Uncinaria stenocephala

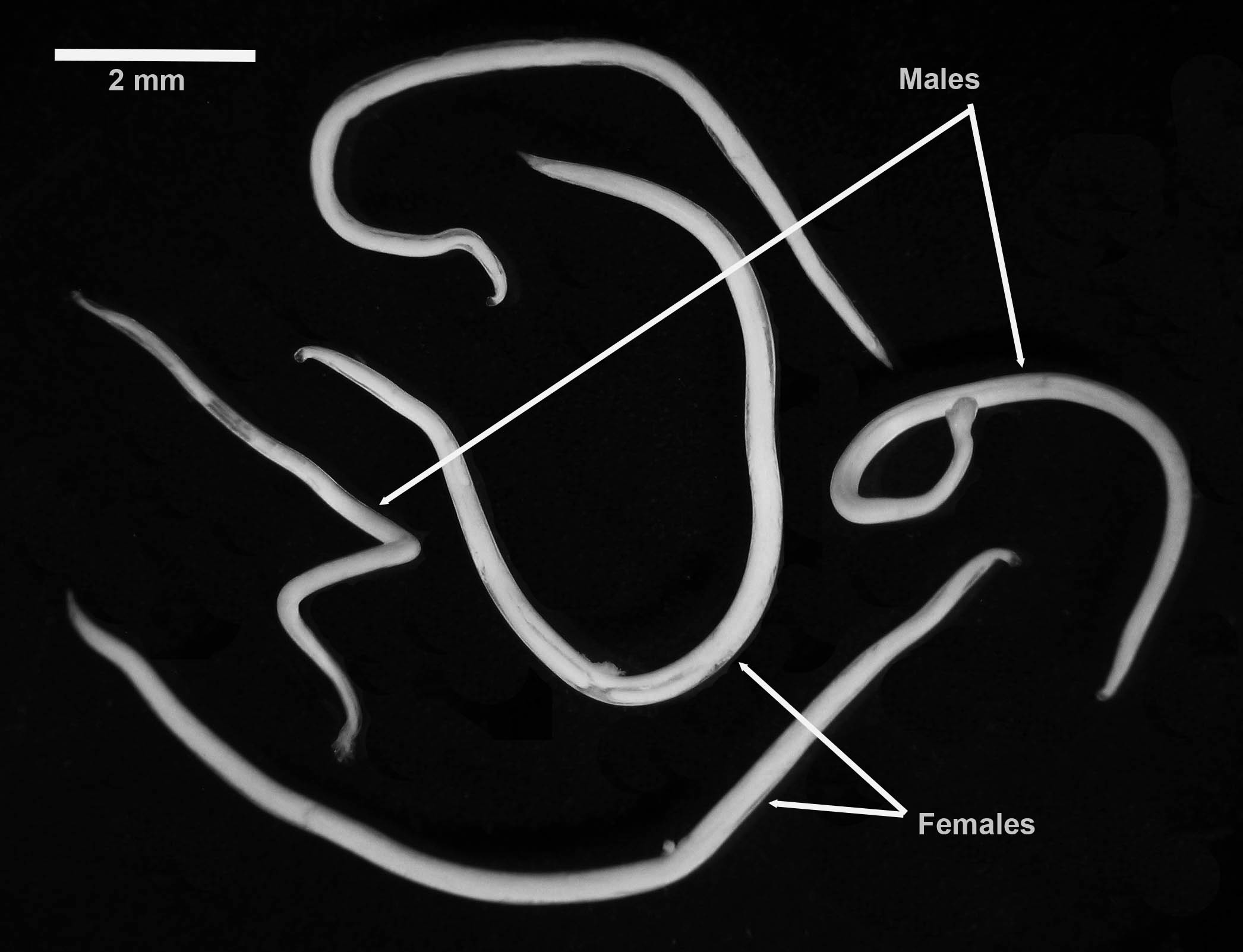

Adults of the nematode Uncinaria stenocephala live in the small intestine of dogs.

Summary

Taxonomy

Phylum: Nematoda

Class: Secernent

Order: Strongylida

Superfamily: Ancylostomatoidea

Family: Ancylostomatidae

Uncinaria stenocephala is the northern hookworm of dogs. It is related to the other hookworms of dogs (A. caninum, A. braziliense and A. ceylanicum), and to the hookworms of cats (A. tubaeforme and A. ceylanicum) and of people (A. duodenale and Necator americanus). The adult parasites and the eggs of these various hookworm species are morphologically similar, and the life cycles and pathology share many features. Some species of hookworm are able to infect several species of host, including people.

Morphology

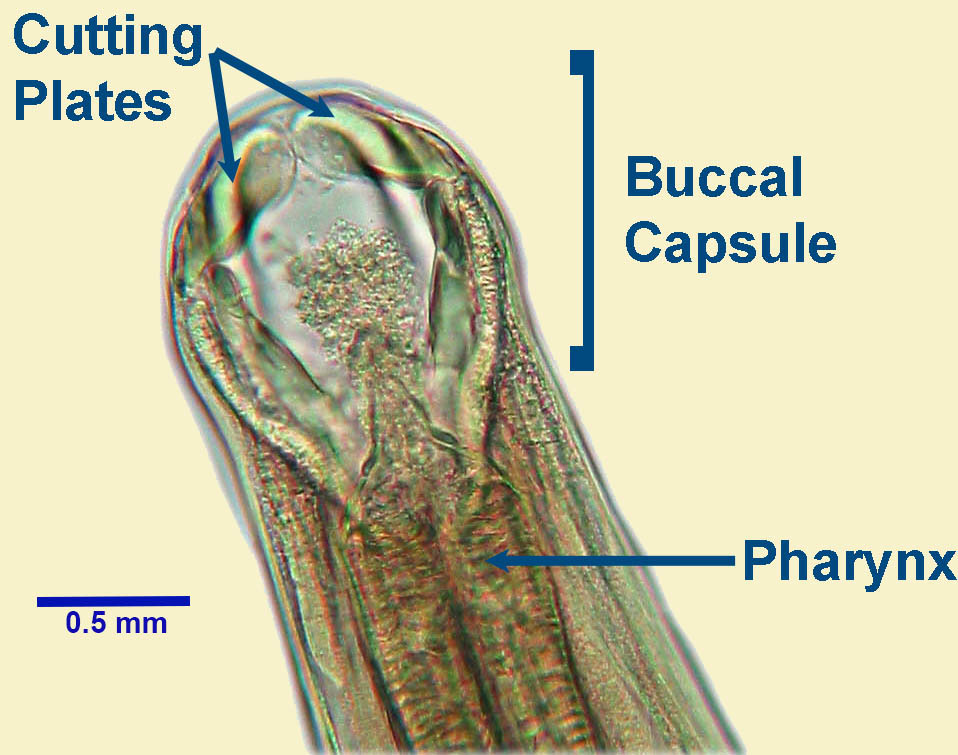

Adult U. stenocephala are up to approximately 15 mm in length and have a prominent buccal capsule, the opening into which has two cutting plates , one on each side of its ventral aspect. The exact structure of the buccal capsule is important in distinguishing between the various hookworm species.

Eggs measure approximately 65 to 80 µm by 40 to 50 µm, and are oval with a thin, smooth shell. When freshly passed, each egg contains a few cells grouped together - a "morula". Eggs of U. stenocephala are slightly larger than those of A. canium, and this is the basis for differentiation of the two parasites on fecal examinations.

Host range and geographic distribution

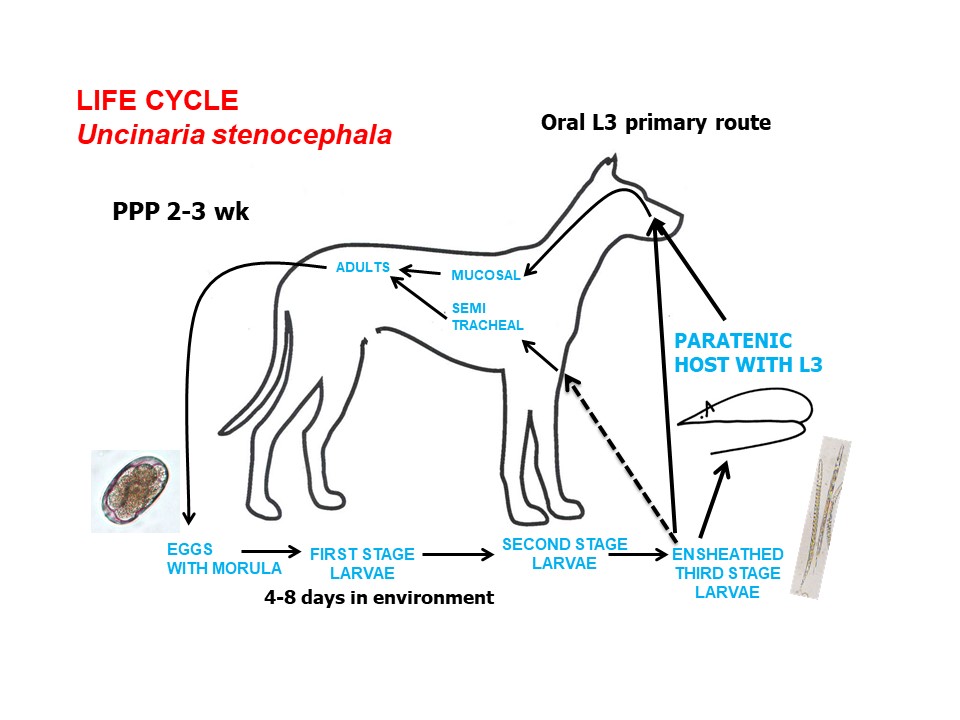

Life cycle - direct

Epidemiology

Environmental stages of hookworms are not particularly robust (compared to other parasites) and do best in warm, moist environmental conditions that support the survival and rapid development of the infective larvae. Sub-optimal hygiene also favours the parasite by exposing susceptible dogs to these larvae. For animals in kennels or shelters, where host density enhances opportunities for transmission, effective treatments and maintaining a clean environment are key elements of all control programs.

Pathology and clinical signs

Diagnosis

Treatment and control

Several products are marketed in Canada that are effective against the stages of Uncinaria stenocephala in the GI lumen including benzimidazoles and macrocyclic lactones. Because of the low pathogenicity of U. stenocephala, however, specific treatment or control measures are rarely recommended. These hookworms can be problematic in kennels and shelters (largely due to rapid re-infection from the environment), and control should include enhanced environmental hygiene and improved management, as well as targeted treatment and repeat testing to monitor treatment efficacy. Anthelmintic resistance, which is an increasing problem with Ancylostoma caninum, has not yet been described for Uncinaria stenocephala.

Public health significance

References

Chu, S., Myers, S. L., Wagner, B., & Snead, E. C. (2013). Hookworm dermatitis due to Uncinaria stenocephala in a dog from Saskatchewan. Canadian veterinary journal 54(8), 743–747.