Trichuris vulpis

Adults of the nematode Trichuris vulpis live in the large intestine of dogs and rarely cats. The life cycle is direct and the infective stage is a larvated egg.

Summary

Adults of the nematode Trichuris vulpis (whipworm) live in the large intestine of dogs and wild canids. Cats have their own species, which appear to be extremely rare. The life cycle is direct and the infective stage is a larvated egg containing, unusually, a first-stage larva. Larvae develop only under high humidity conditions. Dogs and cats infected with T. vulpis may show minimal or no clinical signs, but in some cases there can be recurrent mucoid diarrhea and dysentery. Diagnosis is based on clinical signs (if present) and detection of characteristic eggs in a high specific gravity flotation solution, +/- coproantigen/PCR. Many recent products have labels for T. vulpis, but control may require multiple treatments as well as environmental decontamination, as eggs can survive for long periods. Trichuris vulpis is usually not considered to be a significant zoonosis, although human cases have been reported.

Taxonomy

Phylum: Nematoda

Class: Adenophorea (Aphasmidia)

Order: Enoplida

Superfamily: Trichinelloidea

Family Trichuridae

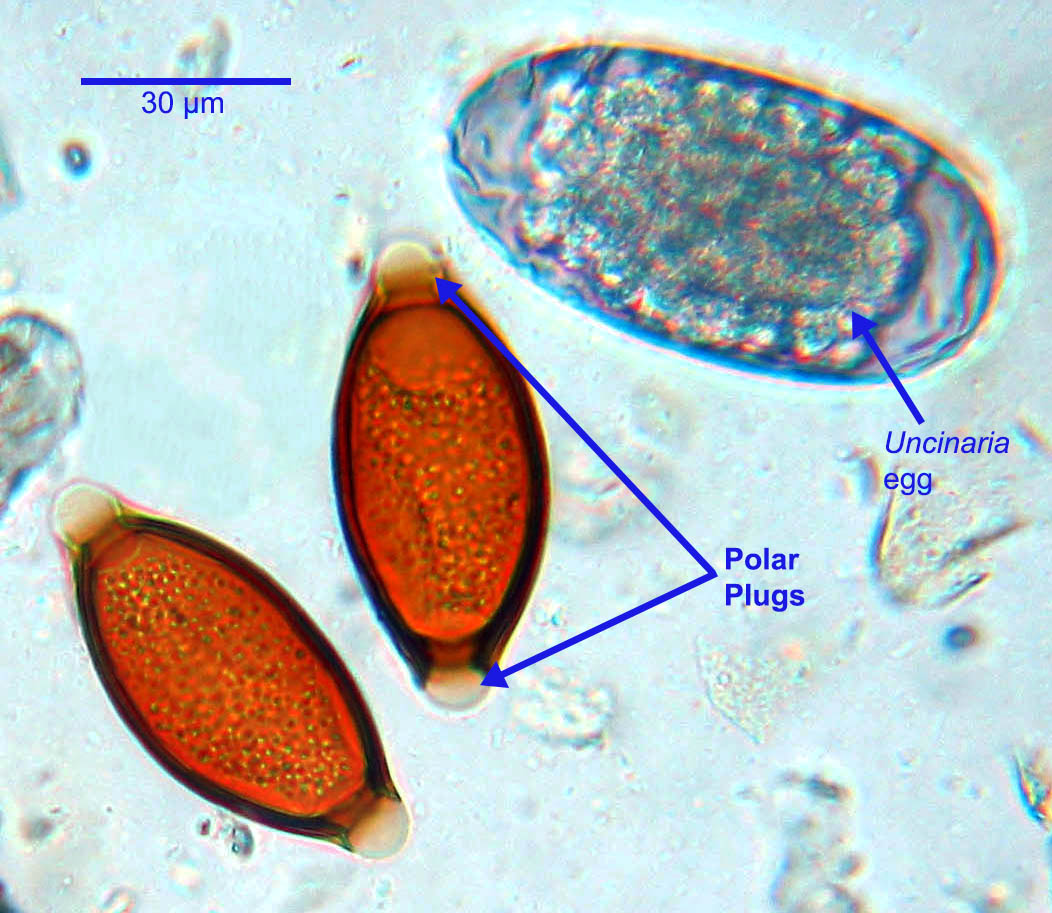

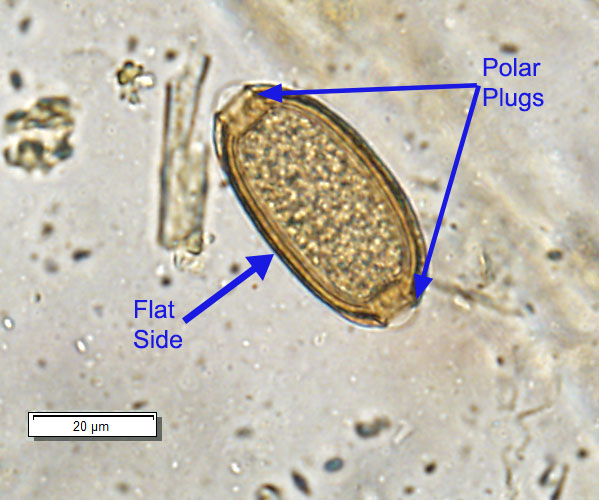

Trichurs vulpis, the whipworm of dogs, and the other species of Trichuris infecting domestic and free-ranging mammals, is one of a few parasites of veterinary importance in the Class Adenophorea (most are in Orders in the Class Secernentea). Others within the Order Enoplida include the genera Trichinella, Capillaria, and Dioctophyme. For parasites in this order, eggs typically have “plugs” at both poles. All species of Trichuris have a similar structure and life cycle.

Note: Our understanding of the taxonomy of parasites is constantly evolving. The taxonomy described in wcvmlearnaboutparasites is based on Deplazes et al. eds. Parasitology in Veterinary Medicine, Wageningen Academic Publishers, 2016

Morphology

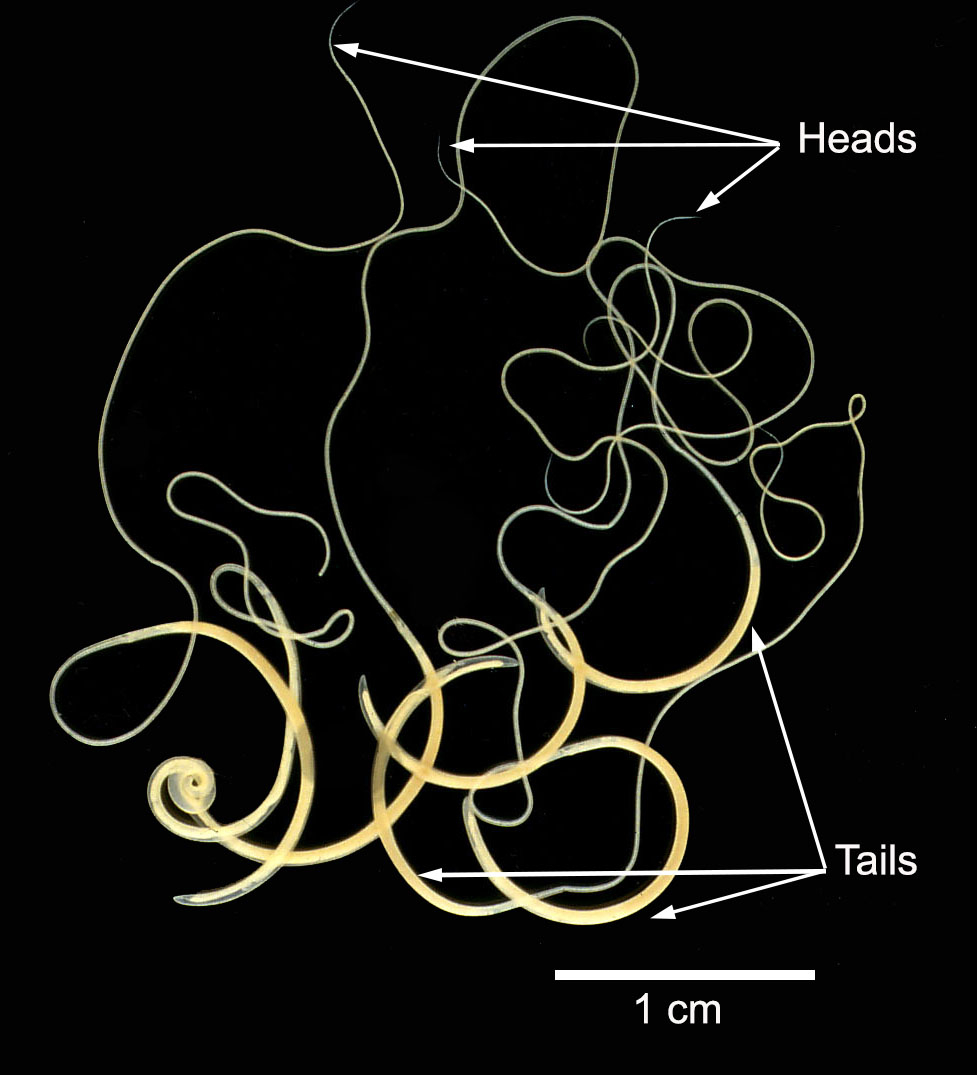

Adult T. vulpis are up to approximately 75 mm in length and have a characteristic “whip” shape, slender anteriorly and broader posteriorly.

Eggs of T. vulpis measure approximately 70 to 90 µm by 30 to 40 µm and, because of the polar plug at each end, are commonly described as “lemon” shaped.

Host range and geographic distribution

Cats have their own species of Trichuris, including Trichuris serrata, but all are rare in cats.

Life cycle - direct

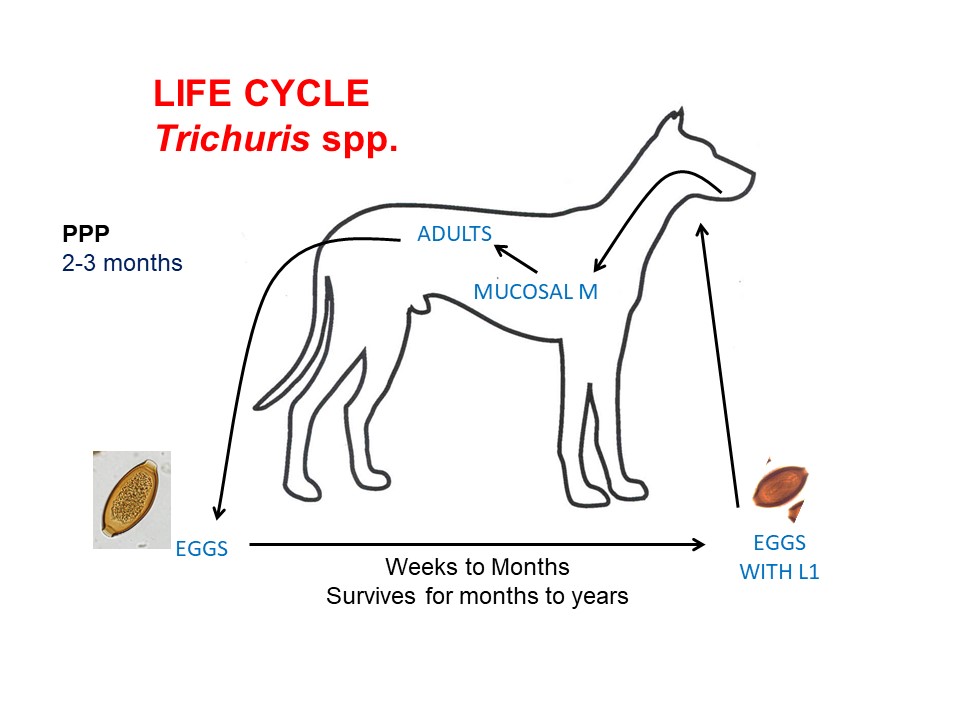

Adult T. vulpis live in the caecum, with their anterior ends “threaded” into the mucosa. Eggs are passed in the feces and larvate in the environment in 10 days under optimal conditions (warm and wet). Unusually, first stage larvae are the infective stage. Infection follows ingestion of the larvated eggs (containing L1) which hatch in the intestinal lumen, releasing larvae that undergo a mucosal migration and 4 moults to become adults. The pre-patent period is relatively long, approximately three months.

Pathology and clinical signs

Clinical signs of whipworm infection in dogs are associated primarily with the adult parasites and their invasion of the mucosa of the large intestine. Typical signs include diarrhea, often with blood and mucus, which may appear for a few days and then apparently resolve only to recur later. In dogs, infection with T. vulpis is more common than is disease.

Diagnosis

Epidemiology

Treatment and control

Several products available in Canada are effective against the stages of Trichuris vulpis in the GI lumen of dogs. Trichuris vulpis is not susceptible to some of the older anti-parasitics (pyrantel), but benzimidazoles and most of the newer macrocyclic lactones are very effective. There are no products approved in Canada for Trichuris infection in cats, which either does not occur or is very rare.

Public health significance

References

Villeneuve, L. Polley, E.J. Jenkins, J.M. Schurer, J. Gilleard, S. Kutz, G. Conboy, D. Benoit, W. Seewald, F. Gagné. 2015. Parasite prevalence in fecal samples from dogs and cats across the Canadian provinces. Parasites and Vectors 8:281 doi:10.1186/s13071-015-0870-x.