Strongyloides stercoralis

The nematode Strongyloides stercoralis is primarily a parasite of people, but also occurs in dogs and sometimes cats.

Summary

Taxonomy

Class: Secernentea

Order: Rhabditida

Family: Strongyloididae

As well as S. stercoralis, the genus includes several other species of Strongyloides that infect cattle, sheep, horses, pigs and a range of other mammals, as well as amphibians, reptiles and birds. All species of Strongyloides have a similar structure and life cycle. Most rhabditid nematodes are free-living, and under some circumstances parasitic Strongyloides species have free-living adults in their life cycles. Also related is the genus Pelodera, which is free-living, but larvae of which occasionally cause cutaneous larva migrans in a variety of hosts, especially dogs.

Note: Our understanding of the taxonomy of parasites is constantly evolving. The taxonomy described in wcvmlearnaboutparasites is based on Deplazes et al. eds. Parasitology in Veterinary Medicine, Wageningen Academic Publishers, 2016.

Morphology

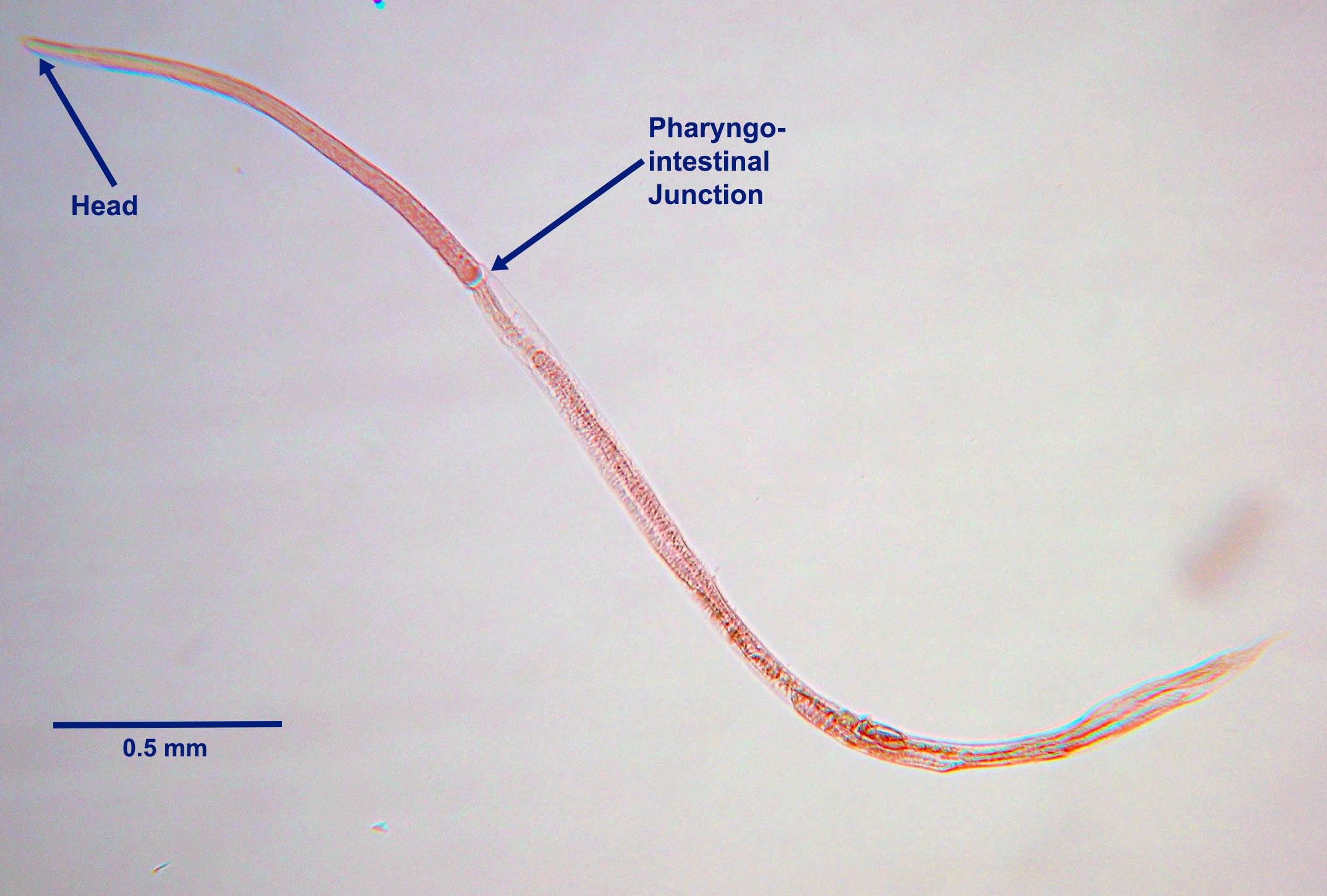

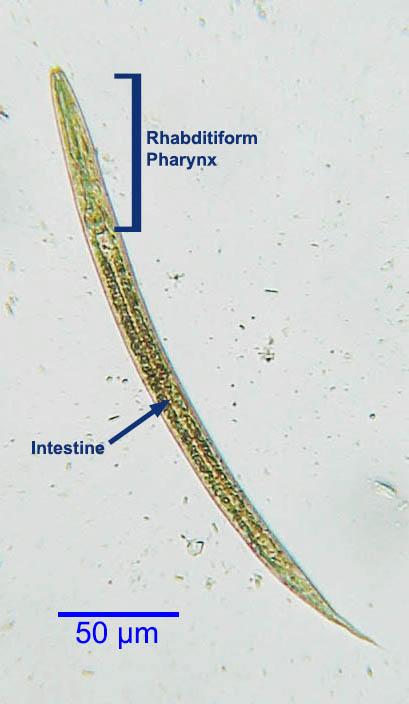

The rhabditiform first-stage larvae of S. stercoralis passed in the feces of an infected dog (the eggs hatch in the intestinal lumen) are approximately 300 µm long with a rhabditiform pharynx.

Host range and geographic distribution

Strongyloides stercoralis is a parasite that occurs in people and dogs in warm and humid areas. The parasite is found only occasionally in these host species in Canada, likely acquired through travel to tropical or subtropical regions (potentially the southeastern USA). Infection with S. stercoralis in dogs is more common than is clinical disease, and it is possibly underdiagnosed as it would not generally be detected on routine fecal flotation.

Life cycle - direct

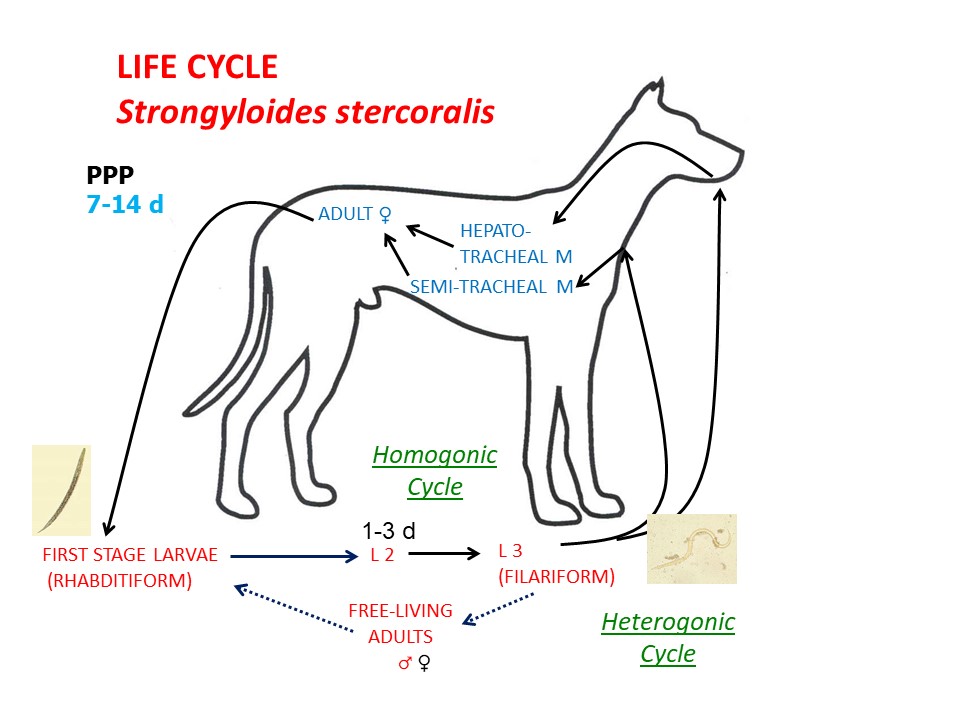

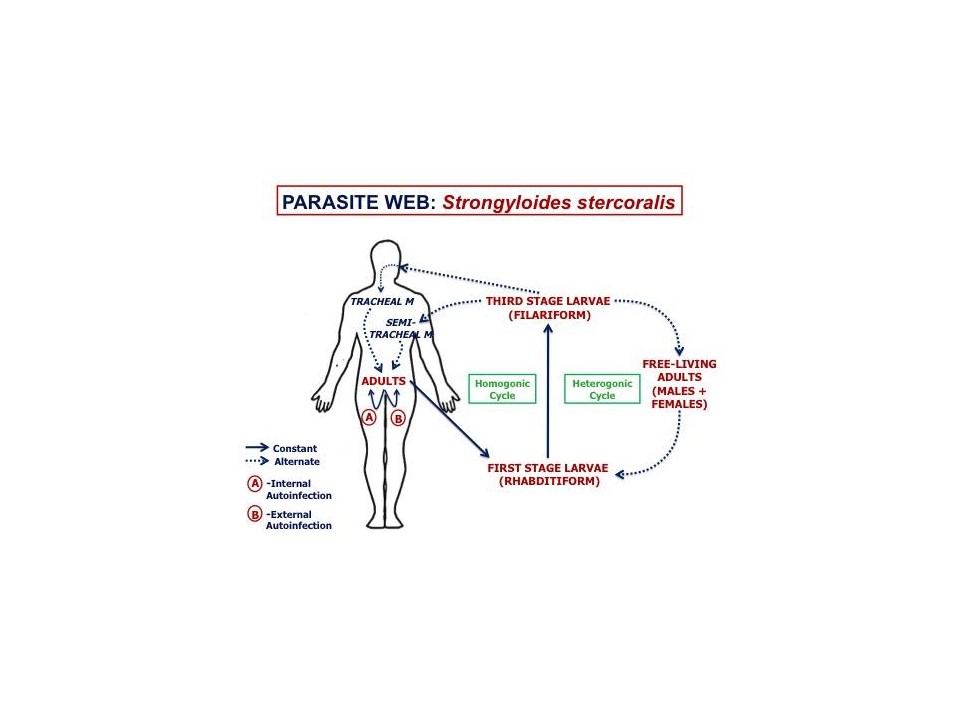

Adult female S. stercoralis are located deep in the mucosa of the small intestine. These females reproduce by parthenogenesis, producing both male and female offspring. The eggs hatch in the GI tract, and first-stage (rhabditiform) larvae (L1) are passed in the feces. Male L1 proceed to become free-living adult males. Female larvae can either moult twice, developing into infective third-stage (filariform) larvae (homogonic cycle), or moult two more times and develop into free-living adult females (heterogonic cycle). Free-living adults mate once and produce female rhabditiform larvae which develop into infective filariform L3. Translation from L1 to L3 can occur rapidly, in a matter of days. Infection of the dog follows skin penetration by, or ingestion of, filariform female L3. In the dog, these larvae migrate in the vasculature through the liver and lungs, where they break out from the branches of the pulmonary artery into the airways, are coughed up and swallowed and move to the small intestine, where they complete their development to adult females. The prepatent period is 7-14 days. Pre-natal infection of pups with S. stercoralis does not occur, but trans-mammary infection occurs in females infected immediately post-partum.

In people, and perhaps in dogs, S. stercoralis is capable of auto-infection, where rhabditiform larvae become infective filariform larvae (due to rapid translation) either in the intestinal lumen or in the peri-anal area. In people, particularly those who are immunosuppressed, autoinfection can result in large and/or very persistent infections.

Epidemiology

The free-living life cycle of Strongyloides stercoralis is favored under warm, moist environmental conditions that support the development and survival of the free-living larval stages and adults. The stimuli that push the rhabditiform larvae of S. stercoralis into the homogonic or heterogonic cycle are not fully understood, but are probably some combination of environment, parasite genotype and possibly host factors. The transmission of S. stercoralis is also enhanced by sub-optimal hygiene, which brings the host into contact with infective larvae. Prevalence in dogs in Canada is low; it has been reported at very low prevalence in coughing dogs in Ontario.

Pathology and clinical signs

Diagnosis

Treatment and control

There are no products available for dogs in Canada that are labeled for S. stercoralis. Macrocyclic lactones are likely to be quite effective.

For the control of S. stercoralis, appropriate treatment protocols and the maintenance of a clean environment are very important.

Public health significance

Strongyloides stercoralis is zoonotic, and can be transmitted from dogs to people and vice versa. In the human host, the filariform larvae can cause cutaneous larva migrans as they penetrate the skin, very large burdens of migrating larvae can cause significant lung pathology, and the adult female S. stercoralis can be associated with GI symptoms.

Strongyloides stercoralis is a particular problem in people who are immuno-suppressed, in part because of auto-infection. The parasite is a potentially very serious pathogen in these individuals.