Toxocara cati

Toxacara cati is an ascarid nematodes of the small intestine of cats and free-ranging felids. It occurs around the world, including Canada.

Summary

Taxonomy

Phylum: Nematoda

Class: Secernentea

Order: Ascaridida

Superfamily: Ascaridoidea

Family: Ascarididae

SubFamily: Toxocarinae

Toxocara cati is an ascarid nematode, related to the other ascarids in dogs and cats (Toxocara canis and Toxascaris leonina), and to the ascarids of horses (Parascaris equorum), pigs (Ascaris suum), and people (Ascaris lumbricoides).

The adults of these various ascarids are large (up to 30 cm in length), highly fecund, and their eggs are long-lived, thick-shelled and resistant to adverse environmental conditions. Additionally, their life cycles have many similarities, including larval development to the infective stage within the egg, and complex larval migration routes in the mammalian hosts.

Note: Our understanding of the taxonomy of parasites is constantly evolving. The taxonomy described in wcvmlearnaboutparasites is based on Deplazes et al. eds. Parasitology in Veterinary Medicine, Wageningen Academic Publishers, 2016.

Morphology

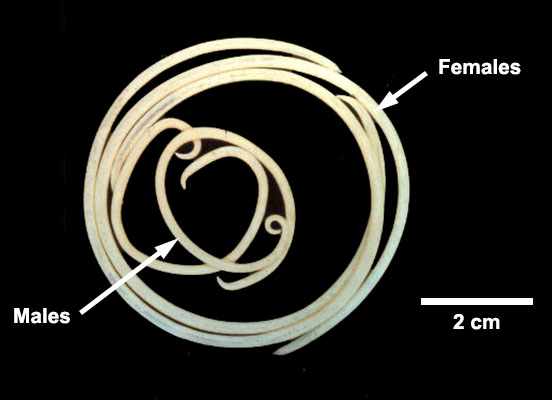

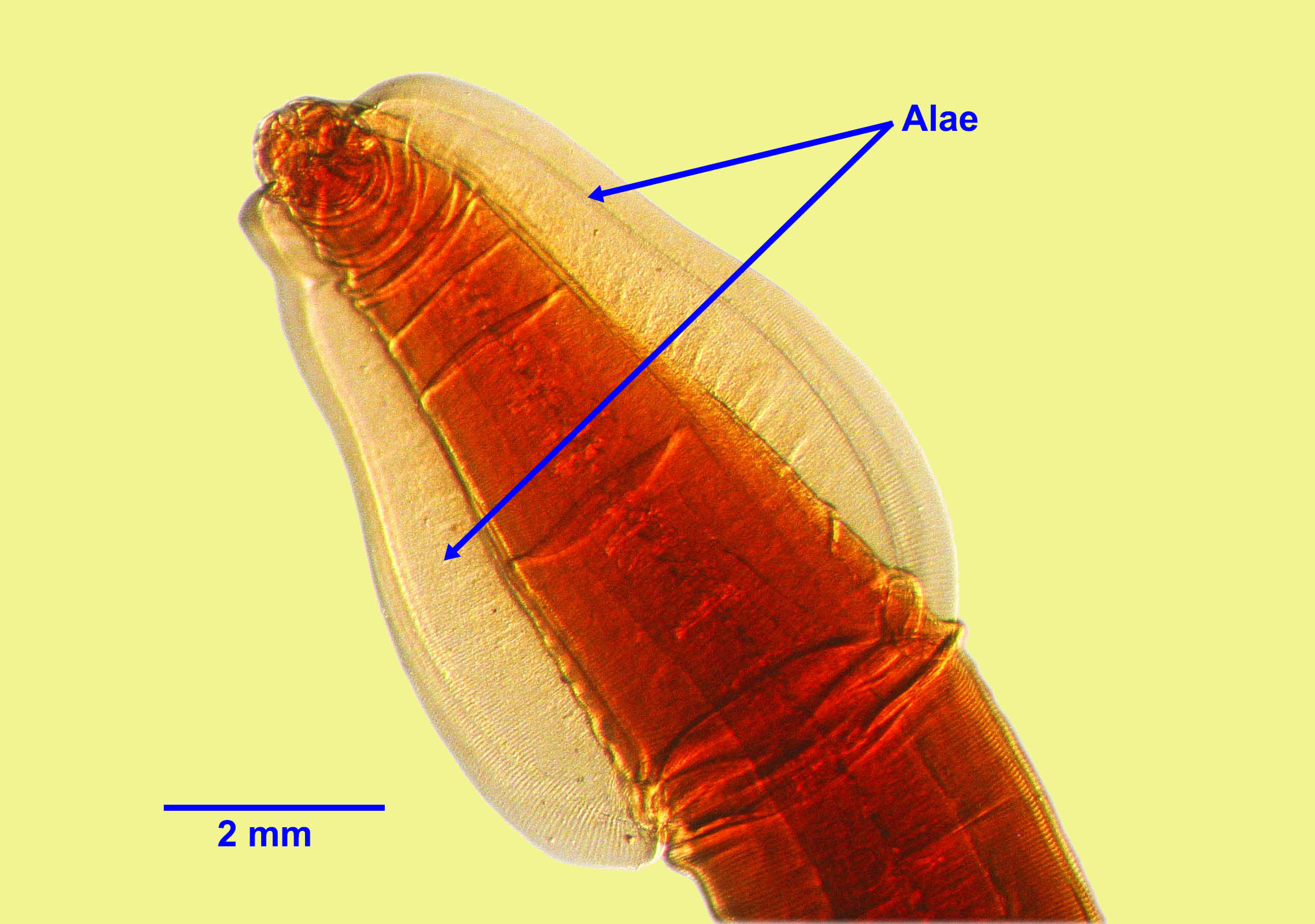

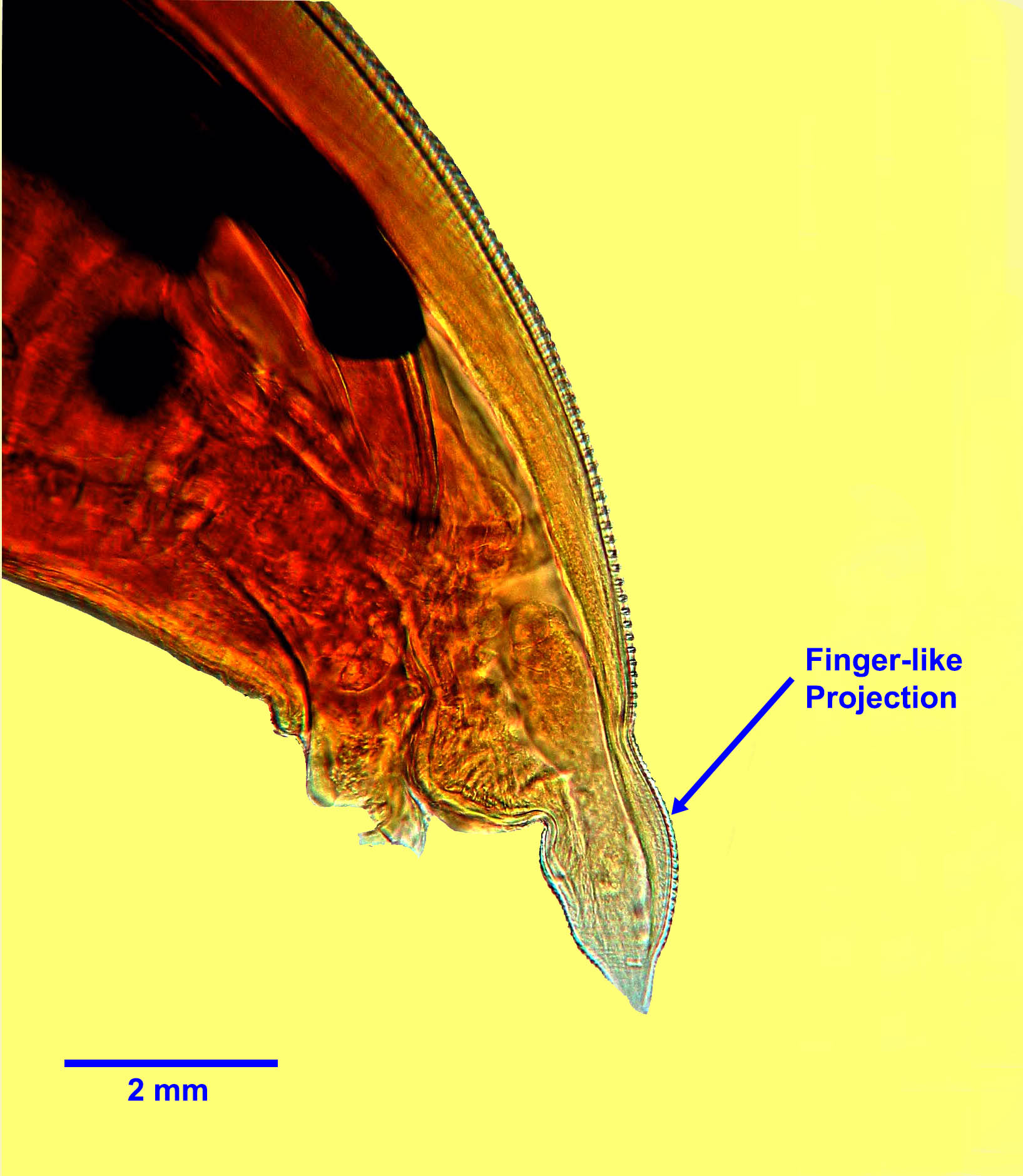

Adult T. cati are up to approximately 6 cm (males) and 10 cm (females) long and easily visible to the naked eye. Males and females have two broad, arrowhead-shaped lateral cervical alae at the anterior end, and three “lips”. Males have a short finger-like projection at the posterior end.

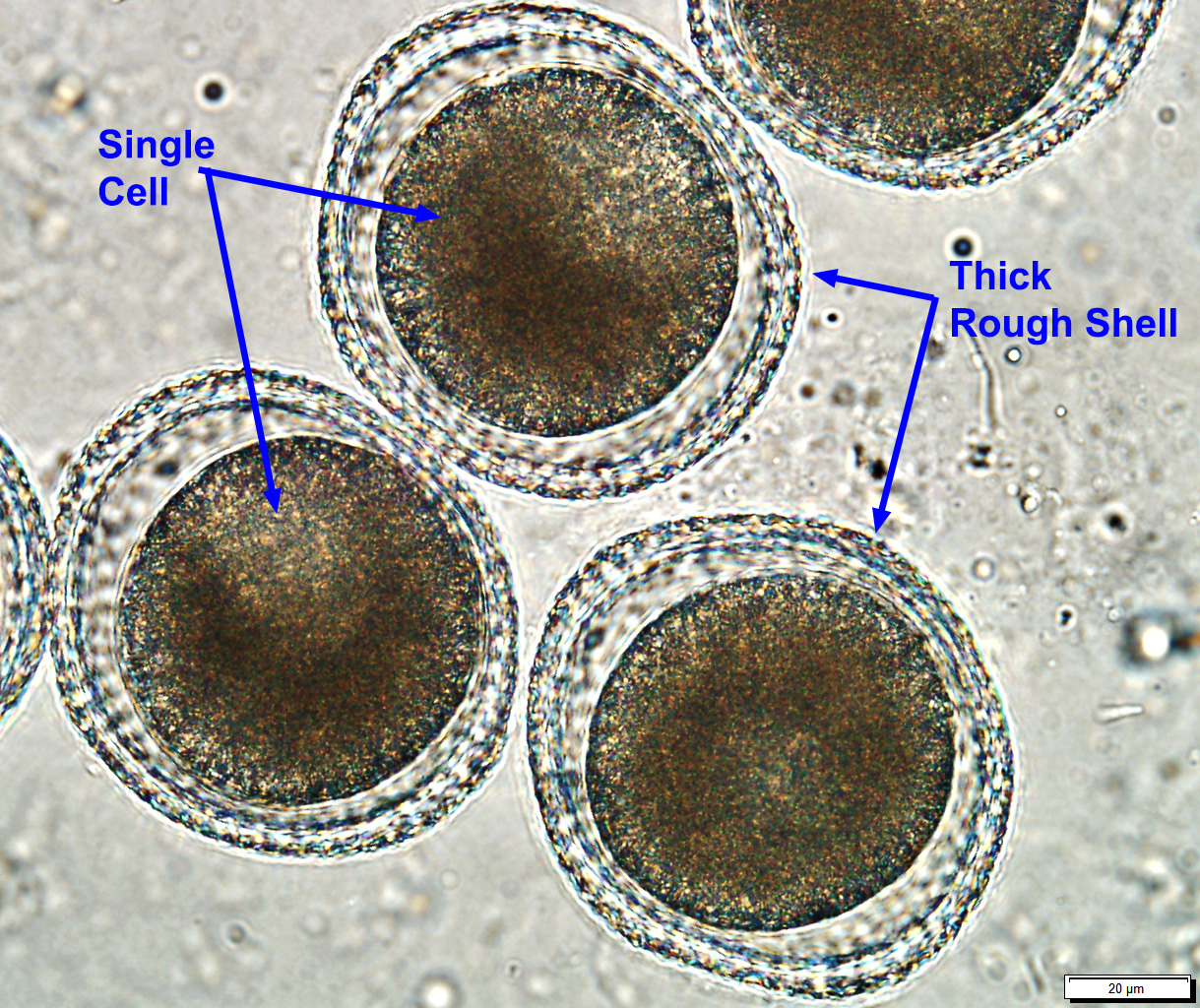

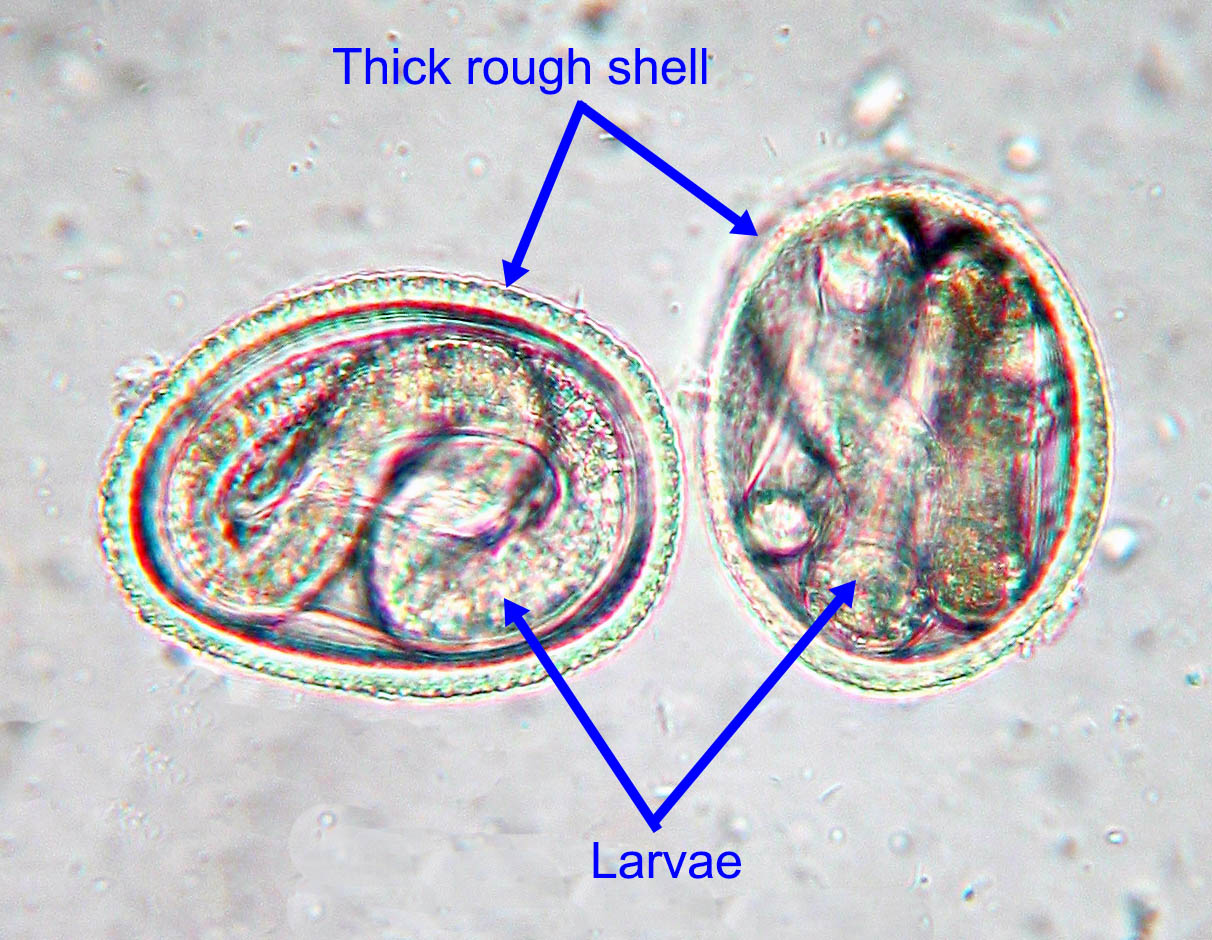

Eggs measure approximately 65 by 75 µm, and are sub-spherical with a thick, rough shell (“golf ball” appearance). Each egg contains one or two cells when freshly passed. The eggs are slightly smaller than those of T. canis although definitive differentiation often relies on molecular methods.

Host range and geographic distribution

In Canada, Toxocara cati is the most common helminth parasite of cats. It was present in 17% of shelter cats in a recent national study, and in 24% of cats less than a year old. Prevalence in healthy, owned, adult cats is much lower (<5%).

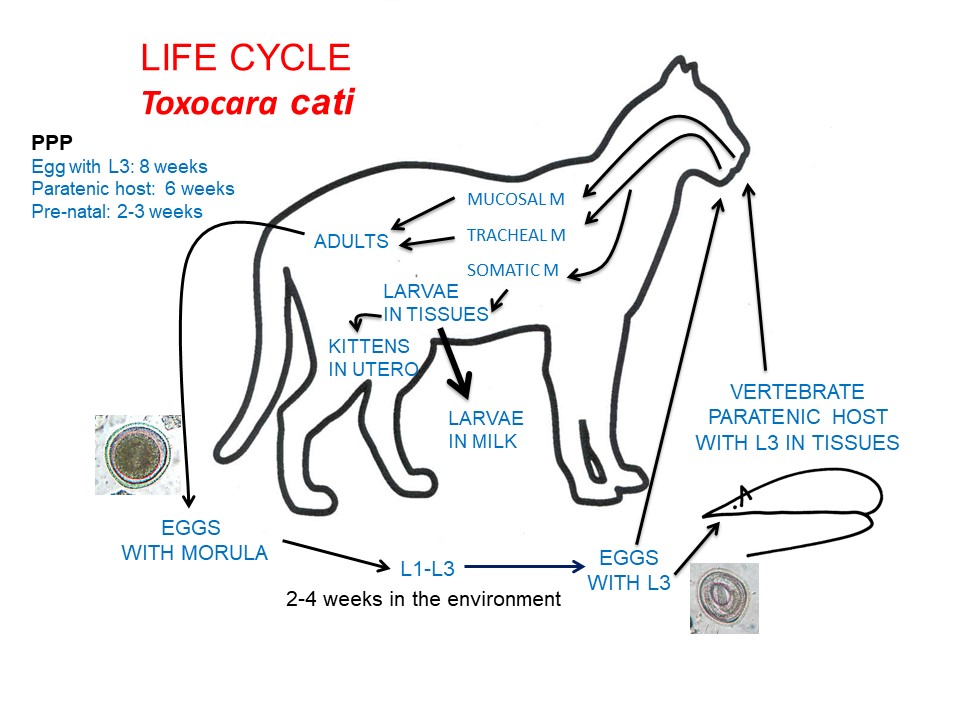

Life cycle

The life cycle of T. cati is believed to be similar to that for T. canis in dogs, with a few exceptions. Adult T. cati are located in the small intestine of the cat, and eggs leave the host in the feces. An infective third-stage larva develops in each egg after 2-4 weeks in ideal environmental conditions.

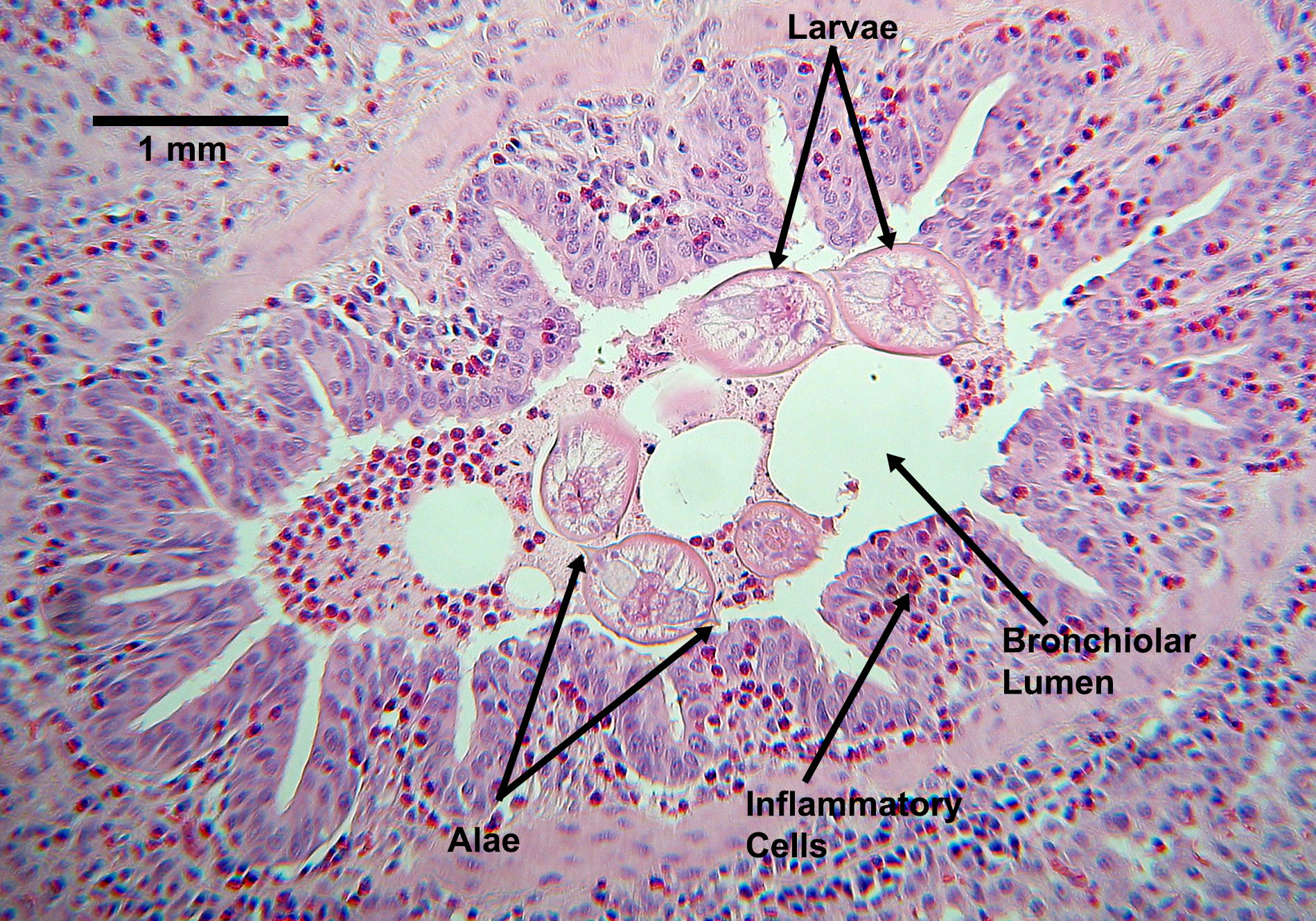

This development rate is temperature-dependent. After ingestion of an infective third-stage larva within the egg, larvae undergo a hepatotracheal migration and develop to adults in the intestine of younger cats, with a pre-patent period of 8 weeks . In lactating female cats, larvae of T. cati that have developed from eggs ingested during late gestation reach the mammary gland following somatic migration (GI tract to portal vessels to liver to heart to lungs to heart to mammary gland) and can be present in the milk throughout lactation. Trans-mammary transmission of larvae acquired by the mother in late pregnancy/early lactation is the primary route of infection for young kittens, who can have patent infections by 6 weeks of age (prenatal infection with somatic larvae does not occur). Because cats feed on small prey animals and usually bury their feces, T. cati infection is more commonly acquired by older kittens and adult cats from paratenic hosts (versus from ingesting L3 in eggs in the environment). These larvae undergo a simple mucosal migration and the prepatent period is 6 weeks.

Epidemiology

The major route of transmission for T. cati among kittens is ingestion of L3 in the milk from the mothers, and for older cats, through ingestion of L3 in the tissues of paratenic hosts. Like T. canis in pups, T. cati has a higher prevalence and intensity in kittens than in older cats. Parasite transmission through infective eggs in the environment is facilitated by eggs that are very resistant to adverse environmental conditions and can survive and remain infective for months or perhaps even years, especially in cool, damp conditions. Eggs are not immediately infective, but require several weeks in the environment to become infective for cats and paratenic hosts. Eggs can be inactivated by strong phenol, cresol, or bleach solutions, high temperatures (> 45 C), desiccation, and freezing at -20 C or below for weeks to months (eggs of T. cati may be more freeze tolerant than those of T. canis). Eggs are not inactivated by most common disinfectants, nor by fixation in formalin or ethanol. The use of litter boxes and the frequent burying of feces by cats probably help to reduce transmission.

Pathology and clinical signs

In young kittens, especially those infected from the milk, migrating larvae in the lungs may be associated with respiratory signs and, in untreated kittens, adult parasites in the GI system can be associated with suboptimal growth, and development, poor body condition (“pot-belly”), and diarrhoea, as well as possibly ”seizures”. The pathogenesis of these clinical signs is not fully understood. In older cats, neither adult parasites nor migrating larvae are commonly associated with clinical abnormalities.

Diagnosis

Treatment and control

Several products are approved in Canada to treat the life cycle stages of Toxocara cati in the GI system, and these products are used as part of an overall treatment and control program for GI nematodes. The treatment of young kittens is often less aggressive than that of young pups for T. canis, as the parasite is less zoonotic, and kittens do not start shedding eggs until 6 weeks of age. In the US, where feline hookworm is a local problem, starting the treatments at 2 weeks of age is still recommended.

Current best practice guidelines from the Canadian Parasitology Expert panel are that kittens should be treated at 2, 4, 6, and 8 weeks of age, then monthly until 6 months of age. One of the problems with starting the treatment schedule at two or three weeks of age is that many kittens do not have contact with a veterinarian until they are six or eight weeks old. Providing the drugs to breeders with encouragement towards good compliance would help address this problem.

For cats 6 months and older, recommendations differ depending on the risk profile of the cat and geographic location. In the USA, many parasitologists and veterinarians recommend monthly treatments year-round for the life of the cat. This schedule is thought to increase compliance and also coincide with monthly administration of heartworm preventatives. In most of Canada, where feline heartworm is exceedingly rare, a risk based approach is recommended. Cats which are free-ranging, known hunters, or are fed raw meat diets, frequently exposed to heavily contaminated environments (catteries, shelters), etc are considered high risk for exposure. Owners of service animals and animals in households that contain young children (under 3), pregnant, or immunocompromised people may have higher level of concern about parasitic zoonoses. In these cases (high risk cat and/or high risk household), test 1-2 times annually and treat at least 3-4 times a year. In older, low risk cats in low risk households (i.e. adult indoor cat on commercial diet), test and treat yearly. It is also appropriate to treat only if eggs are detected on annual fecal examination, especially if combined with coproantigen or coproPCR tests, which have high sensitivity.

Public health significance

References

Jenkins, E. 2020. Chapter 31: Toxocara spp. in dogs and cats in Canada. Advances in Parasitology 109:641-653. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.apar.2020.01.026

Villeneuve, L. Polley, E.J. Jenkins, J.M. Schurer, J. Gilleard, S. Kutz, G. Conboy, D. Benoit, W. Seewald, F. Gagné. 2015. Parasite prevalence in fecal samples from dogs and cats across the Canadian provinces. Parasites and Vectors 8:281 doi:10.1186/s13071-015-0870-x.Hoopes, J., J.E. Hill, L. Polley, C. Fernando, B. Wagner, J. Schurer, E. Jenkins. 2015. Enteric parasites of free-roaming, owned, and rural cats in prairie regions of Canada. Canadian Veterinary Journal 56(5): 495-501. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4399737/

Hoopes, J., L. Polley, B. Wagner, E.J. Jenkins. 2013. A retrospective investigation of feline gastrointestinal parasites in western Canada. Canadian Veterinary Journal 54:359-362

Epe C (2009) Intestinal nematodes: biology and control. Veterinary Clinics of North America Small Animal Practice 39: 1091-1107.