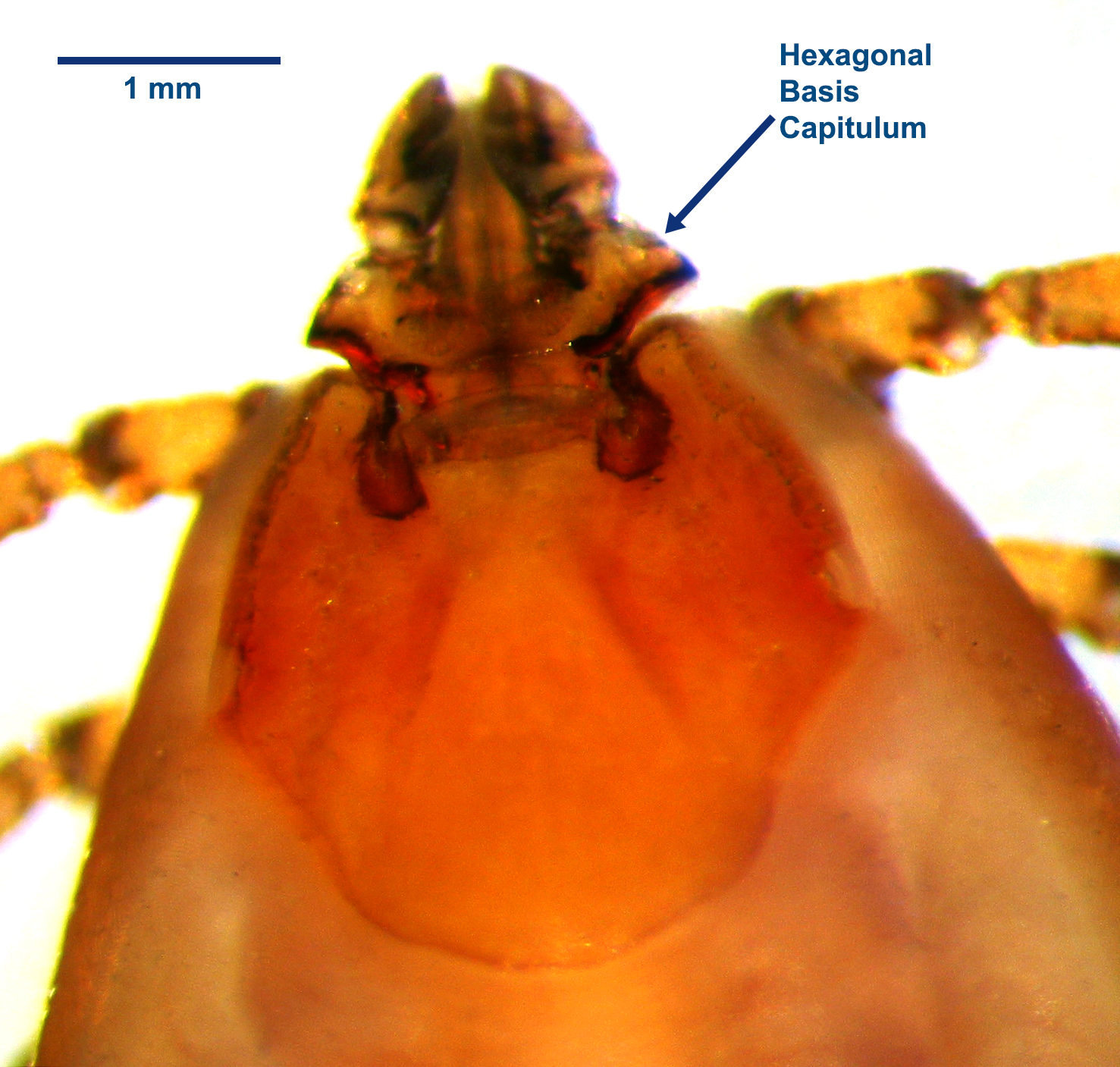

Rhipicephalus sanguineus, the brown dog tick, is a medium sized (unfed adult females are 4-5 mm long) yellowish-brown to reddish-brown tick with a dark, inornate brown scutum. The larvae have six legs while the nymphs and adults have eight legs. It has festoons, distinctive eyes and the basis capituliis hexagonal (Darth Vader helmet).

Host range and geographic distribution

Life cycle

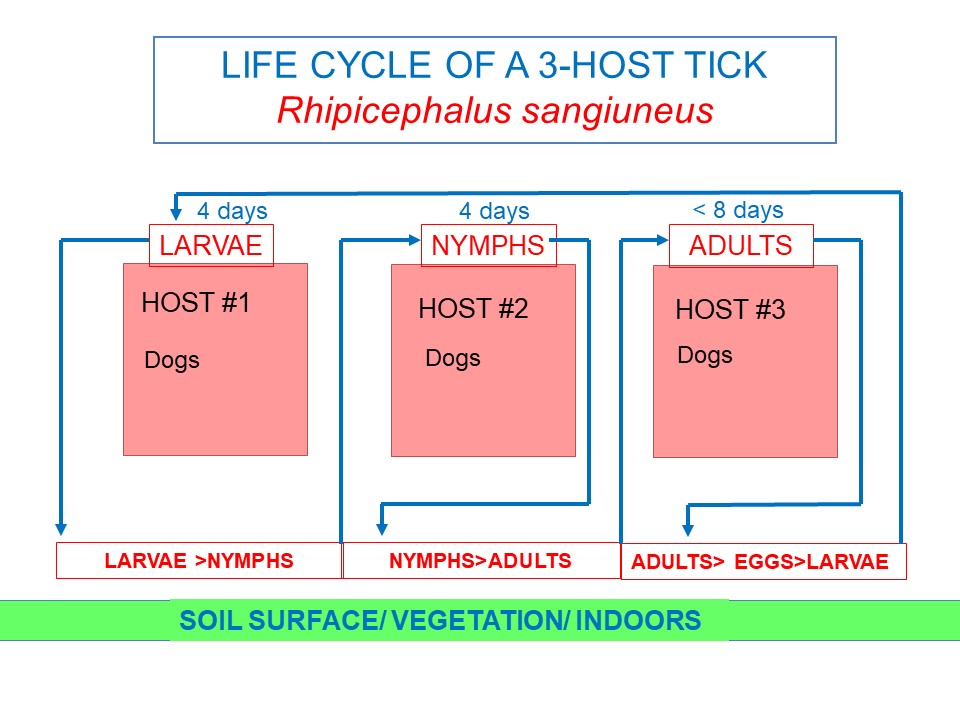

Rhipicephalus sanguineus is a three-host tick with each stage of the tick life cycle leaving the host to moult prior to finding another host. It is possible to find all three life stages on dogs and they may even be found on the same dog at one time. This species, particularly the larvae and nymphs, can, however, feed on other hosts. Unusually for ticks, R. sanguineus can complete its life cycle totally indoors, including in homes and kennels.

Engorged female ticks lay eggs in the environment, often in cracks and crevices in areas frequented by infested dogs. Larvae hatching from these eggs will attach to the host to feed (about 4 days) then drop off into the environment and molt to nymphs. The nymphs will attach to dogs, feed (about 4 days), fall off and molt to adults. The adult ticks attach to dogs, feed (about 8 days but often longer), mate and fall off to lay eggs in the environment. The entire life-cycle can be completed in as little as 2 months but normally takes longer (4-5 months) if ticks of all stages are not able to find an appropriate host. Unfed ticks are able to survive many months in the environment (larvae - approximately 253days, nymphs – 97 days, adults - 568 days).

Epidemiology

Pathology and clinical signs

This tick is also a vector for protozoans causing canine piroplasmosis (Babesia canis) and old world canine hepatozoonosis (Hepatozoon canis), and bacteria, including those causing Rocky Mountain spotted fever (Rickettsia rickettsi), canine pancytopenia (Erlichia canis), and anaplasmosis(Anaplasma platys). Usually the larva or nymph acquires the infectious agent from a host. The agent is retained through the moult – transstadial transmission – and then passed on to the next host when the tick feeds.

Diagnosis

In Canada, dogs with a history of travel to the southern USA, Mexico, the Mediterranean, or the tropics is suggestive. If large numbers of ticks are present, then owners may find engorged ticks on the dog. Adults are found commonly around the head and ears of infested dogs. The smaller, and harder to find, larvae and nymphs seem to prefer the legs, chest and belly of the host. Often dog owners do not recognize that their residence or kennel is infested until they notice ticks crawling up walls. A diagnostic laboratory can assist with the identification of any ticks found in a household. This inornate, festooned tick with short mouthparts is easily distinguished from native Dermacentor ticks, which have ornate scuta, and from native Ixodes ticks, which have no festoons and long, parallel mouthparts.

Treatment and control

Unlike ticks native to Canada, the outdoor environment is not a source of exposure to Rhipicephalus. Dogs traveling to endemic regions should be placed on effective tick preventatives to avoid contracting these foreign ticks, and dogs returning from endemic regions should be carefully screened and treated prior to entry into Canada. Once introduced, efforts must focus on the indoor environment and treatment of all in-contact dogs. The treatments of choice include topical or oral isoxazolines and newer macrocylic lactones. There are a number of older products including collars, powders, shampoos and sprays (both for the pet and the residence) approved for use in Canada for the treatment and control of this tick. Some contain pesticides unsafe for cats and children, and household composition should be considered. It is important to remember to control both the infestation on the dogs in the household as well as controlling the infestation in the buildings that the dogs frequent, which may involve contracting an exterminator.

Public health significance

References

Spencer, GJ. 1960. The brown dog-tick, Rhipicephalus sanguineus (Latr.), in Vancouver. Journal of the Entomological Society of British Columbia 57: 64-65. https://journal.entsocbc.ca/index.php/journal/article/viewFile/1363/1441

Drexler N, Miller M, Gerding J, Todd S, Adams L, et al. (2014) Community-Based Control of the Brown Dog Tick in a Region with High Rates of Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, 2012–2013. PLOS ONE 9(12): e112368. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0112368