Toxoplasma gondii

Toxoplasma gondii is a zoonotic intracellular apicomplexan protozoan parasite of mammals and birds that occurs around the world, including in Canada.

Summary

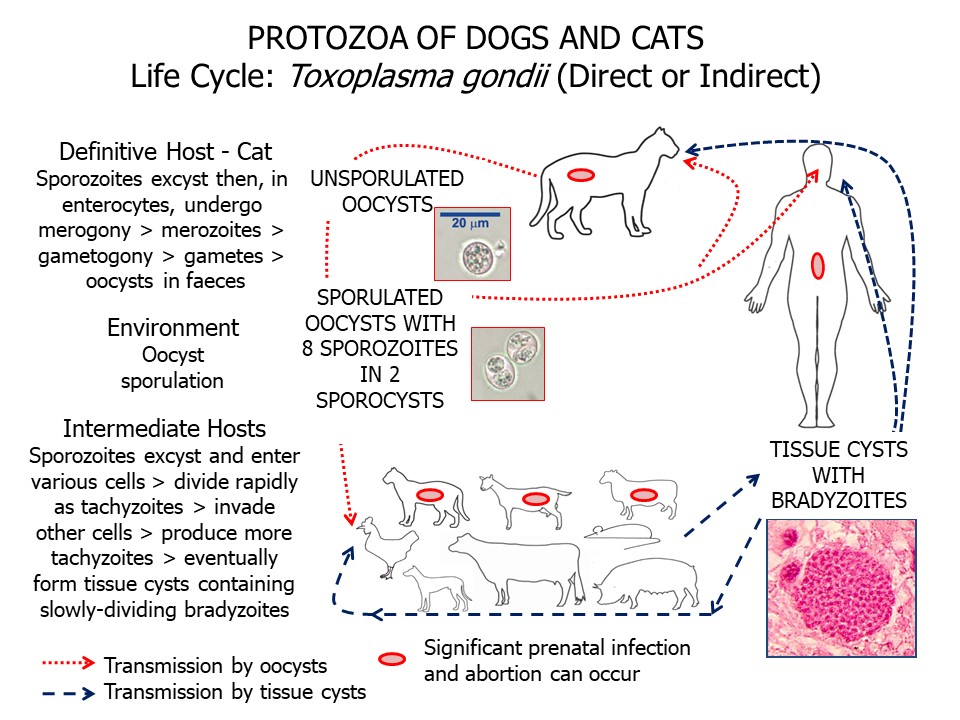

Toxoplasma gondii is a zoonotic intracellular apicomplexan protozoan parasite of mammals and birds that occurs around the world, including in Canada. Prevalence of infection varies with location, host species and, in many instances, host age. Infection with T. gondii is much more common than is clinical disease. The life cycle can be direct (among cats), but is usually indirect (between cats and a wide range of vertebrate intermediate hosts). The only definitive hosts are domestic and free-ranging felids in which the parasite undergoes asexual and then sexual reproduction in the enterocytes of the small intestine (similar to Eimeria), resulting in the production of unsporulated oocysts, which leave the host in the feces. In the environment (in a few days in ideal conditions) these oocysts sporulate and become infective - each contains four sporozoites in each of two sporocysts. If a naive felid ingests these sporulated oocysts, the parasite undergoes both extraintestinal and intestinal development . Thus T. gondii can complete its life cycle using only felids, although it is not optimal from the parasite’s viewpoint. If sporulated oocysts are ingested by a naive, vertebrate intermediate host, the sporozoites invade the intestinal wall, enter blood and lymph cells and, dividing rapidly as tachyzoites, spread throughout the body. Some of these tachyzoites come to rest in tissues, form a tissue cyst around them and divide slowly as bradyzoites. Tachyzoites and tissue cysts containing bradyzoites in mammalian and avian tissues, along with sporulated oocysts in the environment, are all infective for hosts. In some host species, notably people, sheep and cats, congenital (prenatal) infection of foetuses can also occur, with a risk of abortion, stillbirth and neonatal disease in the offspring. Diagnosis in pets and people relies primarily on serology. Treatment is useful only for acute systemic toxoplasmosis and to prevent congenital transmission or recrudescence of infections in immunocompromised pets and people. Control ultimately relies on preventing cats from consuming wildlife or uncooked meat, regular removal of cat feces and disposal away from water sources, and preventing cats from defecating in vegetable gardens or livestock feed. Raw meat should be cooked thoroughly or frozen solid for at least 3 days prior to human consumption or feeding to pets to inactivate tissue cysts of T. gondii.

Toxoplasma gondii is a major cause of abortion in sheep and goats and a threat to marsupials, New World primates and marine mammals. Toxoplasma gondii is also a significant human pathogen around the world. In the United States it is a common cause of ocular disease, and worldwide it is a problem in people with compromised immune systems. In people and in animals, recent evidence suggests that subclinical infections with T. gondii might influence mental development, as well as risk-taking behaviours.

NOTE: Identical information on T. gondii is included in the text for all the host species and for zoonoses. Information on the effects of the parasite on each host is included in the Pathology and Clinical Signs section.

Taxonomy

Phylum: Alveolata Subphylum: Apicomplexa

Class: Coccidea

Order: Eimeriida

Family: Sarcocystidae

Toxoplasma gondii, the cause of toxoplasmosis in people, animals and birds, is an apicomplexan protozoan related to the coccidians Neospora and Cystoisospora, with which it shares many biological features. Distinct strains, or clonal lineages, of T. gondii have been identified which differ in geographic distribution and some important biological features, including tendency to form cysts and pathogenicity in mice.

Note: Our understanding of the taxonomy of parasites is constantly evolving. The taxonomy described in wcvmlearnaboutparasites is based on Deplazes et al. eds. Parasitology in Veterinary Medicine, Wageningen Academic Publishers, 2016.

Morphology

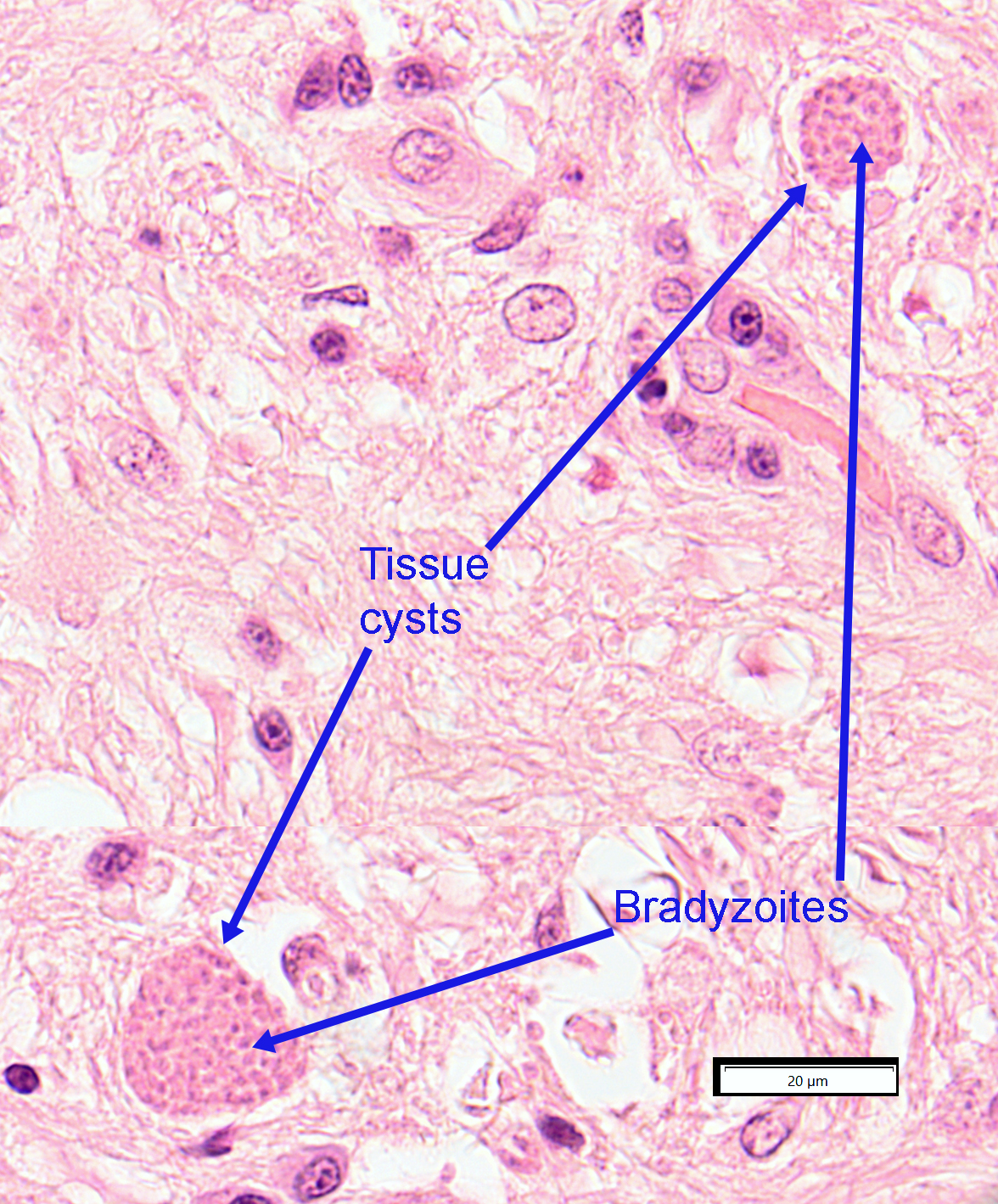

Toxoplasma gondii is largely an intracellular parasite. Several life cycle stages can be visualized using standard microscopy in various organs and tissues: a) tachyzoites (tissues and fluids of any host); b) tissue cysts (tissues of any host); c) bradyzoites within the tissue cysts (tissues of any host); d) meronts, gametocytes and gamonts (enterocytes of felids); and e) oocysts (feces of felids).

Tachyzoites of T. gondii are crescent-shaped, measuring approximately 6 µm by 2 µm, with a central nucleus and a pointed anterior and a blunt posterior end. Details of the internal structures are not visible by light microscopy. Tachyzoites are normally located within cells, but sometimes in histological sections they appear to be extracellular, and may appear singly or, less commonly, in small groups.

Tissue cysts of T. gondii occur in a variety of organs and tissues, particularly the central nervous system and skeletal musculature, and are round to oval, with a greater dimension of up to 100 µm. The cyst wall is thin, measuring less than 0.5 µm thick. Tissue cysts of T. gondii can contain from a few to hundreds of bradyzoites. The basic structure of tissue cysts, including the bradyzoites, can be seen by light microscopy.

Bradyzoites of T. gondii occur within the tissue cysts. They are very similar in structure to tachyzoites, except that the nucleus is usually posterior. Details of the internal structures are not visible by light microscopy.

Meronts, gametocytes and gamonts of T. gondii in the enterocytes of cats are basically similar in structure to the same stages in Cystoisospora.

Oocysts of T. gondii are approximately spherical, measure 10 to 12 µm in diameter, and have a smooth, thin shell. When passed in feces they contain one or two cells, and when sporulated (a process that takes a few days under ideal conditions), each contains two sporocysts, each with four sporozoites. Oocysts of T. gondii are very difficult to distinguish microscopically from those of the Hammondia and Cystoisospora species infecting cats, requiring PCR for definitive diagnosis.

Host range and geographic distribution

Surveys and case reports from around the world have demonstrated serological and other evidence of Toxoplasma gondii infection in a wide range of mammals and birds. In some regions of Canada, Toxoplasma is a significant problem in sheep as a cause of abortion, and across the country the parasite is an occasional cause of disease in other host species, including people.

Life cycle - direct or congenital

Toxoplasma gondii requires felids (domestic or free-ranging) as definitive hosts. Only in these hosts can the parasite undergo asexual (merogony) and then sexual (gametogony) reproduction in the epithelial cells of the small intestine. This phase of the life cycle is very similar to that of Cystoisospora. Sexual reproduction results in oocysts, which pass in the feces. Oocyst production is higher in young kittens than in adult cats, and following the ingestion of tissue cysts rather than oocysts. Ingestion of tissue cysts by felids is twice as likely to result in oocyst production than is tachyzoite or oocyst ingestion. Also, most cats will excrete oocysts only for a few weeks following infection, and only when first infected. A few cats, however, will continue to produce low numbers of oocysts; it is not clear if this is due to reinfection or recrudescence. To become infective for another host, these oocysts must sporulate - four sporozoites develop within each of two sporocysts within each oocyst. Under ideal conditions, sporulation takes a few days.

If a felid host ingests sporulated oocysts, a small proportion of the ingested sporozoites undergo development in the enterocytes of the small intestine, as described above, while the majority undergo extraintestinal development, as occurs in the intermediate host. When unsporulated oocysts are ingested by a naive vertebrate intermediate host, the sporozoites enter the intestinal wall, then blood and lymph cells, begin to divide rapidly as tachyzoites, and are distributed throughout the body. Once in the tissues, tachyzoite division slows and they give rise to tissue cysts containing bradyzoites, which divide slowly. Tissue cysts are most commonly located in the central nervous system, including the eyes, and in skeletal and cardiac muscle. These tissue cysts can persist in an animal or person for years, often without adverse effect, and eventually they die. Under some circumstances, however, for example immunosuppression, parasite division in the cysts can be accelerated and the resulting tachyzoites released and distributed throughout the body. In cats, and in some other hosts including sheep and people, Toxoplasma can be transmitted from a female to her foetuses prenatally. The parasite has also been transmitted between people by blood transfusion or organ transplantation.

Infections with Toxoplasma can occur following the ingestion by definitive or intermediate hosts of tachyzoites (less common), tissue cysts with bradyzoites, or sporulated oocysts. In the definitive hosts, the pre-patent period for T. gondii varies depending on the life cycle stage ingested: 3 to 10 days for bradyzoites, and approximately three weeks for oocysts and tachyzoites. Toxoplasma is, so far, the only coccidian parasite that can transmit horizontally among intermediate hosts by carnivory - any naive vertebrate that ingests a tissue cyst in prey can itself become infected.

Epidemiology

The three major means of T. gondii transmission are: a) consumption of sporulated oocysts in the feces of cats, or in the environment (for example, drinking water and contaminated vegetation); b) consumption of bradyzoites in tissue cysts (and possibly tachyzoites, for example in unpasteurized milk from goats); and c) congenital infection by tachyzoites crossing the placenta in a pregnant female infected for the first time in pregnancy. Based on the levels of seroprevalence reported for people and for animals and birds, Toxoplasma can utilize a variety of transmission routes and is very successful at maintaining itself around the world.

Dietary preferences influence the epidemiology of Toxoplasma. For example, herbivores most likely acquire the infection following the ingestion of oocysts from the environment, whereas carnivores could also become infected by ingesting tissue cysts in meat. In a recent study in the United States, significant risk factors for human exposure to T. gondii were identified as eating raw or undercooked foods (raw ground beef, rare lamb, locally produced cured, dried or smoked meat, unpasteurized goat milk, or raw oysters, clams or mussels - which can concentrate oocysts during filter feeding), and having three or more kittens (< 1 year old). Recent outbreaks of water-borne toxoplasmosis in people suggest contamination of water reservoirs with feces of domestic and free-ranging felids. The oocysts of T. gondii can survive for long periods (up to years) in supportive environmental conditions, including in freshwater, sea water, and cool, moist soil.

Pathology and clinical signs

Cats

In Canada a national serological survey in 2002 detected exposure to Toxoplasma in 19% of 287 cats taken to veterinary clinics. Many people, animals and birds infected with T. gondii show few or no detectable clinical signs. The clinical effects of T. gondii reflect the location of the lesions. Clinical toxoplasmosis is more severe in congenitally (pre-natally) infected kittens than in older cats. In cats of all ages the lungs are the most often affected, leading to pneumonia, but damage to other organs and tissues can also result in clinical disease, and sometimes the infection is generalized.

Dogs

Prevalence in dogs in Canada is not well described, but a few studies (primarily in remote communities in western Canada) show seroprevalence from 20-50%. Although Toxoplasma occurs in dogs in Canada, other than a few case reports of eye involvement, it is rarely associated with disease. Evidence from other parts of the world indicate that lungs, liver and central nervous system are most often affected in congenitally infected pups, and pregnant females exposed for the first time may abort.

Cattle

Clinical disease unequivocally associated with Toxoplasma has not been reported in cattle, and sub-clinical infections seem to be rare around the world, including in Canada. In general it is believed that meat from cattle is an unlikely source of the parasite for people, at least in more developed regions of the world, but uncertainty remains.

Sheep and Goats

In Canada and around the world Toxoplasma is a major problem in sheep, and to a lesser extent goats, as a cause of abortion and neo-natal disease. Ewes and nannies that are infected for the first time during pregnancy can pass the parasite pre-natally to their offspring which, depending on the stage of pregnancy when infection occurs, could abort, be stillborn or develop disease in the neonatal period, Because of the development of immunity, a ewe that aborts is unlikely to do so again in subsequent pregnancies. Clinical toxoplasmosis is thought not to occur in sheep, but there are reports of multi-systemic disease in goats.

Horses

Toxoplasma gondii does not establish well in horses so sub-clinical and clinical infections are likely very rare.

Pigs

Serological surveys in many parts of the world have demonstrated that Toxoplasma infection is not uncommon in pigs. In Canada, Toxoplasma is very rare in commercial pigs due to widespread use of intensive management systems. Backyard or pasture pigs have significantly higher risk of exposure due to consumption of oocysts on pasture or in water, or from preying on or scavenging rodents. Pigs should never be fed uncooked or unprocessed meat or organs. Where T. gondii does occur in pigs, undercooked porkcan be an important source of human infections. Clinical toxoplasmosis appears to be very rare in pigs.

Poultry

Serological data indicate that T. gondii is not uncommon in poultry in many parts of the world, particularly in birds in extensive management systems, but the situation in Canada is not known in detail. Reports of clinical toxoplasmosis in poultry are very rare, and indicate that the nervous system is the most likely target. The transmission of T. gondii to people via eggs is very unlikely.

Other Animal and Bird Hosts

Around the world infection with Toxoplasma, and less commonly clinical disease associated with the parasite, have been detected in a wide variety of mammals and birds, including pocket pets, caged and free-ranging birds, game animals, marsupials, New World primates and marine mammals. In Canada, prevalence in wild carnivores can be very high (>70%). Human cases of toxoplasmosis in North America have been linked to consumption of undercooked venison.

People

Toxoplasma gondii infection in people can be acquired pre-natally from the mother (congenital infection) , or post-natally by ingestion of sporulated oocysts in felid feces, water or unwashed producet, or by ingestion of tissue cysts containing bradyzoites or, less commonly, tachyzoites in animal tissues. Infection with the parasite is not uncommon in people around the world, including Canada, but clinical disease is rare among those with competent immune systems. Congenital infections can result in abortion, stillbirth or lesions in the central nervous system, especially the eyes, depending on the timing in gestation, the infective dose, and the route of exposure . Congenital infections in people can sometimes result in severe clinical disease, and clinical signs might not appear until weeks or months after birth. Congenital toxoplasmosis can also result in learning difficulties for children. With acquired infections in immuno-competent people, Toxoplasma usually causes only a transient flu-like illness with fever, malaise and enlarged lymph nodes. In people with compromised immunity, Toxoplasma is a more serious problem which most often affects the central nervous system. Toxoplasma encephalitis was a major cause of disease and death in people with HIV/AIDS, but its role has lessened following the introduction of anti-retroviral drugs. While Toxoplasma gondii infection is generally considered serious only in pregnant women or immunocompromised people, chronic infection has also been linked to schizophrenia, suicide, and risk-taking behaviour, raising the possiblity that asymptomatic infections in immunocompetent people may not be as benign as once thought.

Diagnosis

In felids with enteric infections, detection of T. gondii oocysts in feces is generally possible only within the two to three week patent period following acute infections. The oocysts are unsporulated, sub-spherical, measure approximately 12µm by 10µm, and cannot be easily distinguished microscopically from those of non-pathogenic Hammondia hammondi or Cystoisospora.

In both animals and people, there are multiple serological tests for antibodies to T. gondii, including modified agglutination tests (MAT), direct agglutination tests (DAT), ELISA, and IFAT. Some of these require species-specific conjugates, which may not be available; however, there is a commercially available ELISA that can be used in all mammalian species.

At post-mortem, detection of tissue cysts with bradyzoites, or tachyzoites, or of “typical” pathological changes, can help to establish the diagnosis. PCR and immunohistochemistry can differentiate among other tissue cyst forming protozoans, such as Neospora or Sarcocystis. Bioassay (feeding tissues tocats or mice) is the only way to demonstrate viable organisms, but it is increasingly unacceptable for simple diagnosis.

Treatment and control

There are no products approved in Canada for the treatment of Toxoplasma gondii infection in animals. In dogs and cats, treatments include clindamycin, pyrimethamine, and trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole Treatment is useful only for acute systemic toxoplasmosis and to prevent congenital transmission or recrudescence of infections in immunocompromised pets and people. Prior to starting immunosuppressive therapy, it is worth determining the serostatus of the pet, because previously latent T. gondii infection may be re-activated. Treatment will not inactivate tissue cysts.

A vaccine that prevents abortion in sheep (Toxovax®) is commercially available in New Zealand and in some European countries. It is based on live attenuated organisms. A vaccine has also been developed and validated to reduce oocyst shedding in cats, but the logistics of producing the live, attenuated bradyzoites make the product commercially unrewarding. Vaccines to prevent the establishment of T. gondii infection in people and in meat animals have the potential to be helpful in minimizing the prevalence and severity of human infection, but are not yet available.

The control of T. gondii in its various hosts depends on interrupting the transmission cycle primarily by preventing access to sporulated oocysts and tissue cysts. Owners can reduce risk of exposure of their pets (and themselves) to T. gondii by keeping cats indoors and feeding pets only commercial or cooked diets (not microwaving, which does not heat the meat uniformly). If raw meat is fed to cats or dogs, it should be frozen solid for at least 3 days to inactivate tissue cysts of T. gondii. Daily cleaning of the litter box is helpful, as it removes oocysts from the environment before they can sporulate. Pregnant women should avoid contact with litter boxes or gardens that could be contaminated with cat feces. People should also avoid consumption of unfiltered surface water and unwashed produce. Cats should not be allowed to fecally contaminate vegetable gardens or livestock feed or water, and all pasture-raised sheep, goats, and swine should be considered potentially exposed to T. gondii.Public health significance

Toxoplasma gondii is a common parasite in people worldwide, with an estimated global seroprevalence of ~30%. In Canada, the prevalence in the general population is probably closer to 10-15%, with higher seroexposure in Inuit communities in some regions of the Arctic (30-60%). The three major routes of transmission of T. gondii to people are: a) consumption of tissue cysts in undercooked meat (and possibly tachyzoites in unpasteurized milk or cheese from goats); b) accidental consumption of oocysts in unfiltered surface water or unwashed produce ; and c) congenital infection in fetuses of women infected for the first time in pregnancy. People can also acquire T. gondii from blood transfusion or organ transplant. Approximately 50% of human infections with T. gondii are thought to be food-borne, through consumption of tissue cysts in meat, although there is no information about the proportion of infections acquired through consumption of unwashed produce.

In 1994-95 there was a major outbreak of human toxoplasmosis in the Victoria (BC) area associated with a municipal water supply from one particular reservoir contaminated with faeces from cougars and domestic and feral cats with evidence of T. gondii infection. Estimates suggest that several thousand people may have been infected. Eye lesions were particularly common, and several pregnant women were at sufficient risk for abortion to be recommended. It is possible that this outbreak was caused by a particularly virulent genotype of the parasite. Other waterborne outbreaks have subsequently been identified in Brazil.

Meats in Canada with a relatively high risk of T. gondii infection include wildlife, especially bears, lynx, and other carnivores, as well as lamb and mutton. In the US, pigs are the major domestic animal meat source for human T. gondii infection but the parasite appears to be rare in intensively managed pigs in Canada.

References

Scallan E et al. (2011) Foodborne illness acquired in the United States - major pathogens. Emerging Infectious Diseases 17: 7-15.

Dubey JP et al. (2009) Toxoplasmosis and other intestinal coccidial infections in dogs and cats. Veterinary Clinics of North America Small Animal Practice 39: 1009-1034.

Sibley LD et al. (2009) Genetic diversity of Toxoplasma gondii in animals and humans. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London Series B Biological Sciences 364: 2749-2761.

Dubey JP et al. (2008) Toxoplasma gondii infection in people and animals in the United States. International Journal for Parasitology 38: 1257-1278.

Hill DE et al. (2005) Biology and epidemiology of Toxoplasma gondii in man and animals. Animal Health Research Reviews 6: 41-61