Toxocara canis

Toxacara canis is an ascarid nematodes of the small intestine of dogs and free-ranging canids. It occurs around the world, including Canada, although in the northern regions of this country it is to some extent replaced by Toxascaris leonina.

Summary

Toxacara canis is an ascarid nematode of the small intestine of dogs and free-ranging canids. It occurs around the world. It is the most common helminth parasite of dogs in Canada, with prevalences ranging from 1-2% in healthy, owned, adult pets to over 20% in young, shelter or free-ranging dogs. In northern Canada, this parasiteis to some extent replaced by the non-zoonotic ascarid nematode Toxascaris leonina. Toxocara canis has a direct life cycle, sometimes involving mammal and bird paratenic hosts. The infective stage is the third-stage larva in the egg, which takes several weeks to develop in the environment. Following ingestion, the eggs hatch and the larvae undergo a complex migration in the dog, the exact route depending on the age, immune, and hormonal statusof the dog, the size of the infective dose, and the infective stage (L3 in egg, L3 in paratenic host). In young pups, prenatally acquired larvae and larvae ingested in eggs undergo a hepatotracheal migration and complete their development to adults in the small intestine. As the pups age, there is a gradual transition of the larval migration route from hepatotracheal to somatic, in which most larvae complete their migrations in skeletal muscle and other tissues, and do not establish a patent GI infection. In the third trimester of pregnancy, these larvae enter the blood stream and infect the foetuses. These prenatal infections become patent when the pups are approximately two weeks old. Parasite prevalence and intensity are greater in young pups than in older animals. Clinical signs are, therefore, most common in pups and include GI disturbances, respiratory signs, poor-doing, and, rarely, seizures. Diagnosis is based on detecting eggs on fecal flotation and/or adults in feces/vomit, supplemented by coproantigen or coproPCR tests. Treatment of pups is recommended at 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, 16, 20, and 24 weeks of age. Subsequently, treatment for GI nematodes is only recommended for dogs at high risk of exposure (free-roaming, coprophagic, raw meat diet, etc), dogs in high risk households (young, immunocompromised, or pregnant household members), and dogs that test positive on fecal testing. There are several products approved in Canada for treatment of intestinal infections, and there are also protocols for the extralabel use of drugs for treating pregnant females. Ingestion of infective eggs of T. canis by people can result in visceral, ocular or occult larva migrans, all of which can produce severe clinical signs. All of these conditions appear to be very rare in Canada.

Taxonomy

Phylum: Nematoda

Class: Secernentea

Order: Ascaridida

Superfamily: Ascaridoidea

Family: Ascarididae

SubFamily: Toxocarinae

Toxocara canis is an ascarid nematode, related to the other ascarids in dogs and cats (Toxocara cati and Toxascaris leonina), and to the ascarids of horses (Parascaris equorum), pigs (Ascaris suum), and people (Ascaris lumbricoides).

The adults of these various ascarids are large to very large, females are highly fecund, and their eggs are long-lived, thick-shelled and resistant to adverse environmental conditions. Additionally, their life cycles have many similarities, including larval development to the infective stage within the egg, and complex larval migration routes in the mammalian hosts.

Note: Our understanding of the taxonomy of parasites is constantly evolving. The taxonomy described in wcvmlearnaboutparasites is based on Deplazes et al. eds. Parasitology in Veterinary Medicine, Wageningen Academic Publishers, 2016.

Morphology

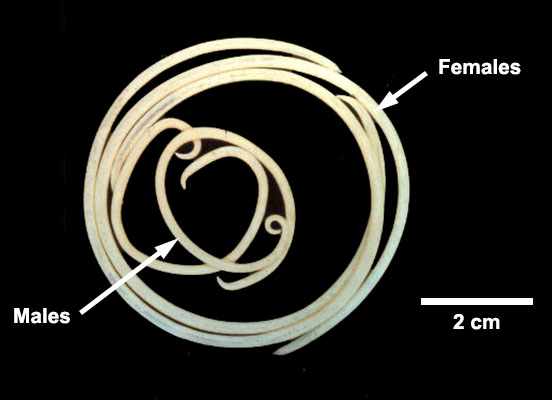

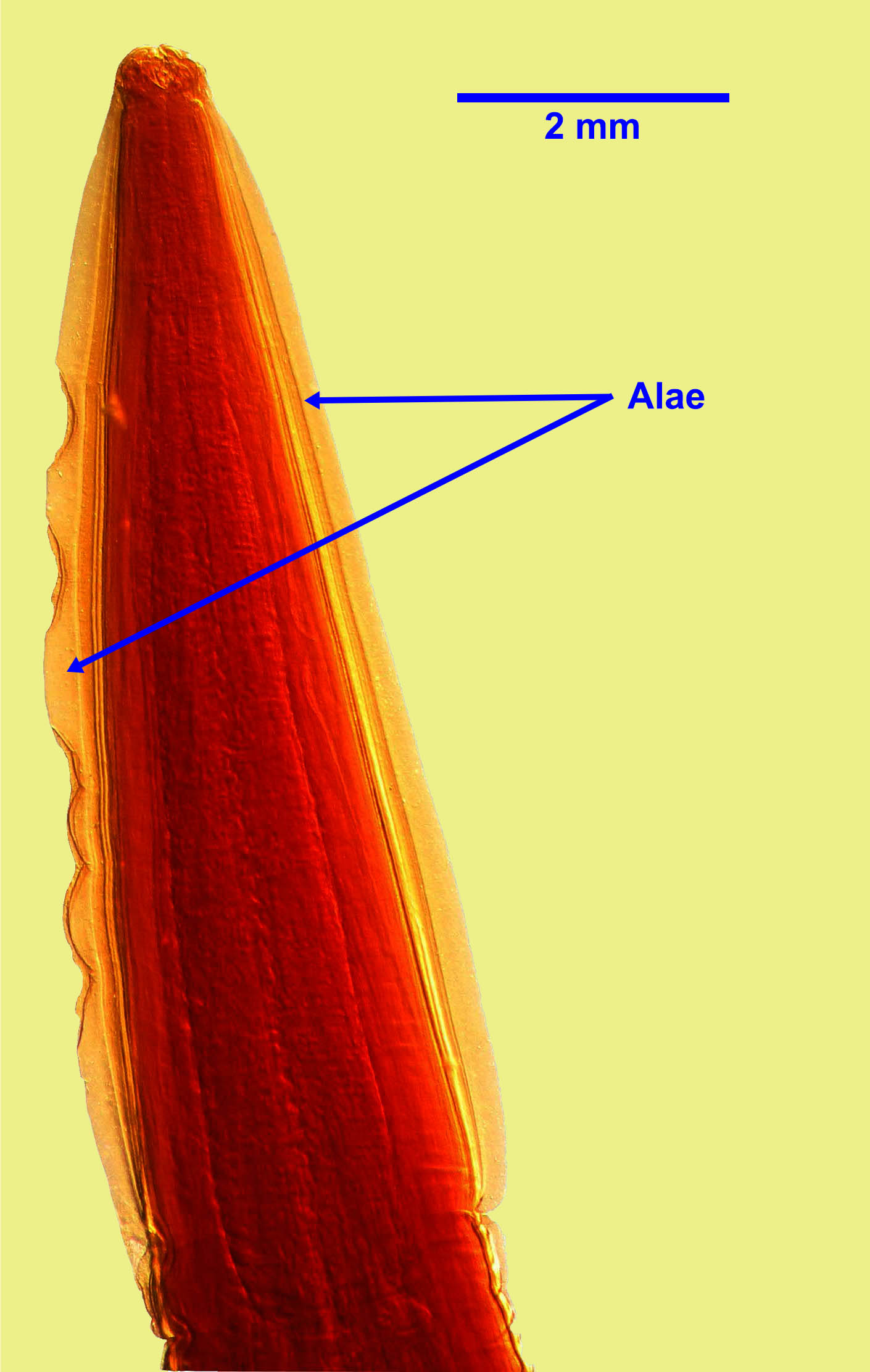

Adult T. canis are up to approximately 10 cm (males) and 18 cm (females) long and easily visible to the naked eye. Males and females have two long and narrow lateral cervical alae and three “lips” at the anterior end.

Anterior alae

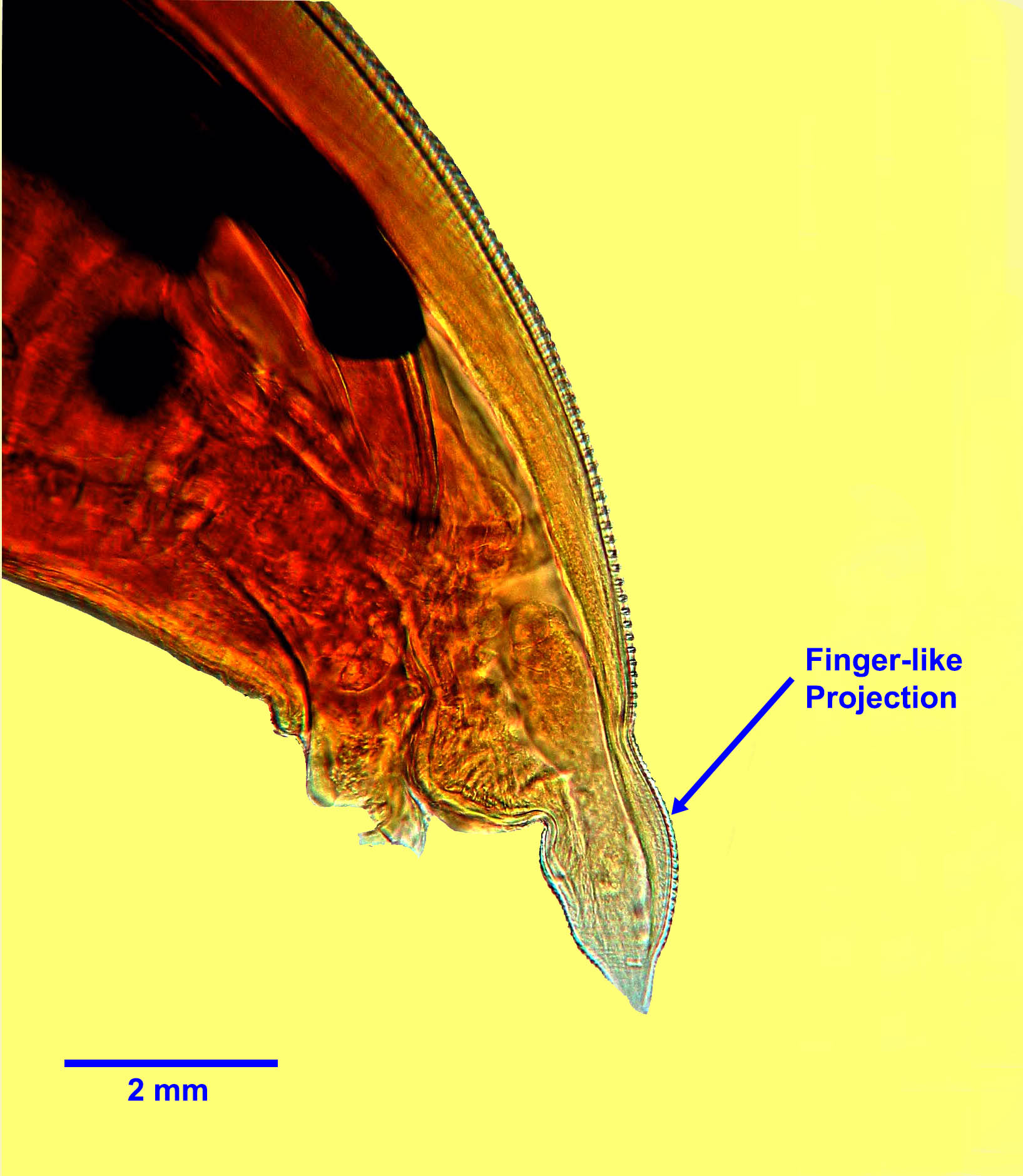

Males have a short finger like projection at the posterior end.

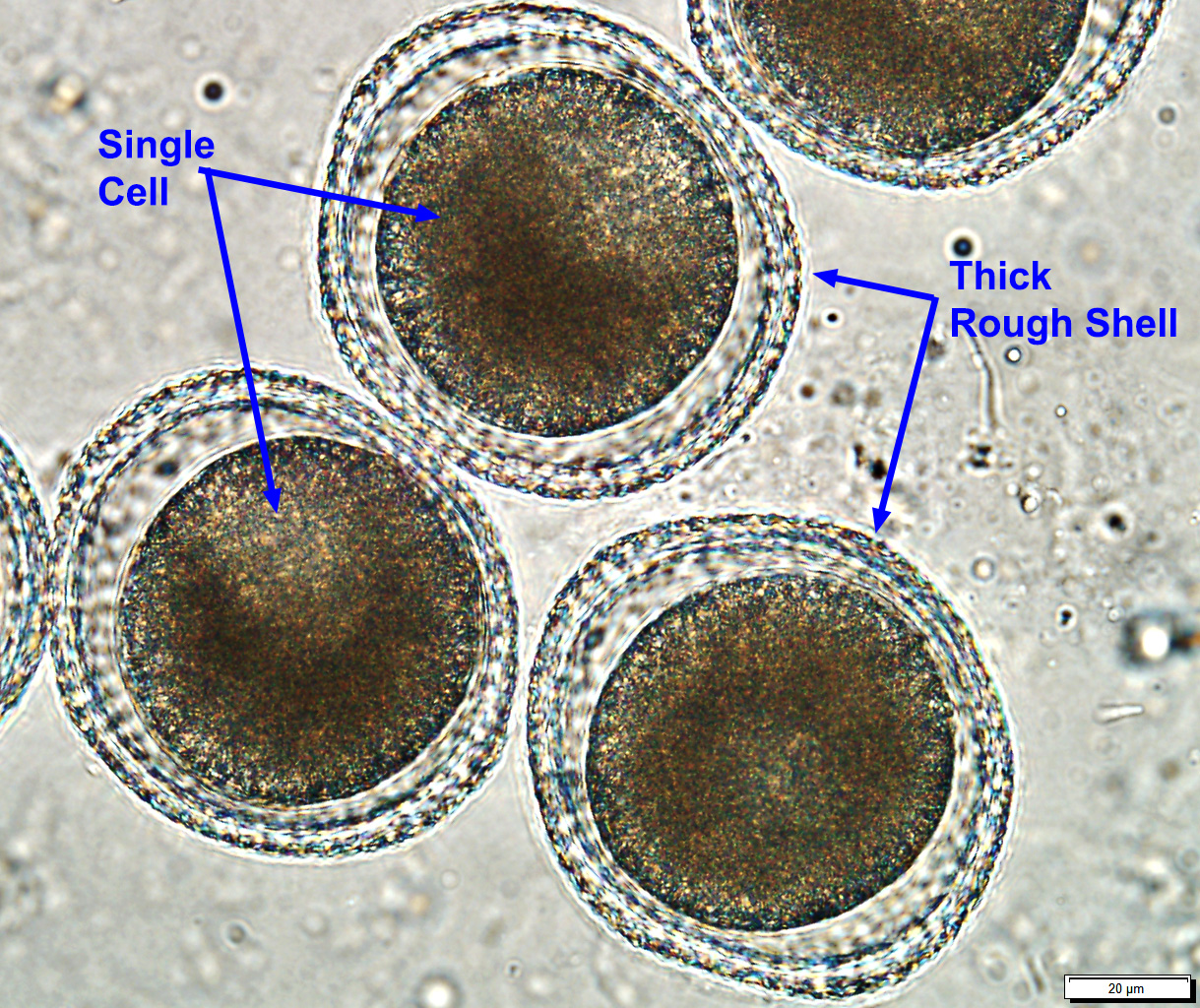

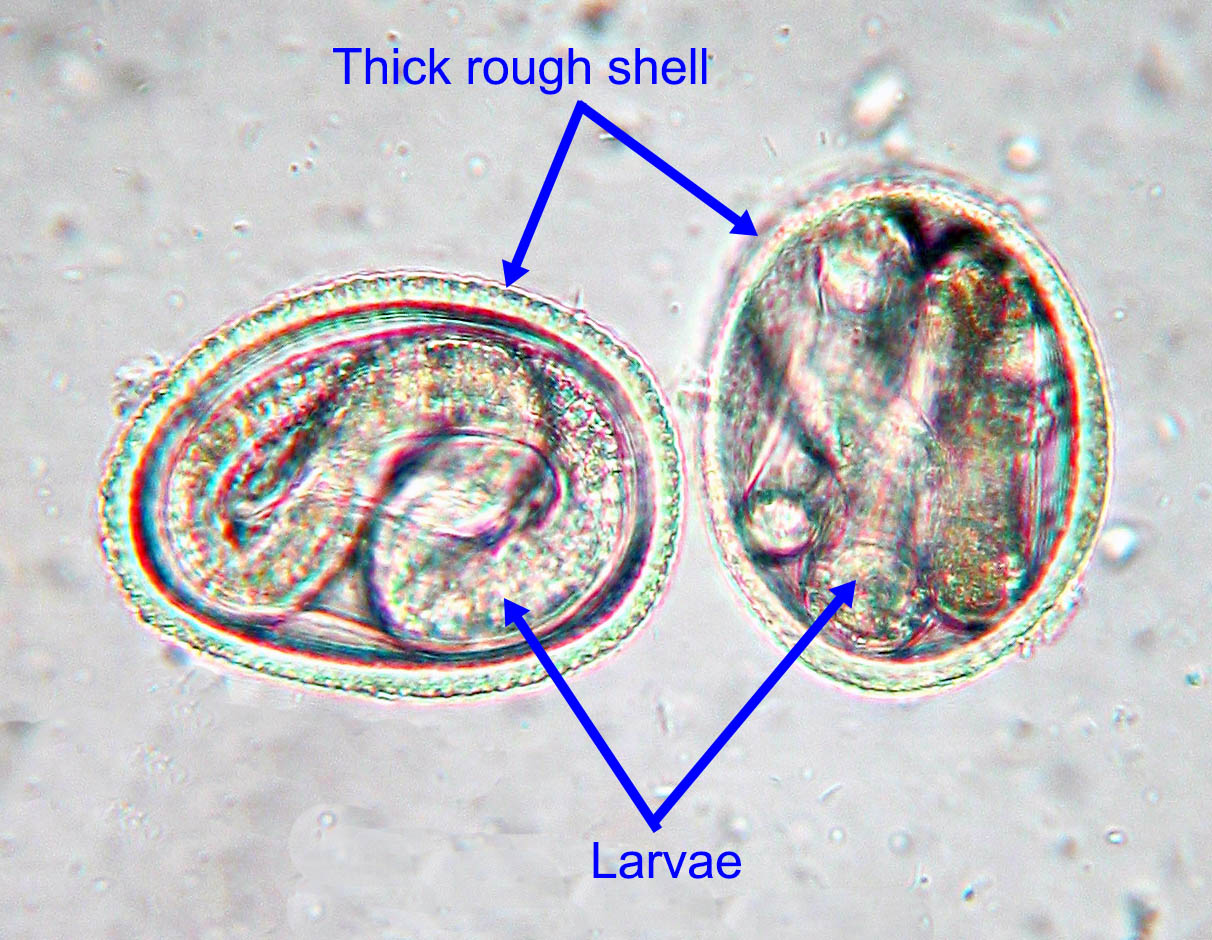

Eggs measure approximately 90 by 75 µm, and are sub-spherical with a thick, rough shell (“golf ball” appearance). Each egg contains one or two cells when freshly passed.

Host range and geographic distribution

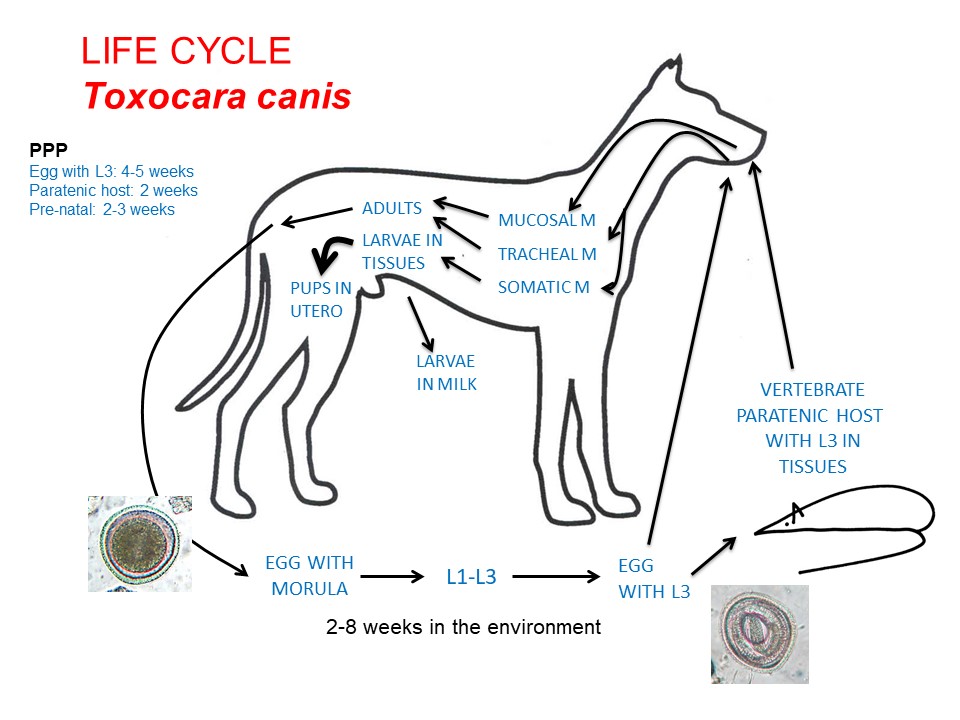

Life cycle - direct or congenital

Adult T. canis are located in the small intestine of the dog, and eggs leave the host in the feces. An infective third-stage larva develops in each egg after 3-4 weeks in ideal environmental conditions. This development rate is temperature-dependent.

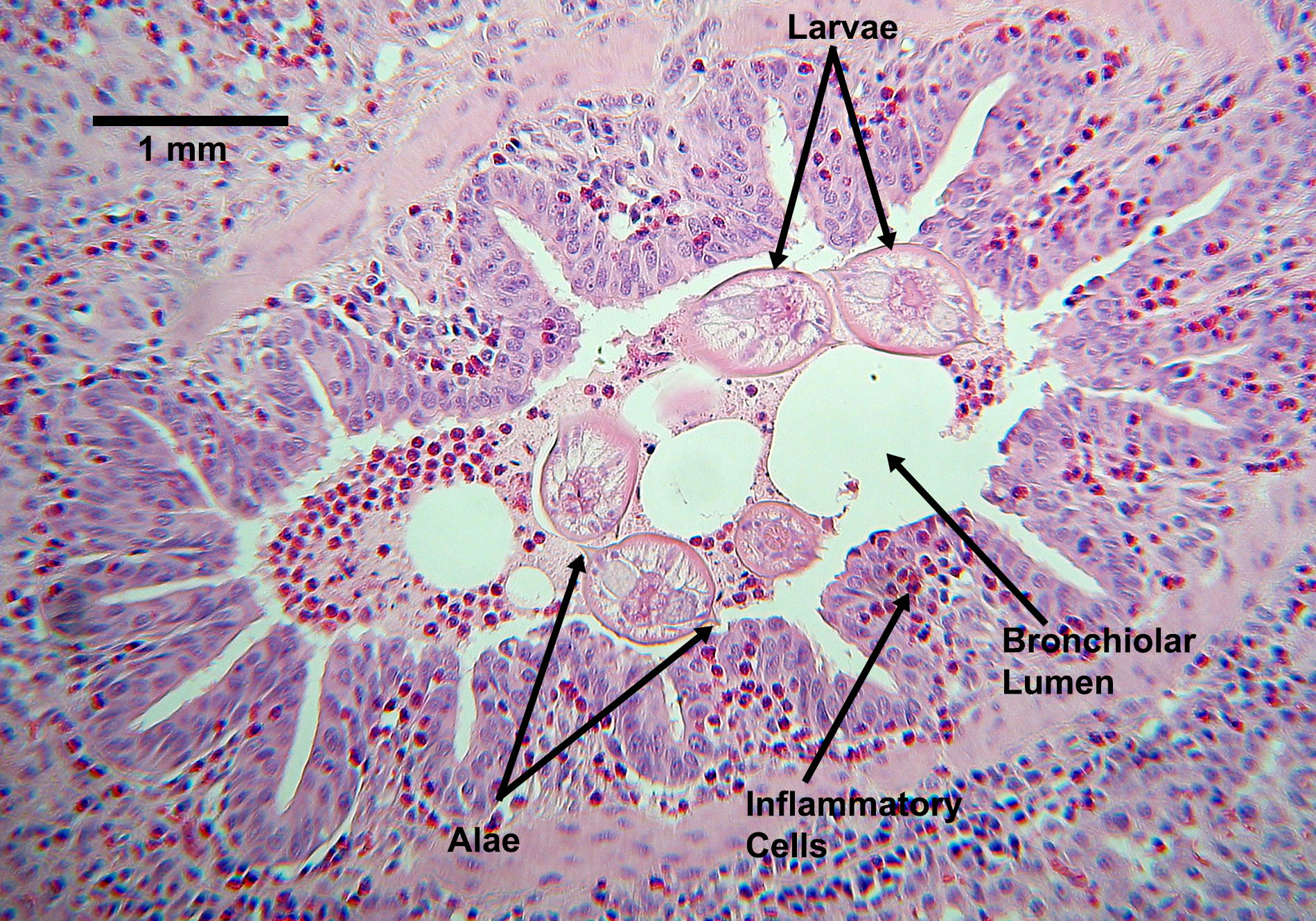

Following ingestion of infective L3 within eggs, in pups less than approximately 3 months old the larvae migrate via the vasculature through the liver to the lungs, where they break out from the branches of the pulmonary artery into the airways, are coughed up, swallowed and mature to adults in the GI system – this is the hepatotracheal migration (pre-patent period 4-5 weeks). In older dogs (> approximately 6 months), initially larvae follow a similar migration route, but once in the lungs do not enter the airways but leave the lungs in the pulmonary veins and are distributed in the bloodstream to a variety of tissues – this is a somatic migration. Between 3 and 6 months of age, there is a gradual transition from primarily tracheal to primarily somatic migration.

Ascarid larvae migrating in a lung

If a female dog becomes pregnant, larvae in the tissues are mobilized at the start of the third trimester, enter the vasculature, cross the placenta and enter the livers of the fetal pups. This is pre-natal infection. When the pups are born, the larvae undergo a hepatotracheal migration and mature to adults in the intestine. Eggs can be present in the feces of pre-natally infected pups by 2-3 weeks after birth. Less commonly than pre-natal infection, s larvae infecting the female in late pregnancy/early lactation can enter the mammary glands of the female and be transmitted to suckling pups in the milk during the first four or five weeks of lactation – this is trans-mammary infection. Nursing females may occasionally ingest eggs containing L3, L4, L5, or adult nematodes passed in the feces or vomit of the pups. These, as well as any larvae that were activated from the somatic tissues of the female during pregnancy and entered her intestine, can produce a usually transient patent infection in the female.

Larvated, infective eggs may also be ingested by a paratenic host, in which the larvae released follow a somatic migration. If the paratenic host is eaten by a dog, larvae are released, undergo a mucosal migration, and establish an adult infection in the dog’s GI system (pre-patent period 4 weeks). Paratenic hosts include a wide range of vertebrates, including small mammals, birds, livestock, and people.

These life cycle patterns mean that T. canis is generally more prevalent, and infections are more intense, in young pups than in older pups or adult animals. However, older animals can develop patent infections, especially if immunocompromised or malnourished.

Epidemiology

Pathology and clinical signs

In young puppies, especially those infected pre-natally, migrating larvae of T. canis in the lungs may be associated with respiratory signs. In untreated pups, adult parasites in the GI system can be associated with sub-optimal growth and development, poor body condition (“pot-belly”), and diarrhoea, as well as possibly ”seizures”. The pathogenesis of these clinical signs is not fully understood. In older dogs, neither adult parasites nor migrating larvae are commonly associated with clinical abnormalities, although multifocal retinitis (ocular larva migrans) associated with T. canis larvae has been reported.

Diagnosis

Treatment and control

The aims of any treatment and control for Toxocara canis are to minimize the effects of the parasite on dogs, to minimize parasite transmission among dogs and between dogs and people, and to decrease environmental contamination with the hardy eggs. Several products are approved in Canada to treat the life cycle stages of T. canis in the GI system, and these products are used as part of an overall treatment and control program for GI nematodes. Extra-label use of fenbendazole or macrocyclic lactones, particularly ivermectin or moxidectin, is sometimes used in pregnant females to prevent prenatal transmission, especially if she has had previously infected litters.

Current best practice guidelines from the Canadian Parasitology Expert panel are that young pups should be treated for roundworms at 2, 4, 6, and 8 weeks of age, then monthly to 6 months of age. One of the problems with starting the treatment schedule at two or three weeks of age is that many pups and kittens do not have contact with a veterinarian until they are six or eight weeks old. Providing the drugs to breeders with encouragement towards good compliance can help address this problem.

For dogs 6 months and older, recommendations differ depending on the risk profile of the dog and geographic location. In the USA, many parasitologists and veterinarians recommend monthly treatments continuing year-round for the life of the dog. This schedule is thought to increase compliance and also coincide with monthly administration of heartworm preventatives. In most of Canada, where heartworm is not endemic and where infection pressure for other parasites is relatively low, a risk based approach is recommended. Dogs which are free-ranging, coprophagic, fed raw meat diets, frequently exposed to heavily contaminated environments (dog parks), etc are considered high risk for exposure. Owners of service animals and animals in households that contain young children (under 3), pregnant, or immunocompromised people may have higher level of concern about parasitic zoonoses. In these cases (high risk dog and/or high risk household), test 1-2 times annually and treat at least 3-4 times a year. In older, low risk dogs in low risk households, test and treat yearly. It is also appropriate to treat only if eggs are detected on fecal examination +/- positive coproantigen or coproPCR tests, which have high sensitivity.

Other methods of control include regular removal of dog feces (as infective larvae take at least 2 weeks to develop), feeding only cooked or commercial diets, preventing dogs from hunting or scavenging wildlife and domestic livestock, and spaying female dogs, especially those with known positive litters.

Public health significance

Toxocara canis can be associated with ocular, visceral and occult larva migrans in people, the first particularly in young children. Human infection usually follows ingestion of infective eggs, and the clinical syndrome that develops depends on the primary location of the migrating larvae that hatch from these eggs. Rarely, human infections with T. canis are associated with the ingestion of tissues from animals and birds containing larval stages of the parasite (other paratenic hosts). Infection with T. canis in people (as detected serologically) appears to be much more common than is clinical disease. All three syndromes are very rare in Canada. Human infections with T. canis can be prevented by regular removal of dog feces (as infective larvae take at least 2 weeks to develop), good hand hygiene following handling of dogs and dog feces, washing all produce and cooking meat prior to consumption, and keeping dogs out of play areas used by children.

References

Jenkins. 2020. Chapter 31: Toxocara spp. in dogs and cats in Canada. Advances in Parasitology 109:641-653. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.apar.2020.01.026

Villeneuve, L. Polley, E.J. Jenkins, J.M. Schurer, J. Gilleard, S. Kutz, G. Conboy, D. Benoit, W. Seewald, F. Gagné. 2015. Parasite prevalence in fecal samples from dogs and cats across the Canadian provinces. Parasites and Vectors 8:281 doi:10.1186/s13071-015-0870-x.

Overgaauw P et al., (2013) Veterinary and public health aspects of Toxocara spp. Veterinary Parasitology 193: 198-403.

Gaunt, M. C., & Carr, A. P. (2011). A survey of intestinal parasites in dogs from Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. Canadian veterinary journal 52(5), 497–500.

Epe C (2009) Intestinal nematodes: biology and control. Veterinary Clinics of North America Small Animal Practice 39: 1091-1107.