Alaria species

Alaria species are intestinal trematodes of domestic dogs and occasionally cats, and of free-ranging canids and felids.

Summary

Alaria species are intestinal trematodes of domestic dogs and occasionally cats, and of free-ranging canids and felids.

In Canada the species in dogs occur primarily in northern regions, and the species in cats (Alaria marcianae) is thought to be very uncommon. The life cycles of Alaria species are indirect, involving a snail first intermediate host, a frog second intermediate host, and sometimes small mammal paratenic hosts.

Following the ingestion of the infective metacercariae (known as mesocercariae for Alaria), the immature flukes follow a modified tracheal migration in which they penetrate the gut wall and the diaphragm to enter the lungs. whereupon they are coughed up, swallowed, and develop to adults in the intestine.

If a female cat is infected with A. marcianae while lactating the immature flukes can migrate to the mammary glands and infect suckling kittens via the milk.

In dogs and cats, Alaria is generally thought to be non-pathogenic. People can acquire Alaria, usually following ingestion of infected frogs, and human infections have been associated with ocular disease and rarely death resulting from damage to the lungs caused by the migrating immature flukes. A human fatality caused by Alaria has been reported from Ontario.

Morphology

Adult Alaria are up to 6 mm in length and fleshy. Their most obvious characteristics are two wing-like alae that arise dorsally and envelop the anterior end of the fluke (although they are commonly called legs). Sometimes the oral and perhaps the mid-body ventral suckers are visible to the naked eye, but even in fixed and stained specimens internal structures are not usually visible.

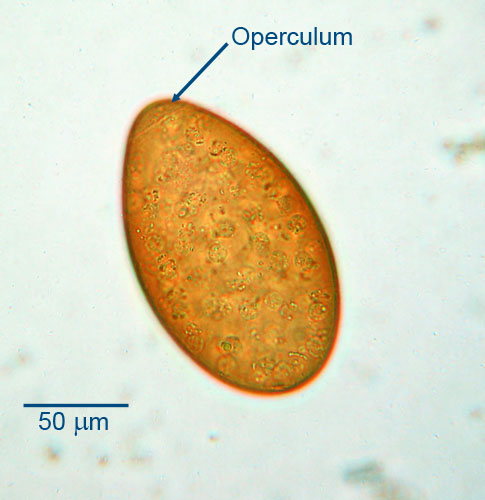

The eggs of Alaria measure approximately 100 to 130 µm by 62 to 68 µm and are characteristically golden yellow-brown in colour, with a thin, smooth shell and an operculum (lid) at one end. The larval stage within the egg is not usually visible.

Taxonomy

Phylum: Platyhelminthes

Class: Trematoda

Subclass: Digenea

Order: Strigeatidaiformes

Family: Diplostomatidae

Alaria is the only fluke within the Family Diplostomidae that is significant in veterinary medicine. In common with other digenean flukes, Alaria has an indirect life cycle involving a molluscan intermediate host.

The exact identity of the one or more species of Alaria infecting dogs in western Canada is not known, although A. arisemoides and A. americana have been reported in wild canids in Canada. Alaria marcianae occurs in domestic cats and other carnivores in the United States and elsewhere, but has not been reported from cats in Canada.

Note: Our understanding of the taxonomy parasites is constantly evolving. The taxonomy described in wcvmlearnaboutparasites is based on Deplazes et al. eds. Parasitology in Veterinary Medicine, Wageningen Academic Publishers, 2016.

Host range and geographic distribution

Flukes of the genus Alaria are common in a range of carnivores in North America and elsewhere. In Canada, the parasite is most commonly seen in dogs, especially those from northern areas.

Alaria marcianae occurs in domestic cats and other carnivores in the US and elsewhere, but has not been reported from cats in Canada. The extent of transmission of Alaria species between domestic and free-ranging hosts in Canada is not known. Alaria is an occasional zoonosis, including in Canada although people are considered to be accidental hosts in which the parasite does not fully develop.

Life cycle -- indirect

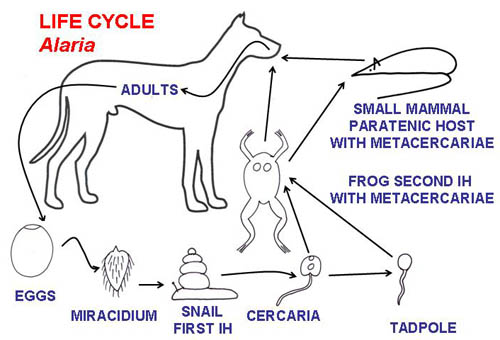

Adult Alaria are located in the small intestine of the definitive host and, like most other flukes, are hermaphrodite, and eggs, produced by sexual reproduction, are shed in the feces. In an aquatic environment, a miracidium (first larval stage) develops within each egg and, following opening of the operculum, is released into the water.

For the life cycle to continue, the miracidium must penetrate the skin of a suitable snail first intermediate host, in which a sporocyst, then rediae, then many cercariae develop via assexual reproduction. When a cercaria leaves the snail, for the life cycle to continue it must penetrate the skin of a tadpole or frog second intermediate host, where it develops to a mesocercariae (infective larval stage and equivalent to metacercaria for other flukes). If a tadpole is infected, the parasite will persist and remain infective through to the adult frog stage. If an infected frog is eaten by a small mammal paratenic host, the mesocercariae can survive in the tissues of the paratenic host and remain infective.

Infection of the carnivore definitive host follows ingestion of an infected frog second intermediate host or a small mammal paratenic host. Following ingestion by the definitive host, the mesocercariae migrate through the abdominal and thoracic cavities and the lungs before returning to the small intestine and completing development to adults. Alaria marcianae, the species in cats has a similar life cycle but can also be transmitted to kittens through the mother’s milk.

Epidemiology

Pathology and clinical signs

Diagnosis

Treatment and control

Control of Alaria species is usually impossible, in essence because of the vigilance required to prevent most dogs, particularly those in rural areas, from eating frogs and small mammals.

Public health significance

Occasionally what appear to be Alaria mesocercariae have been recovered from the eyes of people, including one probable case in Saskatchewan in 2005.